From Oracle Bones and Tortoise Shells to Written Expression: The

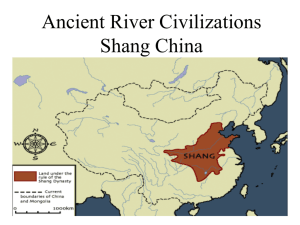

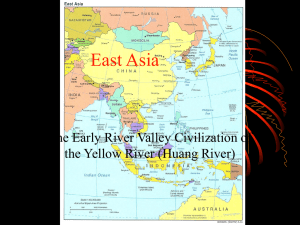

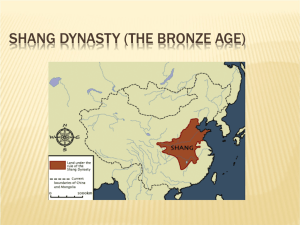

advertisement

1 From Oracle Bones and Tortoise Shells to Written Expression: The Development of The Chinese Written Language as an Ideal Medium for Poetic Expression. Robert E. Kibler 18 September 2003 As we all know, the human story of virtually every culture begins somewhere in the shadowy world of myth and legend. The ancient Greeks, for example saw their world born out of chaos and the transformational and concupiscent nature of the Gods. The ancient Romans were lineal descendents of the mythological boys, Romulus and Remus, raised by a she-wolf. In 16th century Europe the English Tudors similarly traced their lineage back to a group of ancient Trojans who presumably escaped the Greeks two thousand or so years earlier. And on the other side of the planet, the quasi-historical Shang Dyasty of ancient China began, so the Bamboo Annals tell us, when the mother of the first king of the Shang went to take a bath and saw a black bird drop an egg. She ate the egg and became impregnated, eventually giving birth to Hsieh, first of the legendary Shang kings. Yet in China, in particular, the shadow line separating the world of ancient myth from the world of history keeps changing, for the deeper archaeologists dig into the earth, the older Chinese historical time becomes. What was once legendary turns into part of the historical record. Of the three ancient dynasties, for example, the Chou, the Shang, and the Hsia, the preponderance of evidence for their actual existence pretty much ended with the Chou, youngest of the three dynasties. The Chou ruled China from 1122 BCE to 255 BCE, having taken over from the Shang, which ruled from 1766 BCE to 1122 BCE, having risen to prominence while the Hsia faded.i Yet even by the time Confucius began 2 to compile the histories and cultural records of ancient China during the 6th century B.C.E., he lamented that he could describe the ceremonies and court rituals of the Shang, but his descriptions could not be validated through historical record.ii Likewise, when the famous Han Dynasty scholar Ssu-ma Ch’ien began compiling the Shih chi, or Historical Annals, in the 1st century B.C.E., his chapter on the Shang of necessity remained just a bare outline. According to the modern sinologist Kwang-Chih Chang, Ssu-ma Ch’ien had only five reference books related to the Shang at his disposal—and of course, he had nothing on the mysterious Hsia. In our own century, however, all of this has dramatically changed as a result of the discovery of oracle bones and tortoise shells outside the city of An-yang, final capital of the Shang dynasty. These bones and shells were used by the Shang to divine the future, and contain a vast written record of a period of time existing beyond the pale of historical record. Their discovery has opened up a giant doorway not only into the unknown past world of the Shang and perhaps the Hsia, but also into the related world of early Chinese writing. Oracle bones and tortoise shells were used by the ancient Chinese to predict the future course of events. The scapula or shoulder blades of cattle and water buffalo, as well as the plastrons, or under-plates of tortoise shells, were the means by which the kings, emperors, and members of the royal family conversed with and sought the aid of their ancestors. These bones and shells were sanded and polished until their surfaces were made perfect, then questions were inscribed or etched onto the surface of bone or shell. The inscribed bone or shell was then passed through open flames by a diviner, until it cracked. The nature and character of these cracks was interpreted and the future presumably made known. 3 According to Benjamin Schwartz, scapulamancy and plastronmancy probably began among the Chinese inhabitants of the neo-lithic period (8000-2000 B.C.E.), long before the period of the Shang. However, almost all of the surviving fragments of bone and shell associated with the Shang come from the 150 year period of the last nine Shang kings, circa 1200 to 1040 BCE.iii These 33,500 pieces of oracle bone and shell were excavated from an archaeological dig outside of the city of Anyang, beginning in 1928.iv Archaeologists discovered the site after a small child took them to where he had found several of what for centuries had been referred to as “dragon bones—little bits of bone with writing on them.”v What a find--yet it is interesting to note that scholars and archaeologists had paid no attention to these dragon bones for centuries. Indeed, dragon bones, as they were called, were for centuries collected as trinkets and used as a powerful ingredient in Chinese traditional medicine.vi They were discovered to be something other than medicine when in 1899, a Beijing scholar named Wang Yi-Jung was taking a traditional medical prescription of dragon bones for malaria. His houseguest, another scholar and novelist, Liu Eh, noticed inscriptions on the fragments of bones. The two men were astonished, and after a considerable number of years they convinced archaeologists of the Academia Sinica to begin following the trail of these bones. One trail led them to a place just outside of Beijing, where they incidentally discovered the bones of the 400,000 year old Peking Man. Another took them to the city of Anyang and to the young boy who brought them to what looked like a big pile of sand. What they uncovered there in Anyang was unimaginable--an entire Shang palace city, ranging on both sides of the Huan river. 