Word - Special Education Policy Issues in Washington State

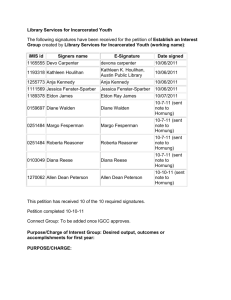

advertisement

Special Education Law Quarterly July 2006 Bulletin #9 JUVENILE JUSTICE AND SPECIAL EDUCATION STUDENTS IN WASHINGTON STATE I. INTRODUCTION Most educators have little knowledge of, or experience with, the juvenile justice system. Pre-service training focuses on curricula and teaching methodologies for use in the typical school classroom. Less attention is given to educating children who will receive their education in alternative institutional settings such as correctional facilities. And because most students in public primary and secondary schools are not in conflict with the law—either as victims or offenders—many educators will never have reason to interact with the juvenile justice system. Even school psychologists or social workers may have minimal academic or practical experience with children who are detained prior to trial or incarcerated for delinquent behavior. Unfortunately, however, it is increasingly common for educators to have some school-related involvement with the justice system. This may include instances where the police are called to the school as a result of violent behavior on the part of a student or a child returns to the classroom from detention or incarceration. The juvenile justice system operates under a different set of principles and uses a different language than the education system. Educators may be unsure of what and how the two systems can and should work together on behalf of children. And it must be acknowledged that some educators may be concerned about whether students returning to school from correctional facilities are going to be dangerous. This Special Education Law Bulletin (Bulletin) provides educators an introduction to that “other world” of juvenile justice. It provides a summary of the Washington State juvenile justice system, reviews the rights to education, including special education, for children in detention or incarceration, and offers practice suggestions for improving outcomes for students who are either at-risk for involvement with the justice system or are returning from incarceration. The focus is on the relationship between the juvenile justice system and special education in this state although information from national studies is also covered. Page 2 of 17 Special Ed Law Quarterly, Bulletin #9 II. DISABLED YOUTH IN THE AMERICAN JUSTICE SYSTEM Although there have always been school-aged children (hereafter referred to as youth) involved in the justice system—as victims or offenders—it is only recently that attention has been given to the fact that a disproportionate number of them have disabilities. There are only a few national studies that have investigated the number of disabled youth in the justice system and the statistical findings vary widely. However, there is a growing national concern about the issue and questions are being raised as how to improve interventions for at-risk children prior to any involvement with the justice system, what strategies can benefit youth while they are serving sentences, and how to minimize recidivism.1 But we are a long way from understanding any of these topics for non-disabled youth let alone disabled youth. This section of the Bulletin reviews the national research on disabled youth in the juvenile and adult justice systems. Section III focuses on disabled youth in Washington State juvenile and adult correctional facilities. A. Disabled Youth in the Juvenile Justice System Nationally, there are close to 100,000 children incarcerated in juvenile correctional residential settings on any given day.2 Extensive statistics are kept on the numbers of youth incarcerated in the United States including data on sex, race and ethnicity; however, the data does not include disability information. The latest census data is from 2003 and is broken out by sex and age in the chart below: Age on Census Date by Sex for United States, 2003 3 Age Total Sex Male Total 12 & younger 13 14 15 16 17 18 & older 96,655 1,671 4,088 9,890 18,363 24,809 23,993 13,841 82,065 1,406 3,221 7,850 14,874 20,872 21,005 12,837 Female 14,590 265 867 2,040 3,489 3,937 2,988 1,004 Due to the lack of national census data on the number of disabled youth in the justice system, we must rely on periodic national survey research. A comprehensive study done six years ago Copyright © 2006 by University of Washington. Special Ed Law Quarterly, Bulletin #9 Page 3 of 17 showed that somewhere between 45-75% of the children in the juvenile justice system have one or more disabilities.4 Part of the difficulty in getting an accurate number is, of course, related to how one defines disability. Is it only those who are found eligible for special education services—i.e., on Individualized Education Programs (IEPs)—or is it the larger number of disabled youth including those with drug and alcohol or mental health disorders that may not qualify them for special education services? If one includes the mental health disorders, at least one study indicates 90% of youth in corrections meet the diagnostic criteria.5 And it is clear that many children have dual diagnosis—i.e., drug, alcohol and/or mental health disorders and another disabling condition. The most common diagnoses among incarcerated youth in this study—other than drug or alcohol abuse—were found to be Attention Deficit Hyperactive Disorder (ADHD), Learning Disabilities (LD), Developmental Disabilities (DD), Conduct Disorder, Anxiety Disorders, and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). The study findings do not indicate whether the youth received services through special education, but we can assume that many of the youth with the diagnoses above would qualify for IEPs. This assumption is supported by a recent national survey of both adult and juvenile correctional facilities that reported approximately 33% of the juveniles have a disability that qualifies them for special education and related services under the IDEA.6 Using this conservative estimate, approximately 1/3 of incarcerated youth have a disability. This is a much higher than the estimated 10% of school age children (1/10) in the United States who are considered disabled. Why are such a disproportionate number of disabled youth incarcerated? We can posit a variety of reasons but there is insufficient research to adequately answer the question. In part it may be because schools have been legally required to refer students to juvenile