Church of St Materiana, Tintagel Introduction St Materiana is the

advertisement

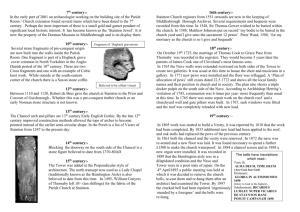

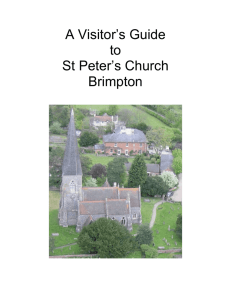

Church of St Materiana, Tintagel Introduction St Materiana is the best example of a small Norman parish church in Cornwall but its interpretation as previously established has been flawed in some respects. A few years ago after the internal walls had been stripped of their plaster prior to repairs the opportunity to examine the building fabric was invaluable, and, since repair much of this evidence shows through the lime wash that now replaces the former plaster. Some features had been interpreted as evidence for a former crossing tower to a Norman cruciform church. This interpretation is now challenged by the recent discoveries. The building is now seen as having a Norman nave and chancel plus a slightly later Norman north chapel. The transepts seem to have been planned in the late 12th century but were not constructed until the 13th century, firstly the north transept, then the longer north transept by about 1300. The tower is 15th century, having original Perpendicular features (panelled tracery) so not 14th century as had previously been claimed. The church is built near the site of an earlier oratory, the site of which, just north of the present church, was excavated a few years ago by Professor Charles Thomas and Jacky Nowakowski. Building Description Date The nave and chancel of the present church is Norman. Later in the 12th century a chapel was built north of the chancel. The porch is much repaired but appears to belong to the Norman church. The way the coursing of the walling ramps up relating to the porch and over the south doorway looks intentionally designed for a porch to be attached. Also there is little erosion to the Norman doorway in the south wall of the nave, within the porch. A Norman impost stone in the south-west corner of the crossing suggests that the transepts were planned in the 12th century. However, the north transept was built first in the 13th century, its east 3-light east window original to the structure. Similarly, in the south transept the surviving c1300 east windows with trefoil heads show no sign of disturbance and are original to the transept. Neither does the south transept show any evidence of lengthening as has been suggested. The west tower is clearly 15th century in date according to original Perpendicular windows that it contains. A small ‘aisle’ to the north of the choir was widened in the late 19th century and the arch leading to it is also 19th century so the date of the earlier structure is now difficult to establish. In 1852 Norman wall paintings with Romanesque arches and zig-zag ornament were discovered but subsequently destroyed. Despite the muddled layering of this painted scheme it would not present insurmountable difficulty to expert restoration methods of today. The loss of such an important scheme is now deeply regrettable. The upper part of the rood screen was reinstated at this time, a much more successful enterprise.. There was a restoration of 1868-1870 by Piers St Aubyn with the Rector, Mr Price of Torrington. This work included the replacement of the roof In 1872 Sedding observed pointed arches to the transepts. These were subsequently removed. The building was restored by Sedding in 1881. Materials The church is built from shallow quarried local slate-stone, the stones of generally small size and tightly fitted together as is typical of early masonry. The tower is built from larger pieces of slate-stone that are as much as possible laid to continuous courses. Dressings are cut from local green elvan (volcanic aglomorate), from nearby cliff quarries, except for replaced features that have been carried out in Polyphant stone from a quarry near Launceston. The roof coverings have been replaced but in local slate laid to random widths and diminishing courses Plan development The original 12th century church was a simple nave and chancel plan. This was extended later in the 12th century with a small chapel in the form of a transept at the north side of the chancel. A communicating doorway was cut through and the north window at the east end of the chancel was made redundant. The porch is possibly original to the building and has C12 imposts to its doorway, the arch reconfigured at some time to give a slightly pointed head (see also Date). The north transept was added probably in the mid 13th century, the longer south transept added probably about 1300. Angled masonry on the corner between the south transept and the chancel belongs to a former squint (hagioscope), its opening just visible in the north-east corner of the south transept and as jamb masonry in the south-west corner of the chancel. In the angle between the nave and the north transept is similar angled masonry. This also must have belonged to a squint, in this case presumably to gain visual access to communion in front of the east altar of the transept. Internally, there is an angled joint in the wall low down below an inserted window opening, its insertion causing the corner walling to be rebuilt removing further evidence of this feature. The angled masonry relating to the transepts has previously been interpreted as evidence for a former crossing tower. A west tower is the final medieval addition, possibly early-mid 15th century but the square hoodmoulds of the windows of the upper stage suggest a later 15th century date. A lean-to vestry between the north transept and the chapel was rebuilt to a slightly deeper plan than an older lean-to. Exterior The south wall of the nave has an original Norman window left of the porch and a wide 3light early Gothic style window at far right that was inserted in the late 19th century. The west jamb of a former Norman window opening left of the 19th century window can be seen on the inside of the wall. There is the west