4 Excavators found royal palaces surrounded by temples, underground workshops for casting bronze and molten metals, royal cemeteries full of the skeletons and skulls of sacrificial victims, and pits full of thousands more encircling the palaces. There were underground dwellings and storage pits with stairways and ramps connecting them and going up and down, with complex drainage systems to keep them dry. And there were also underground archival chambers—the first libraries-- full of oracle bones and tortoise shells bearing written inscriptions that would help bring the Shang world to light.vii One of the richest finds came to archaeologists in 1975-76, when they unearthed what is referred to as “Tomb Number 5” containing 80 pits, a dozen tombs, a dozen foundations, and scores of bronze vessels. The chief tomb belonged to Lady Hao, one of the Shang Emperor Wu Ting’s 64 wives, and the subject of many of his oracle bone inscriptions inquiring about her illnesses, child births, and general well being.viii Her tomb had remained unplundered, and 16 sacrificial victims surrounded or were piled upon her grave.ix The overall compound contained granaries, weapon stores, storage for oracle bones and musical stones. In one storage pit, tens of thousands of oracle bone fragments and more than three-hundred whole turtle plastrons were found in a storage area capable of holding 1, 179 turtle shells.x What Lady Hao’s tomb and the other excavated sites did was fill in the generally blank picture of Shang life. Shang society was highly literate, and organized according to clan and kinship ties. Its people knew how to build with tamped earth, and had an advanced understanding of ceramics and bronze tool-making. They fought and hunted with horses and chariots. They were highly superstitious, and believed that gods and spirits controlled all actions. They sacrificed lavishly to their ancestors on a regular basis, 5 and as Kwang-Chih Chang notes, did so according to a neatly organized ritual schedule.xi These sacrifices were often human, and indeed, all of the 1,178 skeletons found at Anyang were those of sacrificial victims,xii sometimes buried alive, or with their bodies mutilated, their heads severed from their skeletons, and their arms and feet bound. Sacrificial victims were placed on top of tombs, in stairwells, in pits, on ramps, and to the right of tomb emplacements, while the sacrificed dogs were pitted to the left.xiii Other animal sacrifices were also performed on a large scale, and according to the oracle bones, as many as 1000 cattle were sacrificed for just one occasion.xiv The oracle bones also tells us that the Shang people experienced intervillage warfare, used cowrie shells (marine mollusks) as currency, and that the “king [went into battle having] set up three army units, right, center, and left.” His soldiers went to battle bearing bronze axes with iron edges, lances, spears, swords, and javelins.xv We even found out that the climate in 1200 BCE was warmer and wetter in Anyang than it is today. Oracle inscriptions describe elephant, tiger, boar, wolf, and pheasant hunts in heavily forested and marshy areas.xvi The scholar Li Hsiao-tin noted that in oracle bone inscriptions there exist 48 different characters with the mu wood or tree compound, as well as many words for small grains such as shu, millet, and ni, wild rice. The word for wheat also appears time and again, and as Li Hsiao-ting notes, while the Shang did not grow wheat, their neighbors did, and the Shang kings kept a careful eye on their neighbor’s harvests.xvii The essential features of the oracle inscriptions also suggest that the Shang was a highly sophisticated and bureaucratic culture by 1200 BCE. In order to facilitate cracks in the bones and shells, for example, Shang diviners regularized their bones and shells by 6 sanding them and carving evenly spaced grooves into them. Neolithic oracle bones had these grooves roughly scooped out, but the Shang bored and chiseled with refinement, creating one circular groove with a round bottom, intersecting another chiseled v-shaped groove. When heat was applied, usually two cracks would appear on the reverse side of the bone or shell, one vertical along the axis of the v-shaped groove, the other transverse and often perpendicular to it. What is more, several officials were necessary to divine the future. The king himself initiated all inquiries—or they were always made in the generic name of