justice in certain situations when previously they may not have done so; some of these will be special education students. In addition, many schools have introduced zero tolerance policies voluntarily in reaction to public concerns over violent behaviors in schools. Behavior that in the past may have been addressed within the school environment is now “criminalized” and the problem handed to the enforcement authorities. Another reason the number of disabled youth in conflict with the law may be high is that most disabled youth are living in the community—not institutional settings—and are more likely to be included in neighborhood schools where there is greater potential to be victimized and/or exhibit offensive behaviors that get them involved with the police. Although not all youth who are guilty of an offense will be incarcerated—the juvenile justice system does generally consider community based sentencing for all but the most dangerous or repeat offenders—involvement with the juvenile justice system is always a more restrictive environment regardless of the sentence. The high number may also reflect the failure of police, attorneys, judges and corrections staff to understand the characteristics related to some disabling conditions. As a result, disabled youth may be more vulnerable to involvement in the system due to poorly developed reasoning ability, inappropriate affect, and inattention to justice professionals who interpret these behaviors as signs of hostility, guilt or lack of cooperation.7 Studies investigating incarcerated youth generally—not only those identified as disabled—have reported a number of characteristics that appear to be common among all the youth. These include a below average to average IQ score, with a higher performance than verbal score, a history of school failure and limited access to mental health services and appropriate school supports, inadequate social skills, and impulsivity.8 While these characteristics are not surprising, for disabled youth it raises several tough questions. Do these common Copyright © 2006 by University of Washington. Page 4 of 17 Special Ed Law Quarterly, Bulletin #9 characteristics indicate the failure of school personnel to respond appropriately to children at risk prior to their involvement with the justice system? Specifically, did the schools properly identify children needing special education services and if so, was the individualized education program designed to address their needs adequately? B. Disabled Youth in Adult Correctional Facilities Criminal law is primarily a state government responsibility. State legislatures pass the legislation that creates both the juvenile and adult “criminal” codes. The juvenile code in most states, however, labels crimes by children as delinquent acts. As a general rule, individuals under the age of 18 who commit delinquent behavior will be adjudicated under the juvenile justice system. However, there are exceptions to this general rule and individuals under 18 years old can be transferred for adjudication in the adult criminal justice system. Transfer laws “define categories of juveniles who, because of their ages, their past records, or the seriousness of the charges against them, may—or in some cases must—be tried in courts of criminal jurisdiction.”9 Each state differs on the age at which a child can or must be transferred to the adult system; in fact, some states have no minimal age. In reaction to the increase in juvenile crime for a period of ten years beginning in the mid-1980s, many states lowered the age at which youth could be transferred for adjudication in the adult system. This resulted in an increase in the number of youth incarcerated in the adult prisons and jails around the country. The latest Department of Justice report indicates that on any given day, approximately 14,500 youth (under 18 years of age) are incarcerated in the adult system. 10 The majority of these youth are 17 and 18 years old. In Washington State, the state legislature has mandated that certain categories of offenders are excluded from the juvenile justice system and must be charged, tried and sentenced in the adult justice system. This includes offenders 16-18 years old who are charged with murder, person offenses or property offenses. Offenders younger than sixteen may be transferred to the adult system for adjudication but it is a discretionary transfer not mandatory.11 National statistics are not available on the number of disabled juveniles incarcerated in adult facilities. The recent national survey investigating the number of youth eligible for special education services under IDEA mentioned earlier included youth incarcerated in the adult system and concluded that 33% were eligible.12 Using this number, we can estimate that approximately 4,785 disabled youth eligible for special education services are serving their sentences in adult correctional facilities. The educational rights of youth incarcerated in the adult justice system—including rights to special education services—differ from youth incarcerated in the juvenile justice system. These differences will be described in Section IV following an introduction to the juvenile justice system. Copyright © 2006 by University of Washington. Special Ed Law Quarterly, Bulletin #9 Page 5 of 17 III. THE JUVENILE JUSTICE SYSTEM IN WASHINGTON STATE It has only been a little over 100 years since this country introduced a juvenile justice system. Prior to the turn of the 20th Century, children were charged, tried and sentenced under the adult criminal system. However, as society’s view of children as “miniature adults” evolved into an understanding of them as “developing human beings,” social reformers worked to change the focus of the system from punishment to rehabilitation for children. As a general principle, the juvenile justice operates under the premise that all children are less responsible for their behavior and more amenable to rehabilitation than adults. This rehabilitative model has eroded somewhat in the last ten years as states have reacted to public concern with juvenile crimes and states have passed legislation to “get tough” on young offenders. The differences between the two justice systems have not been eliminated, but there is no question that there is greater emphasis on community safety and holding youth accountable for their actions in the juvenile justice process. The increase in the number of youth transferred to the adult justice system for adjudication mentioned