donkey power

advertisement

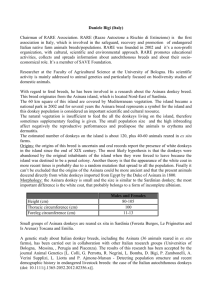

Peta Jones: Why donkeys should work Page 1 of 9 PAPER PREPARED FOR REGIONAL WORKSHOP ON ANIMAL WELFARE, 24TH TO 28TH SEPTEMBER 2007 - NAIROBI, KENYA (NOTE: NO ILLUSTRATIONS ARE PROVIDED HEREWITH. MANY WILL BE USED IN AN ACCOMPANYING POWERPOINT PRESENTATION, AND MAY BE SELECTED FROM THAT.) Published later without any pictures as: Jones, P.A. 2008. Why donkeys should work. 49-53 in F. Ochieng & A. Wanja (eds). Animal welfare, livelihoods and environment (Report of 1st Regional Workshop, Nairobi, August 2007). Nairobi: Animal Welfare Action Kenya (AWAKE) and Animal Traction Network for Eastern and Southern Africa (ATNESA). [PDF document] WHY DONKEYS SHOULD WORK Peta A. Jones, MSc, PhD Donkey Power Facilitation and Consultancy, PO BOX 414, TSHITANDANI/MAKHADO 0920, South Africa (e-mail: asstute@lantic.net) ABSTRACT Working donkeys are not necessarily abused donkeys. Work can benefit donkeys in many ways, and three main areas of benefit are described here: the effect on donkey behaviour, the health and condition of donkeys, and the value of donkeys. Each of these are enhanced when a donkey works, as long as care is taken that abuse is not deliberately inflicted or is the result of careless or ignorant management. It is the human factor not the work factor that can have a bad effect. INTRODUCTION Working donkeys, where they are observed, most often suffer from three main things: Wounds – due to poor harnessing and hitching, or otherwise abuse by owners. Ingestion of inappropriate things, such as plastic and sand. Parasite infestation (where this may be detectable, such as in the faeces). All these are problems of management, not of work. At the first Colloquium on Working Equines in Edinburgh in 1990, I clearly remember that it was said to me (by someone of much my age and type) that working donkeys leads to their abuse. Since my acquaintance with donkeys began because I needed them to work for me, this has worried me ever since. I said at the time that use was not necessarily abuse, and of course that is still true, but over the years I have come to see that there are much more positive things to be said in favour of putting donkeys to work. I have also learned to see that – The abuse of animals takes place independent of whether or not they are working animals. Animal abusers are also most likely to be abusers of people (and vice versa), thus deliberately cruel. Where donkeys are concerned, much of the abuse nonetheless arises from ignorance rather than deliberate cruelty. Ignorance regarding donkeys is widespread and has much to do with socioeconomic stratification. 1 Peta Jones: Why donkeys should work Page 2 of 9 What follows here, therefore, puts aside the matter of human variability in the matter – some of which I have dealt with in detail elsewhere (e.g. Jones 1991; 2000; 2004a; 2004b) – and concentrates mainly on the donkey’s own response to work. BEHAVIOUR Once one recognizes that a donkey is an unually intelligent animal (everything I have read about dolphin intelligence could easily be duplicated by donkeys), one readily sees how a donkey applies its intelligence. Start digging a hole or setting up an instrument in a field where there are donkeys, and in no time they will have gathered around to investigate. They are endlessly interested in what humans do, and a grazing herd will generally have one member on the watch for human activity. One of the observed differences between horses and donkeys is that horses are performers and donkeys are workers. From this it can be inferred that donkeys prefer to have a sense of purpose in what they do. Without anything to do but eat, donkeys can suffer from boredom. I have seen this in my own donkeys, who are supposed to be rotated in their cart pulling duties, but unless I am watchful, the same pair get used every time. I realize this has happened when other donkeys start behaving in a lethargic manner: those are the ones that have not been worked regularly, and it is possible that they are sulking because they feel others have been favoured. As soon as they have been used for some work, this changes. It should also be mentioned that intact stallions are more likely to break out of any confinement, and will travel long distances in search of jennies on heat. If they are working regularly, they are less likely to do this. However, castration must be seriously considered for donkeys, if only to prevent them doing themselves