the king; then the chen jen, makes the inquiry as the king’s representative. The p’u-jen carries out the act of divination, scorching the bones and shells, the chan-jen inteprets the cracks, and the shih or archivist, transcribes the notations pertaining to the inquiry. This inquiry typically had a preface, recording the cyclical date of the question and the name of the questioner, the question put to the ancestors, and the prognostication, typically inscribed on the reverse side of the bone or shell.xviii Later, the archivist added the verification or error resulting from the act of divining.xix What seems clear from all of this sophisticated ritual involving so many bureaucratic hands is that oracle bone divination was both a religious and a political act of great power, and as such, seems to me awfully susceptible to manipulations of all sorts. As social anthropologist Levi-Strauss notes in his studies of primitive societies, the religious frame of mind, as opposed to the more antiquated magical one, believes that a power superior to humankind dominates all actions. Instead of seeking to manipulate the elements to create a hex then, the religious person seeks to gain the favor of the superior power believed to direct and control the course of nature and of human life. As 7 James Fraser notes, religious belief consists of two parts: a theoretical element and a practical one. Belief itself is theoretical, and the application of belief through prayer, sacrifice, et cetera, constitutes its practical component. As a result of undertaking such practical actions based on belief, a relationship is established between the physical world of humanity and the physically non-existent world of the superior power. Unlike in the world of magic, this religious relationship is a subordinate and intangible one, and in confirmed as a result of links created where previously, Claude Levi-Strauss notes, there were not “any sort of relation[s]” at all.xx For the Shang, the oracle bones clearly helped people make this religious link—yet what is the likelihood that those diviners and diviners involved in the linking process actually believed in it? Consider the many hands in the divination process of the Shang. Each official has a role in determining the outcome of the divination. The preparation of the bone or shell, the cutting of the grooves, the method of firing, and the act of interpretation itself all serve as potential variables in the unfolding act of faith. If the grooves were cut a certain way, wouldn’t it affect the character of the crack? Wouldn’t the method chosen for holding the bone or shell over the flame also affect it? And what does a crack say, anyway? To be sure, given the Shang propensity for human sacrifice, each of those officials who had a personal and perhaps political interest in the divine outcome of the cracked bone or shell may have felt the need to exercise some practical control over it. The later Shang emperors were known for their cruelty, for example. One invented the “grill roast punishment” whereby he roasted officials and peasants in such a way as to keep them alive for long periods of roasting. Another turned officials who displeased him into meat sauce, and burned, roasted, and chopped up people with relish and abandon.xxi 8 Thus it is not surprising that we find in the Bamboo Annals an incident wherein an oracle bone diviner hedges in his interpretation. The Emperor Kan Shin had heard that the phoenix bird was flying at the borders of his kingdom, and was very concerned. He was concerned because the lucky phoenix flies away from unruly states, and the rains kept pouring down on his land, suggesting bad luck for Kan Shin. Kan Shin ordered the diviner to consult the tortoise shell, but according to the diviner, the shell would only scorch, not crack. The diviner then suggested that Kan shin, who had just sacrificed five men to stop the rains, instead seek the counsel of his sage councillors, noting that the tortoise shell remained only scorched—not cracked-- because even the shell would not go against their sage wisdom—a seemingly convenient and perhaps shrewd political choice on the part of the diviner.xxii Likewise, the Shang dynasty ended, the The Book of Records notes, when another diviner made the shrewd political choice to escape to the lands of the rugged Chou people after the Shang emperor had cut out the heart of his superior. These were not the times, apparently, for bringing the wrong kind of news to light from the other world. Nor were diviners the only ones in need of good prognostications. Royal power also depended on them. When Shang king P’an Keng decided to move the capital across the Yellow river to Anyang, he consulted the tortoise shells and obtained the following reply: This is no place for us any longer. If we change cities, Heaven will perpetuate its decree in our favour in the new City.xxiii 9 There is, as far as we know, only the logic of faith—or political premeditation— underwriting the response of the shells and bones to P’an Keng’s inquiry, and