above is an example of this change. Although the juvenile justice system handles more than “criminal” matters—such as truancy and child neglect—this law bulletin focuses on the criminal or delinquency aspects of the system. What Happens When, During and After Arrest? When a youth is arrested, he/she is typically detained in a local detention facility pending a decision as to whether charges will be filed. There are 22 detention facilities in Washington State. If the state does file charges against a youth, he/she may be released with conditions pending trial and sentencing (disposition) or may be required to remain in detention. Youth who are indigent and charged with crimes will receive a court-appointed lawyer to defend them when the case goes to court. For the most part, youth who have committed crimes are the jurisdiction of the juvenile court. Washington has 34 juvenile courts located throughout the state. Youth who are arrested and sent to juvenile court for a trial receive most—but not all—the due process rights afforded individuals in the adult justice system.13 When youth are found guilty of an offense, judges use a set of guidelines that offer a range of sentences and conditions allowing consideration of the seriousness of the offenses committed and the history of prior offenses if any. Youth who commit a criminal felony offense are sentenced under a uniform set of guidelines that follow the Sentencing Guidelines passed by our legislature. Felony offenses are those that our state legislature has determined to be more harmful acts and a greater threat to society than other crimes. Youth who commit less serious offenses will probably receive a “local sanction.” This means that they will serve time in the local county detention facility operated by the juvenile court Copyright © 2006 by University of Washington. Page 6 of 17 Special Ed Law Quarterly, Bulletin #9 and/or to serve a period of community supervision. Youth have an assigned probation officer who enforces the court’s order for detention or community service and who works with the child on the “treatment and intervention plan” that has been developed. For all youth, this will include educational services of some kind. Our state juvenile justice system recognizes that it is in the best interest of the child in most cases to remain in his/her community rather than be sentenced to one of the state residential correctional facilities. Therefore, the state funds a variety of community-based programs or interventions as “disposition” options for some offenders including: The Special Sex Offender Disposition Alternative (SSODA) Chemical Dependency Disposition Alternative (CDDA) Mental Health Disposition Alternative Suspended Disposition Alternative Aggression Replacement Training Multi-Systemic Therapy Youth whose disposition includes community-based services will work with a probation officer who will monitor the youth’s compliance with the disposition order. This will probably include liaise with the youth’s school. Although probation officers have large caseloads, they will more likely than not be checking in with the student at school and may be well known to the student’s teachers and the building administrators B. In Custody of the Juvenile Rehabilitation Administartion (JRA) The Juvenile Rehabilitation Administration (JRA) is the state government agency under the Department of Social and Health Services (DSHS) responsible for providing services to youth who have committed serious offenses or have a history of repeated offenses and are ordered to a correctional facility or program. Youth committed (sentenced) to JRA by the juvenile courts will receive services at one of five locations in the state: Echo Glen Children’s Center, Green Hill Training School, Maple Lane School, Naselle Youth Camp, or Camp Outlook Basic Training Camp. JRA provides services to youth until age 21; most youth will either have been released prior to that age or their sentence will end on that birth date. The national census data indicates that in 2003, 1,656 youth were incarcerated in Washington State juvenile facilities; 1,443—the vast majority—were boys.14 JRA reports that incarcerated youth in this state have “both acute and complex service needs” and reports as of March 2006 that the agency tracks the following conditions: Mental Health Chemical Dependency Cognitive Impairment Sexual Offending and Misconduct Medical Fragility15 JRA use these “labels” to identify what the staff consider to be the issue that is of most concern and critical to address in developing and implementing a rehabilitation plan for the youth.16 The chart below from the JRA website indicates the percentage of youth in the correctional facilities (residential) or have been released from incarceration but still monitored by the courts (parole) who have been identified as having these “conditions.” Copyright © 2006 by University of Washington. Special Ed Law Quarterly, Bulletin #9 Page 7 of 17 What is interesting about this tracking is that is does not include disability categories as used commonly in special education—i.e., autism, deaf, etc. Nor does it tell us how many youth are on IEPs or receiving services on Section 504 plans. There is no statewide tracking of disabled students in correctional facilities in Washington. As is discussed further below, educational services are provided by the school district in which the facility is located and the record keeping is at the local district level. The youth in Washington State correctional facilities more likely than not have 2 or more cooccurring conditions as indicated on the chart below: Both charts are located at http://www1.dshs.wa.gov/jra/ServiceNeeds.shtml Professionals from a variety of disciplines acknowledge the importance of addressing the specific needs of all youth in conflict with the law—whether incarcerated or not—to help them minimize the behaviors and/or resolve the problems that have led to involvement with the justice system. It would seem obvious that youth would receive intensive educational services addressing their specific needs while in the custody of the state to maximize their Copyright © 2006 by University of Washington. Page 8 of 17 Special Ed Law Quarterly, Bulletin #9 chances of avoiding involvement with the law in the future. However, the educational rights of incarcerated youth have not always been recognized. IV. EDUCATIONAL RIGHTS OF YOUTH OFFENDERS In 1967, the United States Supreme Court ruled in In re Gault17 that youth arrested