Artifact - Salisbury University

advertisement

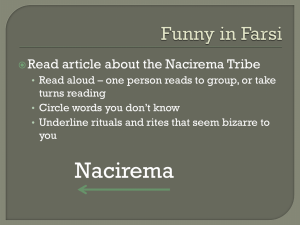

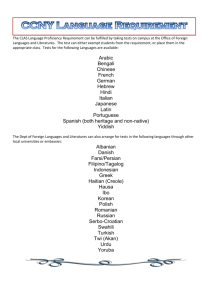

1 Bilingual Person Interviewed: Mahsa Zia Shakeri Interview Sessions: Stephen Decatur Middle School 9815 Seahawk Rd. Berlin, MD 21811 Wednesday, June 15, 2005 from 10:00 – 11:30 Thursday, June 16, 2005 from 11:00 – 12:30 ***Click here to view a PowerPoint Presentation on Mahsa*** Mahsa Zia Shakeri, an eighth grade student at Stephen Decatur Middle School was chosen for my ethnography project because she is the model student. Mahsa demonstrates the level of success one can accomplish, in a short amount of time, with determination, motivation, intelligence, and support. Mahsa has evolved from non-English proficient to fluent-English proficient in three years and will continue to thrive as her thirst for knowledge increases. Mahsa was also chosen to be interviewed for purely, selfish reasons. I was intrigued by Mahsa’s family and her determination. Also, I am not knowledgeable when it comes to Iran and the Muslim religion. I viewed this assignment as an opportunity to expand my horizons and better myself as an individual, as well as a teacher, by learning about an unfamiliar culture and country. I realized the importance of determination, motivation, and family influences both inside the classroom and out. With the continued support from her family, friends, and teachers, I am confident that Mahsa will succeed in all 2 aspects of her life and I am anxious to see how the world will change because of her. Mahsa Zia Shakeri was born on December 13, 1990 in Tehran, Iran. Her parents, Saeed Zia Shakeri and Zahra Mojtabaei, were both ambitious parents and well-educated in their professional fields. Her father worked as a chiropractor, which he continued to pursue upon his arrival in the United States. Her mother was a successful, nurturing mom who continues to attend college to advance her knowledge. Mahsa grew up in Mashhad, Iran learning from, and looking up to, her older sister, Shakila, who has now graduated from high school and is continuing her education at Salisbury University. Although she was born in Tehran, Mahsa spent the first eleven years of her life living in Mashhad, Iran before moving to the quaint town of Berlin, Maryland. There, Mahsa’s father joined her uncle, who worked as a chiropractor. Mahsa’s parents had dreamed of moving to the United States since the birth of their first daughter in 1985, with the hope of providing them with a quality education. Mahsa has begun to realize how lucky she is to have supportive parents who value education. She appreciates the sacrifices they have made in order to provide their daughters with an education and she does not want to disappoint them. Mahsa began her education at Berlin Intermediate School in Berlin, Maryland, on December 14, 2001, one day after her eleventh birthday and two 3 weeks after arriving to the United States, as a linguistic minority. Knowing only two words, dog and apple, she relied on her peers to help her adjust to her new school and way of life. Not only was Mahsa unfamiliar with the language, she was also unfamiliar with the culture. There were many obstacles that needed to be overcome, and differences that needed to be addressed, in order for Mahsa to be successful and acclimate to life in the United States and in school. Mahsa attended a small, all-girls’ school in Iran where she was expected to wear a uniform consisting of a head wrap. Teachers were permitted to hit their students as punishment and assigned numerous hours of rigorous homework each night, especially on weekends. Imagine Mahsa’s surprise when she began school in the United States with co-ed classrooms, no uniform policies, and received only a couple hours of homework each night, minimal considering the expectations in Iran. Besides the cultural differences, Mahsa also had to learn a new alphabet and had to train her eyes to scan text from left to right instead of from right to left. Mahsa’s flexibility and openmindedness helped prepare her for the challenges of learning a new language. According to the inner function of bilingualism, Farsi is Mahsa’s primary language. Although she is currently capable of speaking English fluently, she talks to herself, writes diary entries, curses, and occasionally dreams in Farsi. When Mahsa first began her journey towards learning English, her language deficiency put her at a disadvantage as well as an 4 advantage, when compared to English Language Learners from other cultures. Many English Language Learners in today’s society live in neighborhoods with people from their native-country and attend schools with students who speak the same native-language. It is not as critical for these English learners to integrate in to the culture and learn English because they already have a support group in their native language. Mahsa, however, was unable to communicate or understand anyone outside of her family so she was forced to learn the English language quickly in order