independence

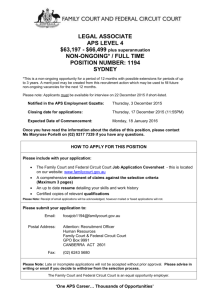

advertisement