and sentenced in the juvenile justice system must have their Constitutional rights to due process recognized by state justice systems. Washington State passed the Juvenile Justice Act (JJA) in 1977 in part to ensure that those rights were protected in the juvenile system. The legislature addressed the importance of education to youth offenders in the JJA; however, subsequent case law has clarified that the rights of incarcerated youth are not identical to rights of other youth. This section of the Bulletin summarizes those cases and the state law that is relevant. A. General Education Rights The Washington State Constitution states that it is the “paramount duty” of the State to provide all children with “ample access” to an education and requires the state to provide this education through “a general and uniform system of public school.”18 The State Legislature passed the Basic Education Act to ensure that the state “provide students with the opportunity to become responsible citizens, to contribute to their own economic well-being and to that of their families and communities, and to enjoy productive and satisfying lives.”19 Our state commits that a public school education will be available to all children ages 5-21. The state Special Education Law requires that all disabled students ages 3-21 have an appropriate educational program available.20 Neither of these laws specifically addresses the rights of youth who are detained in county detention facilities or incarcerated in youth facilities under the control of JRA. It has long been clear that incarcerated youth, including disabled youth, have a right to education services while under the control of the state. However, the issue of educational rights while in detention has been a matter of debate as described below. The legal question raised in Tommy P. v. Board of Cty. Comm’rs21 was whether Washington State had a duty to provide education to youth who were detained in juvenile detention facilities—which is typically a short stay although can be months in some cases. Tommy P was a class action, meaning that the plaintiffs represented “all juveniles of compulsory school age” who were held in the Spokane County Juvenile Detention facility. The position of the County was that is did not have to provide educational services to youth in the pre-trial, preadjudication phase of the process. The judge disagreed and found that the time in detention facilities could be lengthy depending on the case and the educational needs of this population “often extensive.” Therefore, the court held that the purposes of the JJA and the compulsory education laws in the state required that detention facilities provide education to those youth who had been detained. As a result of this decision, the state legislature passed a law that requires the Department of Social and Health Services (DSHS) and the school districts where the detention facilities are located to provide a program of education to all “common school age juveniles in detention Copyright © 2006 by University of Washington. Special Ed Law Quarterly, Bulletin #9 Page 9 of 17 facilities.”22 Common school age juveniles are those between the ages of 8-21 years under state law. So regardless of how long or short the stay in detention, all youth have a right to receive educational services while there. And that education—including special education— will be provided by the local school district in which the detention facility is physically located. B. Special Education Services in Juvenile Correctional Facilities As the national studies show, disabled youth—many who are eligible for special education services—are incarcerated in both juvenile and adult correctional facilities. And many have shown to have few of the skills necessary to be successful in the community as illustrated in the following statement: About one third of prisoners are unable to perform such simple job-related tasks as locating an intersection on a street map, or identifying and entering basic information on an application. Another one-third are unable to perform slightly more difficult tasks such as writing an explanation of a billing error or entering information on an automobile maintenance form. Only about one in twenty can do things such as use a schedule to determine which bus to take. Young prisoners with disabilities are among the least likely to have the skills they need to hold a job. For them, education is probably the only opportunity they have to become productive members of society.23 Institutional education has been shown to have a “clear, positive effect in reducing recidivism and increasing post-release success in employment and other life endeavors.”24 Thus the importance of education for incarcerated youth cannot be underestimated and is as critical— if not more so—for students who are eligible for special education services. Disabled youth have rights under several federal laws including Title II of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 (Section 504) as well as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act (hereafter IDEA) 2004 and in our state the Washington State Law Against Discrimination (RCW 49.60). However, this Bulletin focuses on the rights of youth and the duty of the state under IDEA. Specifically, what does the federal special education law—IDEA—require of schools when disabled students enter the justice system? In answering the question, it helps to start with the language of the statute and the recently released federal regulations.25 This Bulletin is not intended to cover all aspects of the IDEA, but instead focuses on aspects of the IDEA that have particular importance to youth who are involved with or are at risk for involvement with the justice system. First, a comment concerning the application of IDEA to incarcerated youth. All children in this country between the ages of 3-21 who meet the eligibility criteria under IDEA are entitled to a free appropriate public education (FAPE). It is important to remember that all the IDEA rights apply to eligible incarcerated youth with the exception of youth ages 18-21 who, in his or her last educational placement prior to incarceration in an adult criminal corrections facility, was not actually identified as a child with a disability and did not have an IEP under part B.26 However, the specific application of those rights may differ because of the fact that a youth is under a court order disposition to remain institutionalized while under the jurisdiction (control) of