The End of Progressivity

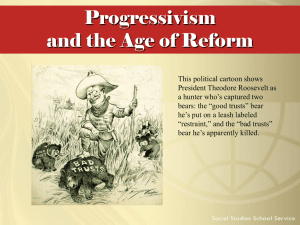

advertisement