damage inadvertently and other donkeys deliberately (Jones 2003). Donkeys in general, however, show a distinct liking for travel. They easily adopt routines, like coming home in the evening, but they give very little trouble on long journeys away from home, quickly learning who is in charge and adapting their movements to the whereabouts of that person, and the whereabouts of each other. In any group of donkeys, there is usually a leader that the others will confidently follow in single file along the path, including up and down steep rocks with loads on their backs. It is small wonder that donkeys have been used as transport animals since they were first domesticated, more than 6000 years ago (Camac 1997; Gebreab et al. 2004). Part of a donkey’s taste for travel arises, of course, from its eating habits. Donkeys relish a varied diet, but are at the same time fairly fussy about what they eat. They will eat not only leaves, but fruit, seeds, twigs, roots and bark. But not just any leaf, fruit, twig, root or bark; they learn what is available at different times of year, and seek out what they want and like best. They are willing to range long distances to find just the taste, just the succulence that they have decided upon. From this probably arises their amazing ability to remember paths and routes. So they are not only temperamentally well suited to travelling, travel is probably something that they positively need. 2 Peta Jones: Why donkeys should work Page 3 of 9 A donkey is not a stubborn animal: it simply and usually justifiably thinks it knows better than human beings what circumstances will suit it best. I am one of those who, if finding myself lost when travelling with a donkey, will let the donkey lead me home instead of trying to force it down a path that I may think is the right one but the donkey knows is not. A donkey deprived of travel will do its best to contrive an opportunity. An ordinary fence or gate will not stop a donkey for long. In South Africa a common form of fence is five-strands of barbed wire. I have observed donkeys climbing through such a one, lifting one to crawl under it and jumping over one – all without damage. When really excited one donkey actually pushed a fence down, which tore its skin but did not seem to bother it. As for gates: they must be large and stout and padlocked – all three – to keep a donkey in. Regular opportunities to travel outside the fences and gates which confine it, therefore, reduce a donkey’s tendency to find ways through them. In the days when I used to take my donkeys shopping, they only had to see me with the bags and ropes in my arms to line up at the gate, ears upright in happy anticipation. They loved shopping particularly, being greeted by people and having intresting things happen around them. And I have to say that they particularly desired opportunities to explore the rubbish dumps outside the shops... Regular work of all kinds can have a positive effect on donkey behaviour, but often this is more of a reflection of the animal’s health and condition. Any animal in poor health and condition will give trouble when it works, and behaviour and condition are not always easy to separate. HEALTH AND CONDITION Not only for donkeys, but it is true for most animals, including human, that regular exercise is necessary to overall health. It could of course be argued that donkeys will remain exercised even if they do not work: the wide foraging that they do for food alone ensures that. But does it ? One needs only to look at donkeys that are kept solely as pets, or in a caring sanctuary such as the Donkey Sanctuary in the UK, to see how easily donkeys can become obese. To be sure, such donkeys are not given much opportunity for movement, and do not need to forage, but they could be seen as illustrating the adverse effects of idleness in donkeys. Overwork of course should be avoided. What is overwork for donkeys ? We have figures for donkey work: 1.8-2.8 megajoules per day; power output 170-200 Watts; ~ 250 newtons for 4 hours; forward movement ~ 0.7 metres/second, loads 80-100 kg, pulling 400-500 kg on the level reduced to 200-250 kg on a 6% gradient, work not more than 6 hours a day, etc.etc., much of which is never going to be measured by a donkey user. In any case, time and effort need to be balanced: a lot of effort can be exerted effectively over a short time, but over a longer time less effort will be more efficient (Beltzer & Kutsbach 1991; Smith et al 1994; Tiwari et