the state. Copyright © 2006 by University of Washington. Page 10 of 17 Special Ed Law Quarterly, Bulletin #9 Identification and Evaluation of Eligible Students The duty of the state to provide special education services to eligible students who are incarcerated is generally the same as the duty outside a correctional facility. The child-find obligation is a good example. States are obligated to implement child-find activities throughout the state to locate children who may require special education and related services in order to benefit from public instruction. The duty extends to all locations where children may be including hospitals, institutions, private schools etc. Therefore, states must “find” eligible children even in detention or correctional facilities and if appropriate, assess and develop appropriate IEPs. This could occur at many different steps in the juvenile justice system but certain should occur at the latest when a child enters detention or is incarcerated. Routine screening at intake points should include questions related to school experiences that will provide clues as to whether the youth has been in special education, received special classes or has a spotty educational history that raises questions of eligibility. Having access to prior school records is obviously important and the IDEA requires local educational agencies (LEAs) to forward special education and disciplinary records to the justice authorities when they report that a child has committed a crime.27 Evaluation of youth suspected of having special education needs must occur even if the youth will not be in the facility long enough to complete the process. If that occurs, facilities should send the information they do have on to the next educational placement—whether that is a community school or another institutional setting. Interim Services and Implementation of IEPs If a youth with an IEP arrives in detention or is incarcerated, the school must implement the existing IEP or hold an IEP meeting as required by law. If the institutional special education staff proposes to modify the existing IEP, they still must provide comparable services until the new one is developed. And IDEA requires that the IEP be implemented as soon as possible after meetings are held. It is very common for a youth to arrive in the system without a current IEP or having been out of school for a substantial period. If this is the case, the best practice is to recognize the fact that a history of previous special education eligibility strongly suggests the youth needs to be evaluated for services. The range of options available to the districts responsible for institutionalized education to ensure that the IEP is implemented in the least restrictive environment (LRE) will be less than would be available on the “outside.” Nonetheless, there must be a continuum of placements available even within the limitations of the justice system. For example, institutions may not provide one generic special education program and implement all IEPs in that placement. An incarcerated youth has the right to receive his/her services in the LRE available within the correctional system and to be served with nondisabled youth to the maximum extent appropriate. Related to this is the issue of discrimination disincentives. Institutions may not offer special education services that will compete with more “desirable” options available to nondisabled youth such as vocational classes or extracurricular activities such as sports.28 Even in lock-down situations—where youths’ mobility is restricted to an even greater degree— special education services as described on the IEP must be provided. IDEA does mention Copyright © 2006 by University of Washington. Special Ed Law Quarterly, Bulletin #9 Page 11 of 17 modification of IEPs for youth incarcerated in adult criminal corrections facilities if there is a “bona fide security or compelling penological interest,” no such authorization exists for juvenile incarceration.29 Therefore, the “normal” rules would seem to apply in a lockdown situation and if the behavior that caused the transfer is school related, it triggers all the due process protections that result from a “change of placement” including a review of behavioral intervention plans (BIPs), functional behavioral assessments, manifestation determinations, and time limits on exclusion.30 It goes without saying that BIPs for incarcerated youth should include close communication between JRA staff and educational professionals as the focus on addressing inappropriate behavior is of concern to both state agencies. Due Process Protections All the due process protections in IDEA are available to incarcerated youth—and they are of particular importance to this population of vulnerable youth. All youth (and their parents, guardians or surrogates) should receive information on their special education rights. Parents—unless a court has limited their rights—should continue to be apart of the IEP team. These due process rights are in addition to any juvenile justice institutional grievance procedure. The right to challenge the failure to provide FAPE through administrative channels, individual lawsuits, or class-action litigation is also available to youth who are incarcerated. And dozen of decisions have been issued—both administratively and judicially— on a wide range of issues including identification, access to educational records, IEP development, service delivery, staff qualifications, as well as compensatory education for failure to provide special education services.31 C. Washington Youth Incarcerated in Adult Correctional Facilities Youth who are sentenced to adult correctional facilities do not have the same rights to education in our state—regular or special education—as do those in juvenile correctional facilities. The Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction (OSPI) had no duty to provide education to any youth incarcerated in adult facilities (Washington Department of Corrections) until 1998. That year the legislature passed RCW 28A.193 which required OSPI to “solicit proposals from educational entities to provide education to inmates under the age of 18 in Washington State prisons.” That seems straightforward but it was unclear as to whether inmates between the ages of 18-21 had rights to education because the Basic Education Act and the Special Education Act both provided educational rights up to age 21 and possibly age 22 in the case of special education. These existing