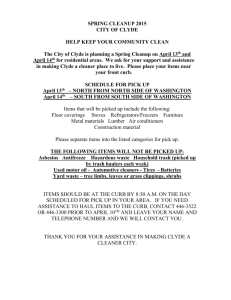

View as DOC - Lerch, Early & Brewer

advertisement

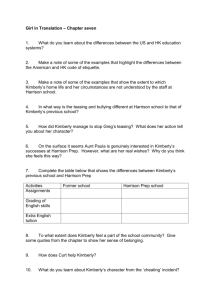

CURRENT TAX DEVELOPMENTS – Estate Planning Journal, November 2007 Estate of Special Needs Child Can Deduct Loan From Parent Estate of Hicks, TCM 2007-182 Author: FRANK S. BALDINO FRANK S. BALDINO is a principal in the law firm of Lerch, Early & Brewer, Chtd. in Bethesda, Maryland. In Estate of Hicks, 1 the Tax Court permitted the estate of a special needs child to deduct a loan made by the parent to a non-special needs trust established for the benefit of such child as part of a transaction designed to preserve the future eligibility of the child for Medicaid. Facts Kimberly Hicks was approximately three years old when the automobile in which she was a passenger and which her mother was driving collided with a train. The accident left Kimberly a quadriplegic, dependent on a ventilator to breathe, and in need of constant medical attention for the rest of her life. Kimberly's father, Clyde, sued the railroad. The local probate court appointed a guardian to represent Kimberly's interests in the suit. The suit sought damages for medical expenses, pain and suffering, and Clyde's loss of consortium from Kimberly. State (Ohio) law provided that parents had a legal obligation to support their minor child using the parents' property. While it was difficult to estimate Kimberly's life expectancy, one report prepared at the request of Clyde's attorney suggested that Kimberly would live into adulthood, which meant that Clyde's statutory duty to support Kimberly would last until she reached the age of majority. At the time of the accident, the Hickses had very good medical insurance which paid for almost all of Kimberly's medical expenses and had no lifetime cap. However, the Hickses would lose this coverage if they no longer worked for their employer, or if their employer changed insurers, or if the insurer changed the terms of the medical insurance policy. These concerns made it very important that Kimberly be in a position to qualify for Medicaid when she became an adult or if the Hickses lost their medical insurance. To qualify for Medicaid, however, Kimberly would have to spend down the portion of any settlement from the suit allocated to her. After the railroad agreed to settle the suit for a lump-sum payment, the Hickses' lawyer suggested that they create two trusts for Kimberly. The first trust was the Kimberly Hicks Special Needs Trust. This trust was designed to comply with the Medicaid eligibility rules applicable to trusts. Accordingly, although the assets of the trust would not need to be spent down in order for Kimberly to qualify for Medicaid, upon Kimberly's death the remaining assets of the trust would be required to be used to reimburse the state for medical expenses paid on Kimberly's behalf. One million dollars of the settlement was paid to this trust. 753744.1 08252.001 The second trust was the Kimberly Hicks Settlement Fund Management Trust (“the Management Trust”). The assets of this trust would be counted in determining Kimberly's eligibility for Medicaid; $450,000 of the settlement was to be paid to this trust. The Hickses' attorney also suggested that Clyde loan to this trust $1 million of the settlement proceeds that were allocated to him. The loan was evidenced by a promissory note that required the payment of interest but did not require the payment of principal. The note was callable by Clyde upon the occurrence of two events—Kimberly's death or her inability to obtain medical insurance at a reasonable premium once she reached age 18. This proposed settlement required the approval of the local probate court. The proposed arrangement, including the allocation of the settlement proceeds between Kimberly and Clyde, and the loan from Clyde to the Management Trust, was approved by the probate court. Kimberly lived for approximately four and one-half years after the settlement was approved by the probate court. After the approval of the settlement, the Management Trust paid interest to Clyde, which he reported on his income tax return each year. Following Kimberly's death, an estate tax return was filed which listed the total amount of assets in both trusts and claimed the $1 million loan from Clyde as a deductible debt. Analysis The IRS challenged the loan on two grounds. First, the IRS argued that the loan was not bona fide because Clyde never had control or possession over the $1 million since pursuant to the terms of the order of the probate court, the $1 million was transferred directly from the guardian's interim bank account to the Management Trust. The Tax Court rejected the IRS's argument because Ohio law required the probate court to approve any settlement agreed to by a minor's guardian before the settlement could take effect. The Tax Court therefore concluded that the $1 million belonged to Clyde because that is whom the probate court allocated it to in spite of the fact that Clyde never had actual control or possession of the $1 million. The IRS's second argument was that the allocation of the $1 million to Clyde was a sham since Clyde proposed the allocation and Kimberly and Clyde did not have adverse interests with respect to how the settlement proceeds were to be allocated. The IRS contended that because the allocation to Clyde was a sham, the allocation should be ignored and the $1 million should be considered for tax purposes as belonging to Kimberly at all times. The Tax Court rejected the IRS's argument. The court noted that the loan created an income stream in favor of Clyde which was capable of valuation and thus, it was erroneous as a matter of economics for the IRS to contend that the loan was valueless. The Tax Court found that the fact that the loan had value meant that the initial allocation of the $1 million by the probate court to Clyde could not be ignored. In addition, if Clyde predeceased Kimberly, the present value of the note would be part of Clyde's taxable estate. These facts led the Tax Court to conclude that there was real economic substance to the loan. The court also found that since Kimberly was in no danger of imminent death at the time of the allocation, the loan was not an attempt to dodge the imminent imposition of the estate tax. 753744.1 2 08252.001 In addition to economic substance, the Tax Court noted that there were other factors that supported upholding the allocation of the settlement made by the probate court. First, the Tax Court found that a state has an interest in considering the impact of allocations in personal injury cases on the state's Medicaid system. Second, the allocation of the settlement in this case was not between taxable and non-taxable amounts, and therefore the Tax Court believed that it was less likely that tax avoidance was the primary motivation for the allocation. The court found that there was ample justification for a large portion of the settlement to be allocated to Clyde. Under Ohio law, parents have a statutory obligation to provide support for their children. The court determined that given Clyde's obligation to support Kimberly until she was an adult, and in light of the fact that Kimberly's care was enormously expensive, it was reasonable for Clyde to receive a significant portion of the settlement. The Tax Court also concluded that the allocation to Clyde combined with the loan from Clyde to the Management Trust was a reasonable attempt to address several real issues that the Hickses faced. For example, if the Hickses ever lost their medical insurance, it would be desirable for Kimberly to be in a position to qualify for Medicaid as quickly as possible and at the same time have the family be in a position to retain as much of the settlement as possible in order to pay for those expenses not covered by Medicaid. However, if Clyde retained all the settlement allocated to him, those funds would be available to Clyde's unforeseen future creditors. The loan arrangement permitted the settlement proceeds that were allocated to Clyde to be transferred so as to be out of the reach of Clyde's unforeseen future creditors but, based on the repayment term of the note, those proceeds could be transferred back to Clyde if Kimberly needed to apply for Medicaid. Comments This case should be required reading for any attorney advising a family with respect to a personal injury suit and the structure of a settlement. Hicks is more than an estate tax case of interest solely to estate planners. If this technique is ultimately accepted by the Medicaid authorities, it will be very helpful in enabling families to navigate a course of preserving Medicaid eligibility and at the same time making a significant portion of the settlement available for the benefit of the disabled individual. 1. TC Memo 2007-182, RIA TC Memo ¶2007-182 753744.1 3 08252.001