Supplemental Data

advertisement

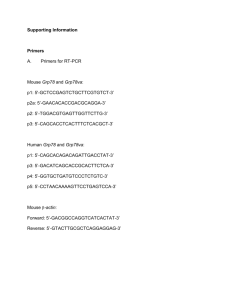

Supporting Information Materials and Methods Western blotting Embryonic stem cells (ESCs) derived from E3.5 Grp94+/+ and -/mouse embryos were maintained on feeders in ESC specific media with leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) added. Western blots were performed as previously described.1 In brief, lysates from the untreated or 6 h 300nM ER stress inducer thapsigargin (Tg) treated cells were extracted in ice-cold RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS) containing cocktails of proteinase inhibitors and phosphatase inhibitors (Roche), by centrifugation (13000g, 15 min) following 3 freeze-thaw cycles. Proteins were separated by 6%, 8% or 10% SDS-PAGE, and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (Pall). The primary antibodies used include the following: rat anti-GRP94 (1:5000) from Stressgen; rabbit anti-PERK (H-300) (1:500), rabbit anti-GADD34 (1:1,000) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology; rabbit antiphosphorylated PERK (Thr980) (1:500), rabbit anti-phosphorylated eIF2 (1:1000) and rabbit anti-eIF2 (1:1,000) from Cell Signaling; mouse anti- -actin (1:5000) from SigmaAldrich. The experiments were repeated two to three times. RT-PCR analysis of Xbp-1 mRNA splicing The cells were either untreated or treated with 300 nM ER stress inducer thapsigargin (Tg) for 6 h. After that, total RNA was extracted using TRI reagent (Sigma-Aldrich) following the manufacturer’s instructions. First-strand cDNA was synthesized with SuperScript II (Invitrogen). To detect both unspliced and spliced Xbp-1 mRNA, PCR was performed as described,2 using primers 5’-GAACCAGGAGTTAAGAACACG-3’ and 5’- AGGCAACAGTGTCAGAGTCC-3’. RT- PCR of -actin was performed as control at the same condition using primers 5’GACGGCCAGGTCATCACTAT-3’ and 5’-GTACTTGCGCTCAGGAGGAG-3’. These experiments were repeated three times. Supporting Information References 1. Li J, Ni M, Lee B, Barron E, Hinton DR, Lee AS. The unfolded protein response regulator GRP78/BiP is required for endoplasmic reticulum integrity and stressinduced autophagy in mammalian cells. Cell Death Differ 2008; 15: 1460-1471. 2. Mao C, Dong D, Little E, Luo S, Lee AS. Transgenic mouse models for monitoring endoplasmic reticulum stress in vivo. Nat Med 2004; 10: 1013-1014. Supporting Information Figure Legends Figure S1 Mice with Grp78 conditional knockout in the Purkinje cells developed postnatal growth retardation. (a-b) Fasting body weight of Grp78 F/- mice and their Grp78 F/-; pc-Cre littermates was measured weekly from 3 to 10 wk old. Both male (a) and female (b) Grp78 F/-; pc-Cre mice exhibited significantly lower body weights than the sex- and age-matched Grp78 F/- mice. Data are presented as mean±s.e.m. n=10 for each group. *p≤0.05, **p≤0.01, ***p≤0.001 (Student’s t-test). Figure S2 Purkinje cell-specific knockout of GRP94 caused no morphological or behavioral defect. (a) Representative immunohistochemical (IHC) staining for GRP94 on the sagittal sections of Grp94 F/F mice and their Grp94 F/-; pc-Cre littermates cerebella at 5 month of age. (b) Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining on the cerebellum sections of Grp94 F/F mice and their Grp94 F/-; pc-Cre littermates at 5 month old, demonstrating the Purkinje cell morphology. (c) Graphical representation of results of rotor rod test (rotating at 30 rpm) given to the Grp94 F/F male mice and their Grp94 F/-; pc-Cre male littermates for 5 trials at 5 month old, n=5 for each group. The time of 120 sec denotes that the mice stayed on the rod for the duration of the test and none fell off the rod. Scale bars represent 50 m (a) and 100 m (b). Fig S3 Knockout of Grp94 has no effect on UPR signaling pathways. (a) Grp94+/+ and -/- mouse embryonic stem cells (ESCs) were either untreated or treated with 300 nM ER stress inducer thapsigargin (Tg) for 6 h. The cell lysates were subjected to Western blotting. Lanes that were run on the same gel but noncontiguous are divided by lines. The size of the proteins (in kDa) is indicated on the left. (b) XBP-1 splicing is not affected by Grp94 knockout. Grp94+/+ and -/- ESCs were treated the same as in panel (a). Total RNA was subjected to RT-PCR for detection of the unspliced (u) or spliced (s) form of XBP-1. The size of the PCR products (in bp) is indicated on the left. For all panels, the experiments were repeated two to three times. Figure S4 Reduction of protein ubiquitination status in the prostate epithelial cells of the Grp78 prostate conditional knockout mice. (a) Representative immunohistochemical (IHC) (upper panel) and immunofluorescence (IF) (lower panel) staining for GRP78 on the ventral prostate of the Grp78 F/F mice (control mice) and their Grp78 F/F; PB-Cre littermates (the prostate epithelial cell-specific knockout mice) at 5 month old. PB-Cre refers to cre-recombinase driven by the probasin promoter. (b) IF staining for GRP78 (Red) and ubiquitin (Green) on the ventral prostate of Grp78 F/F mice and their Grp78 F/F; PB-Cre littermates at 5 month old. Blue: DAPI. Scale bars represent 200 m (a) and 50 m (b). Figure S5 ER expansion and protein aggregation inside the ER of GRP78 null PCs. (a) Representative Purkinje cell electron micrograph of a 3.5 wk old F/- mouse cerebellum shows normal Purkinje cell ultrastructural morphology. The white arrowheads indicate normal ER structure. (b) Electron micrograph of a 3.5 wk old F/-; pc-Cre mouse cerebellum shows prominent expansion of the ER in the perikaryon and proximal apical dendrite. (c) Higher magnification of the proximal dendrite area shown in panel B. Electron-dense aggregates inside the ER are indicated by the yellow arrowheads. (d) Varying degrees of electron-dense aggregates inside the expanded ER of the GRP78 null PCs as indicated by yellow arrowheads. I to III indicate increasing amount of electron-dense materials inside the expanded ER. Scale bars represent 5 m (a-b), 3 m (c) and 0.5 m (d). Supporting Information Video Legend Representative movement of Grp78 F/- mice (agouti, male) and its F/-; pc-Cre littermate (black, male) at 5.5 wk old.