statutes appeared to clash with the new RCW 28A.193 and the confusion resulted in a court case. Tunstall v. Bergeston32 was brought by “all individuals who are now, or who will in the future be, committed to the custody of the Washington Department of Corrections (DCO), who are allegedly denied access to basic or special education during that custody and who are, during that custody, under the age of 21, or disabled and under the age of 22.” The Washington court did not agree with the plaintiff class and ruled that the state had a duty only to provide education, including special education, to inmates until their 18th birthday. This differs from the federal IDEA that allows special education services, if not contrary to state law, to be provided to youth in adult facilities. Therefore, if a youth with an IEP is adjudicated and Copyright © 2006 by University of Washington. Page 12 of 17 Special Ed Law Quarterly, Bulletin #9 sentenced in the adult system, he/she will receive special education services only until his/her 18th birthday. V. YOUTH OFFENDERS AND SPECIAL EDUCATION In the best of all worlds, youth in need of special education services would be identified early, have IEPs that include services designed to address any problem behaviors that interfere with education, and would not participate in delinquent or criminal behavior that leads to involvement with the justice system. Unfortunately, given the disproportionate number of disabled youth incarcerated, we are clearly not living in that world. However, educators are increasingly working with the juvenile justice system to improve the outcomes for youth who are at risk for involvement with the criminal system and/or returning from incarceration. This section of the Bulletin offers food for thought for educators including information on state resources. A. Practice Consideration Research has shown that criminal behavior is “strongly linked to a number of factors including dropping out of school, substance abuse, a weak family structure, poverty, and learning and behavioral disabilities, among others.” 33 Research has also shown that outcomes for youth in conflict with the law are better when “interventions are provided through community-based, family-focused, and prevention-oriented collaboration” rather than the more punitive, segregated approach offered through incarceration.34 The educational system cannot be responsible for “correcting” all the underlying factors that contribute to criminal behavior among youth. But what practically can special educators do to help improve the outcomes for disabled youth who are at-risk for involvement with the juvenile justice system? Early Identification and Intervention Educators can help support at risk children through early identification of youth with behavioral concerns and providing appropriate interventions for those eligible for special education services. Before problem behaviors result in disciplinary action, educators can advocate for students who are clearly at risk by ensuring that IEP development includes consideration of behavioral intervention strategies to minimize problematic behaviors. Mental Health Resources Secondly, special educators can become familiar with community-based resources for students—those with IEPs or Section 504 plans—who have mental health concerns. Ensuring that at-risk children are referred for services as soon as the need is recognized could be a powerful strategy in redirecting a student from involvement with the justice system. Increasingly, schools in Washington are linking with community based mental health services to ensure that students dealing with depression or other mental health disorders have access to the resources they need. A previous Bulletin addressed this issue and is available at http://wea.uwctds.washington.edu/HTML%20Bulletins/Bulletin7.html and more information is available on the OSPI website. Discipline Issues Copyright © 2006 by University of Washington. Special Ed Law Quarterly, Bulletin #9 Page 13 of 17 The discipline of special education students has been a focus of litigation for many years as schools balance their responsibilities to maintain safe learning environments for all children and staff at the same time providing education to all disabled students in the least restrictive environment (LRE). Previous Bulletins available at http://wea.uwctds.washington.edu/HTML%20Bulletins/Bulletin4.html and http://wea.uwctds.washington.edu/HTML%20Bulletins/Bulletin3.html addressed the discipline of special education students and educators’ rights and responsibilities when working with violent students. Although there have been changes in the most recent 2004 amendments to the IDEA, those changes are discussed in a recent Bulletin at http://wea.uwctds.washington.edu/HTML%20Bulletins/Bulletin8.html. The reader is referred to those Bulletins for the details of the disciplinary requirements under IDEA. A couple of issues should be highlighted, however, when discussing the connections between special education and the juvenile justice system. First, the IDEA does allow schools to remove disabled students whose behavior involves weapons, illegal drugs or serious bodily harm to an Interim Alternative Educational Setting (IAES) for not more than 45 school days.35 However, except in these circumstances, the 2004 amendments continue to stress the duty of schools to provide services in the “regular” school environment by ensuring appropriate interventions are provided. Second, the IDEA gives schools the right to report a crime committed by a disabled child to the appropriate authorities as they would a nondisabled student.36 The language of the statute is: (A) Nothing in this part shall be construed to prohibit an agency from reporting a crime committed by a child with a disability to appropriate authorities or to prevent State law enforcement and judicial authorities from exercising their responsibilities with regard to the application of Federal and State law to crimes committed by a child with a disability.37 It is important to note that this authorization is to report “crimes” allegedly committed by a child. As stated earlier in this Bulletin, crimes are typically those offenses that are referred not to juvenile justice but to the adult justice system. Problem behaviors—referred to as delinquent behavior—and within the jurisdiction of the juvenile justice system are not apparently included in the IDEA statute. However, the IDEA also requires that consideration be given to the