weighing against faith is the fact that the response conveniently supported the decision the king was intent on making. Likewise, T’ang, the founder of the Shang, had another convenient experience with tortoise shells. He was contemplating the overthrow of the king who preceded him and happened to drop a gem in the water. Thereafter, a black tortoise walked by him, with red lines forming characters on its shell, telling T’ang that the ruling king was unprincipled, and that T’ang must overthrow him. In kind, when the first Chou conqueror, following the advice of the escaped Shang Junior Ritualist, went to war against the Shang, he consulted the tortoise shells and accordingly reported to his people about the consultation: The iniquity of the Shang is full. Heaven gives command To destroy it. If I do not comply with Heaven, My iniquity would be just as great.xxiv Clearly, the king’s ability to divine made him believable and thus powerful, and while history is doubtless full of kings, shamans, and officials whose divining skill never was driven by political ambition, James Frazer is one of many scholars of the ancient world who suggests that giving such matters up to actual faith was tantamount to an act of suicide. Frazer asserts in his Golden Bough that only the diviners who did not believe in their powers ultimately succeeded, because when they sacrificed victims to end the 10 rains or the droughts, or sought counsel from the oracle bones, those who did not really believe were already planning their alibis for if they did not get their intended results, wherein those who truly believed were just as shocked as the people who stoned them to death when sacrifices, prayers, and divinations of all sorts did not help the situation.xxv Thus, according to Fraser, the leadership caste of ancient tribes drew into its ranks “the ablest and most ambitious men of the tribe, those who perceive[d] how easy it is to dupe their weaker [believing] brother[s].”xxvi I will leave it up to you to consider whether the intentions of leaders are any different now than from what Fraser asserts about ancient ones, but it seems clear that if the Shang kings and official diviners wanted to create divine truth, the oracle bones and shells gave them the opportunity to suit their needs and desires. Yet even more significant perhaps than the political and religious uses of the oracle bones, and than the light they shed on Shang culture generally, concerns what they tell us about the Chinese language, for there is a link through both time and language from even before the Shang to the highly poetic character of Chinese written expression unto this day, and underwriting this link of past and present through time and language is another enduring feature of Chinese culture—a reverence for the tribe, the clan, the family. Even though the Shang had developed a fairly sophisticated set of language tools for communicating with the ghosts of ancestors, the earliest evidence of the Chinese written language is found in the ancient pottery of the Yang-shao peoples, whom we know to have flourished in Neolithic times, circa 5000 BCE.xxvii The Yang-shao were hunter gatherers, living at the far end of an ancestral lineage passing through the later 11 Shantung Lung-shan peoples (3000 BCE), probably the ancestors of the still quasi legendary Hsia Dynasty and of the historically emerging Shang.xxviii This pottery never drew much scholarly attention because a lot of it was discovered in Shensi province at another emerging Shang site at about the same time as were the exciting oracle bones in Anyang. Yet scholars now generally agree that this pottery contains some of the earliest writing ever produced by humankind.xxix Further, those early characters, according to Lo Chen-yu, Dobson, and Hurlee Creel, resemble the archaic script employed by the Shang archivists for divination.xxx Yet unlike the Shang oracle script, pottery writing—marks, really-- simply and roughly indicated the totems, emblems, and professions of members of a given clan. It was in the hands of the Shang, however, where Chinese writing took on the character traits that Chinese writing bears today. During the Shang, for example, the number of emblems and word-characters dramatically increased from a few hundred to over 4,500, of which approximately 1700 have been deciphered.xxxi Moreover, the written characters were already formed as pictographs and ideographs. That is to say, the written characters or signs resembled what they signified—pictographs-- so a tree looked like a tree, for example, a man like a man, and a sun like a sun. These character signs also were combined by the Shang to create ideas or ideographs, such as when in modern Chinese today a writer puts the pictograph for the sun halfway down the pictograph of a tree to create the idea of “east.” Moreover, borrowing occurred in Shang written expression, so that synonyms and homonyms were adopted to express different things. The character lai, for example, which served as the pictographic image of wheat, was