jamb of another Norman window farther to the right, also visible on the inside wall but otherwise removed when the nave wall was truncated to build a transept jamb, and subsequently the south transept. The 19th century window is constructionally similar to the other late 19th century windows in the church: two windows in the south wall of chancel, the west window of the north transept, and the chancel east window. The design of these windows appears to be inspired by the design and constructional detail of the c1300 east windows of the south transept. At far left of the nave wall the lower part of the corner was rebuilt with buttressed masonry when the west tower added in the 15th century. The porch appears to be Norman and retains simple jambs and impost stones of a Norman doorway. However, it is clear that its gable end was rebuilt at some time to enable the head of the doorway to be heightened, the original round Norman arch reconfigured to become a more fashionable pointed arch. Fortunately, the inner Norman doorway (nave south doorway) survives intact. This is much simpler than the doorways at St Germans, Kilkhampton and Morwenstow but it survives in pristine condition, presumably the result of having had the protection of a porch for most, if not all of its life. However, the doorway has some anomalies, but consistent with Norman design practice. The round-arched doorway has nook shafts to the jambs (one round and the other octagonal) and moulded impost stones, each one different. The moulded bases of the nook shafts are also different to each other. The roundarched head consists of two orders neither of which is moulded or carved, the outer order made of shaped stones of equal thickness and the inner order wedge-shaped voussoirs. At the sides of the porch are simple stone rubble seats with slate slab tops. The south transept is longer than the north transept. Its west wall has no openings except for blocked putlog holes, and no evidence for extension as suggested by Sedding. The south wall has a central late medieval style window (described as being ‘modern’ by Sedding) inserted to a slightly altered 13th century opening with a round relieving arch. The gable is stepped back from the wall face below (like the diminishing stages of a tower) and rises from a dressed weathering like that of the west tower. It is likely that the gable was rebuilt in the 15th century when the tower was built. The upper part of the east and west walls has also been rebuilt. The east wall has two late 13th century windows that are original to the transept. The windows have trefoil-headed lights set back with trefoil-headed outer frames. The window heads are cut from single pieces of stone almost filling the spaces under round relieving arches. The arched form of these relieving arches is one of the reasons that this aisle has previously been considered to be 12th century. Another reason for this misinterpretation is the angled masonry in the corner between the south transept and the chancel, wrongly thought to be evidence for a former crossing tower but it is really the outer walling of a squint (see also Plan). Central to the south wall of the chancel there is the round head of a single-light Norman window made out of one piece of stone. The lower part of the window was lost when a priest’s doorway was added to its left, possibly early in the 16th century when the rood screen was introduced. This doorway was subsequently blocked in; the evidence for this is best seen on the inside of the wall. Late 19th century windows at left and right replace probable late medieval windows that in turn had replaced original Norman windows. The rubble masonry adjacent to the jambs has been rebuilt. The present windows have trefoil-heads like the 13th century windows in the east wall of the south transept but have the extra embellishment of trefoil tracery. Under the right-hand window is the chamfered sill of a probable Norman single-light window. Most of the east wall of the chancel was rebuilt in the late 19th century to a reduced thickness. Most of the stonework was newly quarried at this time but old rubble facing masonry has been used relating to the gable copings. Within the late-19th stonework, both externally and internally, are some re-used chamfered granite fragments. The gable coping rests on kneeler stones that are re-used paired Norman window heads. These are used inverted, and chamfered underneath for their new location. It is possible that these are from 2-light windows that once existed at the east and west ends of the church. The 3-light east window is late 19th century in the style of a late 13th century window with stepped trefoil-headed lights. The walling of the north chapel blends into the old walling of the chancel with no sign of a straight joint. However, there is indisputable evidence for it being a slightly later 12 th century addition to the chancel in the form of the surviving chancel single-light (originally external) north window that is visible from within the chapel and from within the chancel. There were originally probably three windows in the north wall of the chancel and three windows to the south wall. The walls of the chapel have a pronounced batter, a serious precaution against leaning outwards at some later date. The east wall of the chapel has an original single-light Norman window, its round head cut from a single piece of stone like the other Norman windows in this building. A single-light window in the north gable end of the chapel is also Norman. It is made from four pieces of stone. Above window-head level at left and right are blocked putlog holes. There was disturbance to the masonry on the inside of this wall when a fireplace was inserted in the late 19th century, also the wall top was rebuilt when the chimney was added and the roof renewed. The lean-to vestry between the chapel and the north transept also has a Norman window