relationship between the behavior and the disabling condition. If the behavior was caused by the disability or even “related” to it, the disciplinary responses of the school might be different than if there was no nexus. Schools must be safe environments for all—students and staff—and special education students who are causing harm to others or to themselves may well need to be removed from the school environment. And some special education students will commit offenses that require referral to the “appropriate authorities.” But as one commentary stated, “zealous reporting of ‘crimes’ by special education students, particularly if such conduct is related to their disability, may be an inappropriate and costly remedy for a school district which has failed to ensure that the child otherwise receives the protections of the IDEA.”38 If students are reported to the justice system, schools must follow the state law requiring that a student’s educational records be available to the justice system.39 If the child has a Copyright © 2006 by University of Washington. Page 14 of 17 Special Ed Law Quarterly, Bulletin #9 previous conviction, the prosecutor can request those records on arrest; if no previous conviction, the records can only be released when the juvenile is convicted. Schools must have a subpoena or court order prior to releasing records requested under this law.40 B. Juvenile Offenders Returning to the Schools When youth offenders return from incarceration or detention, schools are notified. Under state law, the juvenile court must notify school principals of a youth’s conviction, adjudication or diversion agreement pertaining to a specific set of crimes including violent offenses and sexual offenses. However, the law also recognizes the importance of privacy.41 Therefore, the principal then must only provide this information to the teachers and “any other personnel who…supervises the student or for security purposes should be aware of the student’s record.”42 But the statute clearly states that this information is confidential and must not be shared outside of the legal parameters—i.e., only to those with a need to know the information in their professional capacity. Transition Services Transition plans for special education students are typically thought of as the IDEA defines them—i.e., a coordinated set of activities that “is focused on improving the academic and functional achievement of the child with a disability to facilitate the child’s movement from school to post-school activities.”43 However, for youth involved with the justice system, a transition plan also refers to the passage of a student from community settings—i.e., schools— to correctional settings and back to school again. Once a student is incarcerated, JRA reports that more than 60% are receiving mental health services while institutionalized. Eight-five percent of those youth have other disorders including chemical dependency, cognitive impairment, sexual misconduct and/or medical fragility. There are extensive services available to youth while incarcerated including Mental Health Treatment Coordinators who assist youth transitioning back to the community. For students returning to school, including these coordinators in the planning for reentry into school would help educators design appropriate interventions and support services.44 Although not all returning offenders will be special education students of course, many will have IEPs while incarcerated. Hopefully, there has been good transition planning for these students so that when they do enroll again in a community school, the receiving school has a current IEP and has received the necessary reports from the district providing services in the institution. If a returning student does not have institutional records that indicate services were provided as part of special education, but the student is suspected of having a disability, the “usual” process for referral and evaluation should be implemented. One way to address the complex needs of many at-risk children or returning offenders is to develop wrap-around services. Wrap-around services have been defined as “long-term, collaborative partnerships among schools and community service agencies.” Schools are familiar with this type of collaboration for youth with mental health/drug and alcohol concerns and with community agencies during transition planning for special education students. Particularly for youth transitioning back to the school setting from incarceration Copyright © 2006 by University of Washington. Special Ed Law Quarterly, Bulletin #9 Page 15 of 17 and/or exiting the school system from incarceration, helping develop a “safety network” of community services for that student can mean the difference between success and failure. The Washington State Reentry Project (Reentry) is funded by OSPI. It is a resource available to young offenders returning to the community. Education Advocates are available to provide “returning offenders with the help they need in order to attain their academic goals.” As part of this, videoconferencing is available to connect communities with youth offenders prior to their release. The intent is to assist the youth prepare to reenter the community by connecting with family members, neighbors, clergy, mentors, educators and potential employers. Reentry calls these community members the “Readiness Team” and is piloting the videoconferencing activity in several counties. More information is available at http://www.goinghomewashington.net/pages/main.html. Sex Offenders Included in the group of returning juvenile offenders may be sex offenders; some of whom will be special education students. There are approximately 170 juvenile sex offenders incarcerated in Washington and about 320 are under parole supervision.45 Juvenile sex offenders are obligated to follow the state sex offender laws. This means that they are required to register with law enforcement when released to the community, are prohibited from enrolling in the same school as their victim or victim’s siblings and are assigned a risk level classification for purposes of community notification by law enforcement. The risk level classification ranges from Risk Level 1 (lowest risk for reoffense) to Risk Level III (highest risk for reoffense). An interagency committee determines the risk level for each offender. The risk level designation is primarily for law enforcement and is related to what information can be released to the community. Schools are understandably