al. 2004). We know this in the work that we do ourselves, and it is just as true for donkeys. People often 3 Peta Jones: Why donkeys should work Page 4 of 9 ask me how overwork can be judged, and I always say: “When the donkey sits down and refuses to move, then it has worked enough.” Then, of course, the trick is to be able to predict when the donkey will do this, and avoid it happening. I can only draw on my own experience in this. I have had a donkey sit down after only two hours of carrying no more than 20 kg, which would be difficult to describe as overwork. However, at the time she had not done any work for fully a year, during which time she had also given birth to a foal which she was still suckling, so from her point of view carrying 20 kg for that long was definitely overwork. To put it simply: she was out of condition. Regular work is necessary to keep a working animal in condition, not least for work itself. In some of the parts of Africa that I know, where donkeys may be a rather unfamiliar technology, adopted not for transport but for plowing, and still confused with oxen, donkeys are neglected for most of the year, and only rounded up when the rains begin and some intense plowing is required. In such circumstances the work can be excessively hard and painful for donkeys, which would otherwise handle it easily. General condition also benefits from work. Four years ago, when my donkeys had been in a new environment for two years and were still apparently having health problems, I agreed to let them spend a season ploughing for some neighbours further up the mountain. Naturally I was nervous about it, with one of the donkeys having been blinded by a snake eighteen months earlier, and none of them in top condition since they did not seem to be eating much of the vegetation available to them, I made regular visits to their new locality, and supervised much of their work myself. By the time I had satisfied myself, after about a month, that all was well, the rains had got so heavy that I could no longer take a car up there, and I stopped checking, only arriving to fetch my little herd when the dry season began. Much to my surprise, they were looking healthier than they had in years, as well as behaving in the disciplined and coordinated way typical of well-trained donkeys. They also seemed to be eating a greater range of the vegetation – as they have been ever since. In fact, that season of ploughing turned the corner for them health-wise. They work for me more regularly now, but are suffering far fewer health problems, and the blind one, although still blind, is perfectly at ease now, not just working but moving with the others on rocky slopes and through the bush. These may be just case studies, anecdotal examples, but they agree with what we can deduce from what we know of mammals in general: they thrive best when fulfilling the functions for which they were bred or evolved. And the function of donkeys is work. They know it as well as we do. VALUE Not only to themselves, but also to most humans, it is work that gives donkeys their value. The difficulty here is that humans are generally reluctant to put a value on work. A good example is the low valuation that is put on the work of women, as compared to that of men. Centuries of slavery, also, have not helped, and of course donkeys – like most animals – are still regarded as not much different to slaves. 4 Peta Jones: Why donkeys should work Page 5 of 9 We can take reassurance from the fact that this is gradually changing, for women and men at least. For donkeys the transformation will probably come not so much from the work they do, but through what that work can provide. Two things that immediately come to mind are water and tourism. In both cases the donkey actually provides transport, but something of significance is added. To take water first: we are all becoming aware of its crucial importance at a time when its supply can no longer be taken for granted. Ten whole years ago South Africa produced a ‘Save water’ stamp which featured a donkey cart – even though the hitching system was nothing that could benefit a donkey (Jones 1999). Ten years on, donkeys are still playing this essential role in rural areas in South Africa – and how much more in Zimbabwe ? – to the extent that a colleague has been able to determine charges, as follows: Table 1: Charges for transport of goods by donkeys in Limpopo Province (Khodobo 2006) GOODS TRANSPORTATION / WORK 80 kg Mealies [i.e. maize] 