with a monolith head. This is probably re-used from the north wall of the chancel after a wide doorway was created between the chancel and the vestry. The north transept is a 13th century addition to the original Norman church. The date of the transept is based on its original 3-light east window of stepped lancets. The rubble relieving arch relates most to the central light but there are other stones that are angled at either side, spreading the weight of the wall above. There is no sign of disturbance to this window on the inside except for where a lamp bracket and small wall monument have been added to the north jamb. Also there is compelling evidence for the addition of the transept on the inside (see Interior). The upper part of the wall was rebuilt when the transept was re-roofed. The granite 2-light north window of the transept is a 15th century insertion to an original 13th century opening. This window has trefoil-headed lights and an irregular quatrefoil as tracery. The pointed-arched hood-mould is constructed from irregular pieces of stone, possibly reused eroded tracery fragments. The upper part of the gable and the right-hand corner were rebuilt in the late 19th century. The west wall of the north transept was entirely rebuilt in the late 19th century and the northwest corner reconstructed from original quoin masonry. The 3-light west window is also of this date and in the style of a 13th century stepped lancet window. The north wall of the nave has two Norman windows in-situ at either side of a porch that protects the original Norman north doorway. This is a more complete arrangement than that surviving to the south wall. What is missing in both cases is a further window to the west that would have existed in the Norman nave before the walls were truncated at the west end to make wide openings prior to the construction of transepts. At the far left of the north wall of the nave is the other one of only two granite windows in the building. This is a 2-light 15th century window, stylistically very similar to the north window inserted to the north transept. With the virtual absence of granite elsewhere in the building it is quite possible that both granite windows are re-used from elsewhere at some earlier ‘restoration’ of the building. The north porch is something of a mystery. Its presumed date is 17th century based on its round-arched doorway. It is much smaller than the south porch and does not have the same look of antiquity. It is likely that there was formerly a Norman porch and this would help to explain the good condition of the Norman doorway in the north wall of the nave. This doorway (not inspected during the fieldwork for this description) is plain compared to the south doorway, denoting its lower status, not a difference in date. Ancient iron hinges re-used on the present 19th century door are considered to be 13th century and perhaps the oldest example of medieval ironwork in Cornwall. The embattled 3-stage tower is a very simple structure but nevertheless makes a strong architectural statement due to its more vernacular qualities. These include the quality of its stonework and the way that it weathers between the stages, the corbelled battlements and an octagonal stair turret that rises from a square base blended with the Norman stonework of the north wall of the nave. The tower has a pointed-arched west doorway under a rounded 2centred hood-mould and relieving arch. Above the doorway is and an early Perpendicular window. The upper stage has 2-light windows with trefoil-headed lights and sunk spandrels under square hood-moulds. These windows look much later in date but all are original to the tower. It is possible that the tower took a long time to build and that architectural fashion had changed by the time of its completion. Interior The internal walls have been stripped of plaster as a desperate measure to alleviate damp. Lime-wash now covers the bare stonework so that the most of the diagnostic features that became visible when the walls were bare are still discernable. The whole building was reroofed in the late 19th century and now has arched braced trusses. The most interesting parts of the building are the features that survive from the 12 th and 13th centuries. The nave walls are 12th century including a short length of wall on either side of the tower arch. In the south wall of the nave west of the south doorway is the deep embrasure of a 12th century window. There are two similar deeply splayed original window openings in the north wall equally-spaced on either side of the north doorway. Both the south doorway and the north doorway are Norman, the south doorway taller. On either side of a wide inserted window opening east of the south doorway there are the remains of two further Norman window openings, the one to the west of the large opening with part of its arched head, the other window with just its west jamb masonry (seen clearly splayed within the wall as inspected when the walls were stripped of their plaster) very close to the west end of the nave walling where it was made good after the removal of a significant length of wall to make an opening for the south transept. A Norman impost stone partway up this wall is one of the features that have led to speculation about the former existence of a Norman crossing tower. It is likely that the walling was removed and made good long before the transepts were constructed and this detail is simply part of a planned support for a transept arch that was never completed, though there is reference to pointed arches being removed in the late 19th century. In the opposite corner of the crossing, in the walling of the junction between the remains of the nave wall at its east end and the north transept, is the remains of a greenstone block that may have projected in a similar way to the impost stone already described. Here there is very clear evidence of truncation