concerned when students reenter the public school system following treatment for a sexual offense. However, these students have rights to public education services and they cannot be prevented from enrolling in school although as noted above—not in the school that their victim or victim’s siblings attend. All returning sex offenders will have close supervision by the courts and probation officers working with them. TeamChild is a good resource for students and educators. It is a children’s advocacy project with offices around the state. Attorneys with the organization work “with schools, social workers, probation officers, juvenile court judges among others to help youth get the support they need to succeed.”46 Their experience includes working with children involved with the justice system, returning to schools from incarceration, or facing suspension or expulsion. Although it is understandable that schools might be nervous when juvenile offenders return to the community based school setting, they have a right to an education like all children in this state. And the research indicates that being in school—and hopefully succeeding in the environment—is important in developing the skills youth need to be productive citizens. Although many of these youth have complex needs and may be very difficult students, there are community resources available that will collaborate with educators to ensure that youth in conflict with the law receive the services they need to succeed. Copyright © 2006 by University of Washington. Page 16 of 17 Special Ed Law Quarterly, Bulletin #9 VI. ADDITIONAL WEB-BASED RESOURCES For readers who are interested in additional information on juvenile justice and disabled students, or special education services generally, the following are excellent web-based sites. National Center on Education, Disability, and Juvenile Justice (EDJJ) publishes EDJJ Notes on line at www.edjj.org United States Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. On line at www.ojp.usdoj.gov/ojjdp Wrightslaw www.wrightslaw.com/info/jj.index.htm U. S. Department of Education http://www.ed.gov/policy/speced/guid/idea/idea2004.html. Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction (OSPI) http://www.k12.wa.us/ Washington State Institute for Public Policy http://www.wsipp.wa.gov/intro.asp Going Home Project: Reentry http://www.goinghomewashington.net/pages/main.html Educational Institution contacts in the state available at http://www.k12.wa.us/InstitutionalEd/pubdocs/contacts.doc Transition back to community planning http://www.edjj.org/focus/TransitionAfterCare/index.html National Council on Disability (2003, May). Addressing the needs of youth with disabilities in the juvenile justice system: The current status of evidence-based research. Washington, D.C. http://www.ncd.gov/newsroom/publications/2003/juvenile.htm The number of incarcerated youth in this country continues to drop as does the rate of violent crime among youth The societal perception that youth are getting “more violent” is not supported by the statistical data that show just the opposite. Nonetheless, approximately ¼ of the incarcerated youth nationally are serving sentences for violent offenses. 1 Sickmund, M., Sladky, T.J., Kang, Wei. (2004). Census of Juveniles in Residential Placement Databoook” online http://www.ojjdp.ncjrs.org/ojstatbb/cjrp/asp/Age_Sex.asp 2 Id. http://ericec.org/digests/e621.html 5 Otto (1995) as cited in Stenhjem, P. Youth with disabilities in the juvenile justice system: Prevention and intervention strategies. Vol. 4, Issue 1 National Center on Secondary Education and Transition (February 2005) available at http://www.ncset.org/publications/viewdesc.asp?id=1929 6 Quinn, M.M., Rutherford, R.B., Leone, P.E., Osher, D.M., Poirer, J.M. (in press). Youth with disabilities in juvenile corrections: A national survey. Exceptional Children. 7 Id. 3 4 Copyright © 2006 by University of Washington. Special Ed Law Quarterly, Bulletin #9 Page 17 of 17 Foley, R.M. (2001) Academic characteristics of incarcerated youth and correctional educational programs. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 9, 248-259. 9 Griffin, P. (October 2003). “Trying and sentencing juveniles as adults: an analysis of state transfer and blended sentencing laws.” Technical Assistance to the Juvenile Court. Special Project Bulletin. 10 http://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/bja/182503.pdf Statistics are only available nationally from 1998 study. 11 Griffin, P. (October 2003) Trying and sentencing juveniles as adults: an analysis of state transfer and blended sentencing laws. Technical Assistance to the Juvenile Court. Special Project Bulletin. 12 The Federal Department of Justice reports that approximately 12% of these are under the age of sixteen. 13 In re Gault, 387 U.S. 1 (1967). 14 Sickmund, et al. 15 http://www1.dshs.wa.gov/jra/ServiceNeeds.shtml 16 personal phone call with Rebecca Kelly, JRA 17 387 U.S. 1 (1967). 18 Washington State Constitution Art. IX §1 19 RCW 28A.150.200 20 RCW 28A,155 21 97 Wash.2d 385, 395, 645 P.2d 697 (1982). 22 RCW 28A.190.010 23 http://www.ncjrs.gov/html/ojjdp/2000_6_5/page3.html Juvenile Justice Bulletin (July 2000). “Youth with Disabilities in Institutional Settings.” 24 Id. 25 Final regulations are available at http://www.ed.gov/policy/speced/guid/idea/idea2004.html 26 34 C.F.R. 300.102(a)(2)(i) 27 34 C.F.R. 300.535(b)(1)(2). 28 Lee, A and Pattison, B. (July-August 2005) Meeting the civil legal needs of youth involved in the juvenile justice system. Clearinghouse Review Journal of Poverty Law and Policy 195. 29 Id. 30 Id. 31 Youth Law Center (1999) as quoted in http://www.ncjrs.gov/html/ojjdp/2000_6_5/page3.html. 32 141 Wash.2d 201 (2000). 33 Stenhjem, P. (February 2005). Youth with disabilities in the juvenile justice system: Prevention and intervention strategies. Vol. 4, Issue 1 National Center on Secondary Education and Transition available at http://www.ncset.org/publications/viewdesc.asp?id=1929 34 Id. 35 20 U.S.C. 1415(k)(1)(7); 34 C.F.R. 300.530(g). 36 20 U.S.C. 1415(k)(6); 34 C.F.R. 300.535. 37 20 U.S.C. 1415(k)(6) 38 Brooks, K; Schiraldi, V. Ziedenberg, J. (June 2000). “School house hype: Two years later.” Kentucky Children’s Rights Journal, Vol.VIII, No. 1 at 497. 39 RCW 13.40.480 40 RCW 28A.600.475 41 RCW 13.04.155 42 RCW 13.04.155(2). 43 34 C.F.R. 300.43(a). 44 http://www1.dshs.wa.gov/jra 45 Id. 46 http://www.teamchild.org/resources.html 8 Copyright © 2006 by University of Washington.