50 kg Cement Wood and Sand Water DISTANCE 5-6 km 5-6 km 10 km 10 km PRICES PER LOAD R 8.00 R 5.00 R35.00 R15.00 This table is somewhat incomplete in what it tells us. It is worth noting that other enquiries in the same area in the same time-period have yielded additional figures: water in a 200-litre drum will cost R20.00, and in a 25-litre plastic jerrycan, R2.00 – although I don’t quite know why the latter should be cheaper. It is also not clear if these prices include transport, and, if so, for what distance. It could be argued that, at R15.00 for 10 km, a transporter is under-charging. In 2002 it was calculated, using South African prices, that using a donkey cart cost a donkey owner R25.40 to transport 500 kg 30 km. (Naudé-Moseley & Jones 2002). The cost does not really vary with the mass of the load; time and distance are the operators here. It can be expected, therefore, that these prices will slowly rise, especially as the cost of donkeys is currently rising due to the increasing demand for them. The fact that this increase in demand results from an increase in the demand for their work is of course also significant. Tourism, on the other hand, is as yet unexplored as a potential for donkeys. Here and there it is already happening in South Africa (e.g. Campbell 2005), although to my surprise it seems to assume almost exclusively the use of donkey carts. Having lived in steep rocky areas myself, I am much more inclined to regard donkeys as the perfect foot-safari companion, and have made the following arguments to our local developers: Local tourism bodies would do well to think of using donkeys to provide tourist transport and access to remote areas. If initiated at an early stage of tourism development of the area, this will ensure that less damage is done to the environment than if motor vehicle access and transport were provided. It has already been found in other parts of the world that donkeys themselves constitute something of a tourist all prices here given in South African rands (R or ZAR). 5 Peta Jones: Why donkeys should work Page 6 of 9 attraction, as they are increasingly less known in urban environments, and yet are so very ‘user friendly’. Many keen explorers of wildlife are in their maturer years and, while capable of walking and even climbing fair distances, do not necessarily have the stamina to carry on their backs all that is required for their nourishment and comfort, or alternatively to do without such nourishment and comfort. With donkeys, such problems not only fall away, but companionship is provided which is not that of fellow and possibly irritating humans, but a creature for whom wild mountain, bush and track, is a natural habitat, and yet is not a wild animal but one tolerant of and well used to human ways. See also the attached ‘Position Paper’ drawn up some years ago. Where tourism is concerned, especially in Africa, donkeys also compare very favourably to horses. I can provide a list if anyone is interested ! Although being a tourism provider may be costly, it also brings substantial returns, and is becoming an income generator of choice in many rural areas of developing countries. The fact that including donkeys can be a positive draw card, and at the same time be so positively ‘green’, gives donkeys themselves a stake in a new avenue to prosperity. And note this: tourists do not like to see sick or ill-treated animals. If an owner expects to use a donkey in the presence of tourists, that donkey had better be treated well, or business will not be sustainable. It is not only value that will be enhanced by tourism, but welfare as well. In fact, I would argue that value and welfare cannot be easily separated. As the value of an animal increases, so does concern for its welfare. Who wants to lose an animal that is worth a fair bit of money ? This is why, in all the workshops I run, I place strong emphasis on the costs and returns of owning a donkey, demonstrating conclusively that the returns – whether in earnings or savings – can substantially outweigh the costs. Until this is recognized, the value of the work that donkeys do may be difficult for an owner to see. CONCLUSIONS The welfare of donkeys is closely connected to the work they do. As long as this work is well managed and avoids deliberate abuse, a donkey will benefit in a number of ways. Its behaviour will stabilize with no bad effects on its temperatment, and optimum health and condition will be maintained. The management of donkey work, therefore, needs to be well informed. An owner needs to know the needs and capacity of each individual donkey, and to use equipment and systems that do not cause wounding and discomfort. Such equipment and systems are not expensive, and are easily within reach of rural donkey owners who can make much of it themselves. REFERENCES Betzer, J. & H.