to make the transition smoother and more tolerable. Leki says that, “the most powerful factor in determining a learner’s ultimate language achievement…is motivation.” She continues on saying, “the more motivated the learner is, the more likely the learner is to spend time interacting with the target language and the more proficient the learner will become.” Mahsa exemplifies this quote and demonstrates to witnesses that a lot of motivation can go a long way. Surprisingly, Mahsa’s motivation would be considered instrumental, according to Leki. She does not necessarily have a desire to integrate into the English language’s discourse community although she is not completely avoiding it. On the other hand, she has the desire to learn English in order to accomplish some other goal. Mahsa was extremely clear in that she would be returning to Iran after completing college to live and to be a pediatrician or an ophthalmologist. She informed me that learning English in the United States is extremely popular and is key to 5 being successful in Iran. Mahsa was motivated to learn the language for extrinsic, as well as intrinsic, rewards. First of all, research has shown that “people become bilingual because they want to speak the language of power.” In the United States, English is considered the common language of the people, or the language of power. Because of this, Mahsa’s father was highly motivated to learn English. His family’s well-being depended on his ability to provide for them by becoming a successful chiropractor in an English-speaking society and he communicated this importance to his family. In school, English was the language of power for Mahsa also. She wanted to be able to understand and to be aware of lessons and activities in class. She would review assignments each night with a bilingual dictionary in an attempt to construct meaning and to increase English exposure even though she could not understand any of the English words. Aside from school work, Mahsa’s mother encouraged her to memorize fifteen English words each night and then tested her on the words. Socially, Mahsa was starved for friends but needed to learn how to communicate with them. Then there was the issue of her younger cousins. Her uncle’s two sons with an American wife were monolingual in English, so, for Mahsa to communicate with this side of her family, she needed to learn English. Mahsa’s family was also living with her uncle at this time so she was constantly exposed to English even if she wasn’t actively making meaning of the utterances. In the back of her mind, Mahsa 6 was motivated to learn English because she saw it as a means to an end. She knew she would be able to return to Iran and find a good job if she were bilingual in Farsi and English. Because of these factors, Mahsa concluded that it was necessary to learn the English language so she dedicated her free time to activities that would enhance her language learning. Mahsa became involved in hobbies and organizations outside of her comfort zone in order to interact with native English-speaking individuals and to improve her English skills. She took piano lessons with an English teacher and she joined a county field hockey team. She was an extrovert, easily making friends with her native-English speaking peers and trying out the new language, not focusing on the mistakes. Leki thinks that extroversion is related to the ability to generate interaction in the target language, in this case, English. I would consider Mahsa a “High Input Generator” because she would “seek out opportunities to use the target language.” For example, during the summers off, Mahsa would either attend summer school, baby-sit, or volunteer as a counselor at Camp Horizon in West Ocean City. She also took to reading. All of these activities contributed to Mahsa’s English language growth and awareness. The rigorous assignments and high expectations placed on Mahsa while attending school for six years in Iran has influenced her English learning in the United States. Mahsa was accustomed to putting forth her best effort in all 7 she did in Iran. In other words, she had been conditioned, since the first grade, to study for numerous hours and to complete various intellectually demanding assignments each night. In Iran, harsh punishments would prevail for those students who failed to complete their homework assignments. Students would be sent to the office, reprimanded, or slapped for incompletion of assignments or for not understanding information. When Mahsa arrived to the United States and began school, she continued the same rigorous schedule, this time focusing on learning the English language. If she did not receive 4 hours worth of homework, for example, she would study, read, or practice English until she felt it was sufficient. This determination, along with the involvement and pressure from her parents, has prevented Mahsa from falling prey to the ‘laziness’ that lurks inside many of her peers. Mahsa attended school for six years in Mashhad, Iran, learning