borrowed for the homophonous 12 word meaning “to come.” The character Feng, meaning the phoenix bird, was borrowed to write the ever so loosely synonymous or metonymic word feng, meaning “wind.”xxxii These aspects of the Chinese language, born during the period of the Shang, continue to make Chinese a highly intimate and poetic language unto this day, for to the degree that the sign for a thing resembles the thing it represents, and the sonic level of linguistic expression maintains a close relationship to the pictorial one, the language retaining and employing those relationships can be said to work with an overwhelming degree of power and intimacy. Its images and its rhythms come from experiential life itself, creating through language a poetic connection between sight, sound, and sense in a way that can be said to embody language at its best.xxxiii To get a sense of the natural poetic strength of Chinese written expression, consider what connections exists in our own language between either the signs or the sounds of the words we use to describe wheat, or to describe wind, or to describe virtually anything at all. There rarely is one. Confirmed in this link of past and present through time and language is another enduring feature of Chinese culture—a reverence for the tribe, the clan, the family. It seems clear from the early pottery, for example, that when a potter or craftsman finished his work, that work would be inscribed with the emblem identifying his family clan, his familial role in that clan as father, uncle, et cetera, and as time went on, his trade or profession, or the professional use to which the pottery was to be put and the clan emblems of those who would put it to use. The potter would perhaps have traded or sold his work, but the marks he made on it suggest that any commercial transaction he entered into was secondary to his place in the clan or to the place of those who purchased and used the object he produced. So too, the Shang oracle bones rarely mention the actual 13 name of an emperor making an inquiry. Rather, those names have to be ascertained by scholars who through long study become familiar with the familial, ancestral, and clan relationships of those whose names are inscribed on the bone. In short, the invention of writing in China seems to have resulted from a societal insistence on the identification of its member’s place and station within a given clan, rather than from any specific economic need to order, label, or inventory—as has been identified as the case in the development of other language groups. This emphasis on social identification carried over into the time of the Shang, and gives us a sense of their priorities, for even as a social emphasis on economic order is in evidence in the questions posed to ancestors through the oracle bones, that emphasis was always transcribed within the network of family lineages, often for the purposes of communicating with other members of those familial networks who have passed into the religious realm of nonbeing.xxxiv The human connection mattered most in the ancient Chinese world, just as in many ways it does today, and writing from the beginning has served as one of the best means for keeping and creating those connections. And indeed, just as language possessed an astonishing ability to connect Shang family members existing on either side of the line dividing being and non-being, so too it has allowed the legendary ghosts of the Shang to begin speaking to us from the other side of the grave. Given the enduring nature of this ability, perhaps it is just a matter of time before we discover some faint voices from the grave of the still buried Hsia, voices waiting for us on inscribed bones and shells hidden in tombs, for in China especially, history and language stretch backward, even as all of humanity continues moving forward at what probably has always seemed a breath taking pace. Thank-you. 14 i John Nolde, Blossoms from the East: The China Cantos of Ezra Pound. Orono: Univ. Maine Pr. 1983. Page 435. ii Legge, Shoo King, Book of Shang, p 2. iii Benjamin Schwartz. The World of Thought in Ancient China. Cambridge: Harvard UP. 1985. Page ? iv Kwang-Chih Chang. Shang Civilization. New Haven: Yale UP. 1980. page 39. v Chang, page 45. vi Chang, page 39. vii Chang, 99. viii Chang, 90. ix Chang, 90. x Chang, 99. xi Chang, 172. xii Chang, 121. xiii Chang, 99. xiv Chang, 143. xv Shouyi, An Outline History of China. Bai Shouyi, editor. Beijing: Foreign Languages Pr. 1982. page 68. xvi Chang, 141. xvii Chang, 149. xviii Chang, 34-35. xix Chang, 35. xx Schwartz, 19-20. xxi Legge, 39. xxii Legge, 109. xxiii Chang, 11. xxiv Legge, 287. xxv Fraser, Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion. New York: Collier, 1922. Page 53. xxvi Fraser, 52-53. xxvii Chang, 337. xxviii Chang, 344. xxix Shouyi, 63 xxx Chang, 245. xxxi Shouyi, 63. xxxii Shouyi, 63. xxxiii Fenollosa, The Chinese Written Character as a Means for Poetic Expression. Ezra Pound, editor. San Francisco: City Lights Press, 1936. xxxiv Chang, 247.