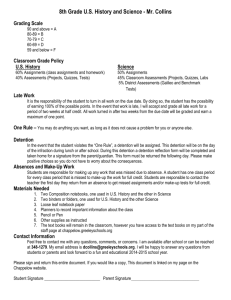

Detention Facility Conditions and Standards

advertisement