to read and write in Farsi. When Mahsa arrived to the United States, she was literate in her mother tongue. According to Skutnabb-Kangas Toukomaa’s developmental interdependence hypothesis, students that have “well developed skills in one language will favor the acquisition of good skills in the other.” Because Mahsa was already proficient in her native language of Farsi, she was able to construct meaning from written English. Being literate in Farsi also allowed Mahsa to depend on, and refer to, a bilingual dictionary in the early stages of language learning to act as a reference for English text and 8 to complement lessons. Aside from the benefit of being able to utilize a bilingual dictionary to construct meaning, Mahsa does not believe being literate in Farsi contributed to her rapid acquisition of the English language since the two languages are so diverse. Farsi contains approximately thirtytwo letters to English’s twenty-six. Sentence structure between the two languages also differ, for example, Farsi uses “(S) (PP) (O) V” unless the object is definite and then the sentence structure is, “(S) (O + “r□:”) (PP) V.” In English, however, the most common sentence structure is “(S) (V) (O or PP).” These differences cause problems for most language learners when translating ideas into written English. Although Mahsa is considered bilingual and is able to produce comprehensible written English, it is definitely the most challenging aspect of the English language skills for her. Mahsa has achieved the basic interpersonal communication skills (BICS) and is working towards achieving cognitive academic language proficiency (CALP), if she hasn’t already. Mahsa is capable of effectively communicating with her peers and teachers in a variety of domains. Mahsa may be lacking some BICS since she is not familiar with curse words in English, which could be considered “playground talk.” In my opinion, however, this unfamiliarity displays her character and not her English knowledge. Regarding CALP, Mahsa is successful in her content-area classes and has achieved the Principal’s list for the past two years. 9 According to Romaine, Mahsa is considered a coordinate bilingual since she learned Farsi first, growing up at home in Iran. Years later when Mahsa’s family moved to the United States, she began learning English in a separate environment. The two languages have developed separately from one another and Mahsa has developed a unitary system which operates for both languages. Currently, Mahsa rarely confuses the two languages. She admits that code-switching used to be difficult but she is now comfortable and efficient at switching between English and Farsi. Mahsa attributes this ease to practice. Because Mahsa lived in the United States with four native-Farsi speaking people and three native-English speaking people in the house, she was constantly surrounded by both languages. She also has had practice translating her grandmother’s Farsi words to her English-speaking Aunt. In my opinion, Mahsa’s capability of keeping the two languages separate coordinates with the current theory that the language of incoming information determines which language is used. Mahsa speaks to her family in Farsi because they address her in Farsi. In school, however, Mahsa uses English because she is addressed in English. Mahsa did share one story with me where she was talking to her grandma in Farsi and switched to English without realizing it. Through practice, Mahsa has learned to control the “switch” when using Farsi and English. 10 Mahsa’s growth and achievement is an exception to that of the typical English language learners in this society. It is my belief that those students, such as Mahsa, who are motivated to learn English, are already literate in their native-language, are intelligent individuals, and have supportive parents will be successful in acquiring a new language. For these students, bilingual education would act as a crutch, not used as a tool. Mahsa’s success stems from the fact that it was necessary to learn English and she had access to the resources to be successful. Mahsa was also able to rely on her American aunt for reinforcement and reassurance. On the other hand, many English language learners come to the United States and are not literate in their native language. Remember, that according to Skutnabb-Kangas Toukomaa’s developmental interdependence hypothesis, students that have “well developed skills in one language will favor the acquisition of good skills in the other.” For those students who are not literate in their native language, a bilingual program would be beneficial, if not necessary; because in order to construct meaning in the second language, the student needs to be proficient in the native-language. Also, many of these students do not have the resources or the time to devote to learning, or teaching themselves, another language. For this population, a bilingual education program would be beneficial. ***Click here to view a PowerPoint Presentation on Mahsa***