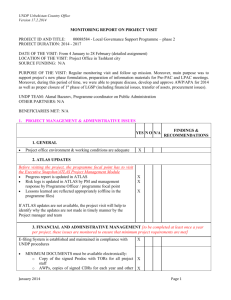

District Specific Evaluation Reports

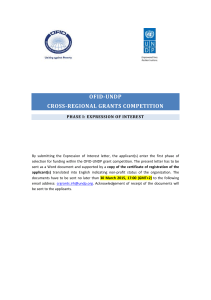

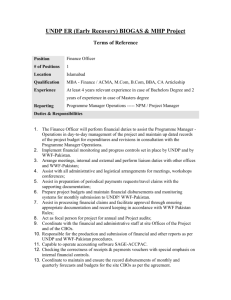

advertisement