-D. Kutzbach, 1991. The role of donkeys in agricultural mechanization in Niger – potential and limitations. 223-230 105 in D. Fielding & R.A. Pearson (eds), Donkeys, mules and horses in tropical agricultural development (Colloquium Proceedings). Edinburgh: University. ISBN 0-907146066 6 Peta Jones: Why donkeys should work Page 7 of 9 Camac, R.O., 1997. Introduction and origins of the donkey. 9-18 in E.D. Svendsen (ed), The professional handbook of the donkey (3rd edn). London: Whittet Books. ISBN 1-873580-37-1 Campbell, C., 2005. Artists wins hearts for Karoo donkeys. Cape Argus, 1 November: 13 Gebreab, F., A.Gebre Wold, F. Kelemu, A. Ibro & K. Yilma, 2004. Donkey utilization and management in Ethiopia. In Starkey, P. & D. Fielding (eds). Donkeys, people and development. A resource book of the Animal Traction Network for Eastern and Southern Africa (ATNESA). ACP-EU Technical Centre for Agricultural and Rural Cooperation (CTA), Wageningen, The Netherlands. ISBN 92-9081-219-2. Jones, P.A. 1991. Overcoming ignorance about donkeys in Zimbabwe – a case study. 311-318 in D. Fielding & R.A. Pearson (eds), Donkeys, mules and horses in tropical agricultural development (Colloquium Proceedings). Edinburgh: University. ISBN 0-907146066 Jones, P.A., 1999. Donkey power: reinventing the wheel ? This new animal, the water donkey. The Veteran Farmer, 16: 20-21 Jones, P.A., 2000. Hitching is the problem with harnessing donkeys. 185-192, in P.G. Kaumbutho, R.A. Pearson and T.E. Simalenga (eds), 2000. Empowering farmers with animal traction (Workshop proceedings, Mpumulanga, South Africa, September 1999). Harare: Animal Traction Network for Eastern and Southern Africa. ISBN 0-907149-10-4 Jones, P.A., 2003. Must castration be selection ? The case of donkeys. 149-152 in D. Vilakati, C. Morupisi, L. Setshwaelo, C. Wollny, A. von Lossau & A. Drews (eds) Community-based management of animal genetic resources (Workshop Proceedings). Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Jones, P.A., 2004a. Donkey power in Mozambique. Draught Animal News, 41:29-31 Jones, P.A., 2004b. Response to demand: meeting farmers’ needs for donkeys in southern Africa. 196202 in D. Fielding & P. Starkey (eds), Donkeys, people and development. A resource book of the Animal Traction Network for Eastern and Southern Africa (ATNESA). Technical Centre for Agricultural and Rural Cooperation (CTA), Wageningen, The Netherlands. ISBN 92-9081-219-2 Khodobo, A.L., 2006. Assignment of trainee inspector for the National Council of SPCAs (Unpublished typescript). Louis Trichardt/Makhado SPCA. Naudé-Moseley, B. & P.A. Jones, 2002. Donkeys don’t need roads. Farmer’s Weekly, 92046/Grow 131 (22 November): 4. Smith, D.G., A. Nahius & R.F. Archibald, 1994. A comparison of the energy requirements for work in donkeys, ponies and cattle. 17-22 in Bakkoury, M & R.A. Prentis (eds), 1994. Working equines (colloquium proceedings). Rabat: Actes Editions. ISBN 9981-801-11-9 Tiwari, G.S., R.N. Verma, R. Garg, H. Shrimali & J.L. Chaudhary, 2004. Tractive efforts of various draught animals in Indian conditions. Draught Animal News, 41:36-39 7 Peta Jones: Why donkeys should work Page 8 of 9 APPENDIX POSITION PAPER ON DONKEYS IN SOUTH AFRICAN TOURISM The tourists Those who are rich enough to afford travel, particularly overseas travel, are not necessarily the young, although they may be adventurous. It follows, therefore, that they may not have the stamina for long walks through alien environments in the heat, however willing they may be. Such people are usually educated, rather more than most South Africans are, and have an informed awareness of environmental and global issues. Tourists of this kind are very often sophisticated enough not to feel any need to roar around in powerful vehicles, churning up delicate soils and microorganisms and frightening small animals. Tourists would be coming to Africa to experience ways of life no longer obtainable in their own countries. This would include exploration of cultures which are close to nature and the rhythms of the earth and seasons. Contact with indigenous peoples is therefore important to them. Because most tourists come from urban environments, they find it enlightening to have contact with animals which are intelligent while not being merely pets. Donkeys are animals which can be both ridden and loaded without difficulty due to their obliging nature and convenient size. When loaded or ridden, donkeys move more smoothly than any other riding animal (except the mule), and maintain a steady walking pace matching the human one; they undertake bursts of high speed only with reluctance and never for long distances. Tourists value companionship which is not that of fellow and possibly irritating humans, but that of a creature for whom wild mountain, bush and track, is a natural habitat. Not many urban (or even rural) people are aware of the wild nature of many types of animal, and often make dangerous mistakes in their approach to and treatment of the animals they contact. So it is important that the animals which they actually handle rather than just view should be animals that are tolerant of human ways, and also are of a size that even fairly weak and nervous humans can easily manage. For people who are disabled in some way, the assistance of a working animal can be important. Even for the mentally disabled, in many countries donkeys and other small equines have been found to be very useful in therapy. Donkeys can therefore open up tourism to the disabled. The local people The use of donkeys allows the participation of local people in the exploitation of their own environment for tourism purposes, since it is local people who are the most accessible donkey owners. It also gives an opportunity for locals to accustom themselves to contact with tourists in a setting where they are the experts, not the tourists – a more healthy relationship than simply being a servant. Donkeys are more democratic animals, since, however poor rural Africans may seem, there is some class distinction, in that people who possess cattle are accounted rich. Of course such people often also own donkeys (knowing that they 8 Peta Jones: Why donkeys should work Page 9 of 9 are more efficient workers), while the poorest do not. In between are the ‘middleincome’ group who may own donkeys but not cattle. Donkeys are more gender-sensitive, since fewer taboos are associated with donkeys, which are often also owned and managed by women. The environment Not all domestic animals – let alone wild animals – have the same impact on the environment. Ruminants emit a greenhouse gas (methane). Large animals compact delicate soils and/or churn up much dust, almost as much as motor vehicles. Large animals also have large appetites to satisfy. Both cattle and horses are large eaters of high-quality grasses, leaving little for other species. Donkeys are neither ruminants nor large animals. One donkey eats about one-fifth of the amount eaten by an ox of equivalent size, and one twelfth of the protein. This is because donkeys are among the most energy-efficient of domestic animals. They eat a large variety of vegetation types, little though often, and will travel long distances to find their food, so not exhausting one environment. Also not being ruminants, they emit no particularly dangerous gases. While having nearly the strength of oxen, donkeys are much lighter for their size, and have much smaller hoofs – which, being round, do less damage that the pointed halves of cloven feet. And of course donkeys are much lighter and smaller than heavily-muscled horses. Relationship with southern Africa and its wild animals Donkeys are direct descendants of a wild equine that was the equivalent of and until recently occupied the ecological niche of a zebra in the north-east corner of Africa. Donkeys are therefore very well adapted to the hot, dry environments of Africa They suffer very few of the diseases of exotic animals, sharing the resistances of wild animals. Donkeys are more likely to be carriers of the diseases of the African wild than suffering from them. More than other domestic animals, especially the herbivores, donkeys have awareness of and responses to danger which are highly sensitive and very like those of zebras: they freeze into watchfulness and, although they can move fast, never gallop very long distances. Thus, in the African environments, donkeys are safer than most other domestic animals. DONKEY POWER FACILITATION AND CONSULTANCY Peta A. Jones, MSc, PhD P.O. Box 414, MAKHADO/TSHITANDANI 0920, South Africa +27 cell [0]83 686 7539 tel & fax [0]15 517 7011 e-mail asstute@lantic.net 9