of the nave wall at the east side of the opening to the transept and making good with dressed masonry prior to the addition of the north transept. North of this dressed masonry is evidence for another former feature, possibly a rood stair doorway. The other two corners of the crossing have been too altered since the addition of the transepts to identify whether there were also impost stones in these locations. The south-east corner was altered to accommodate a squint and the large pier of crude rubble masonry that now abuts the springing masonry of the chancel arch was added probably in the 19th century. In the opposite corner the walling has been much more rebuilt as a result of fitting the present nave window so close to the corner. Apart from the splayed masonry surviving low down the outside angle the only clue to the feature that must have preceded this is a straight joint low down at the east end of the surviving nave wall west of the crossing, clearly seen when the walls were stripped of their plaster as the remains of a splayed feature. Either the wall was splayed to its full height to gain better visual access between the nave and transept or that there was another squint here as also suggested by the remains of splayed masonry on the outside bridging the angle. Before the existence of this feature it is likely that there was an impost stone partway up the wall like the one in the opposite side of the nave. In fact it is likely that there were once similar imposts in each corner of the crossing, fitted when openings were cut into the north and south walls of the nave in preparation for the addition of transepts but these were not built until much later and at two different dates and to different lengths. The pointed chancel arch is a late 19th century construction. It is well built and may incorporate masonry from a former Norman arch. It springs from Norman capitals with chevron and other carved detail. At the north side of the chancel, at the opening to the vestry, is another pointed arch, probably built at the same and springing from masonry tied in with the chancel arch. Farther to the right (east) of the north wall is a late 19th century granite doorway, with shouldered head, in the location of the original 12th century doorway that was cut through the north wall of the chancel to give access to the later 12th century chapel addition. The original recess for the Norman door to open into survives in the west wall of the chapel. At far right of the north wall of the chancel is a Norman window opening that was made redundant when the chapel was added. The east wall of the chancel was almost totally rebuilt in the late 19th century. The Norman south wall is rich in evidence and features. In the centre is a Norman window opening, internally much more complete than on the outside but partly the result of the restoration of at least the right-hand jamb since the opening to the right of the window was blocked. This opening now displays the outline of all but part of the head of a former priest’s doorway. Larger windows at left and right have late medieval chamfered rear arches. Breaking into the left-hand window opening and pre-dating it is a tomb niche with a moulded pointed-arched head, possibly 14th century. At far left is a trefoil-headed piscina, possibly 13th century but may be 14th century like the tomb niche. At far right adjoining the masonry relating to the chancel arch is a surviving jamb of the former squint that once visually linked the south transept with the chancel. The north chapel is of great interest as a chapel of such early date in a relatively small parish church. It is also virtually complete almost to eaves and verge level. In front of the east window is a probable original stone rubble altar. In the north wall is a late 19th century granite fireplace with a trefoil-headed arch. Fitting this fireplace and its flue involved cutting away part of the north wall including the left-hand side of the original window jamb prior to making good the rubble walling. The north transept has a stone altar against its east window and the left hand jamb has been partly cut away to fit a stone candle bracket. The north window has a late medieval rear arch. Above this is the upper part of a blocked presumed original 13th century window opening, curiously with a round-arched head. It is possible that the original north window of the nave that was removed with the walling that was demolished to make the opening for the chancel was re-used in the north wall of the chancel, like the re-used window in the vestry. The west wall is a late 19th century rebuild. The south transept has a stone bench to the south and west sides and returned a little way against the east wall. There is a modern altar against the east window nearer the crossing but is unlikely to have been built as a chantry chapel with two east windows. The rubble stonework of the south window opening has been trimmed back to fit the present window. Interestingly, like the original north window of the north transept, this window opening has a round-arched head. Perhaps the former window was a re-used Norman window that became available when the south wall of the nave relating to the added transept was removed. There is memorial glass in the chancel windows, the large window in the nave and in the windows of the north transept. Fittings An inscribed Roman stone has been re-sited (from the church stile) against the south wall of the south transept. The reassembled Norman font has a round bowl over a central turned shaft and carved heads over octagonal corner shafts set at an angle. The early 16th century oak rood screen is original up to impost level, the arches above a simple reconstruction with no canopy. Its design is more restrained than where there are remains of other screens in Cornwall but appropriate to the simple nature of the church. The reredos is made up from early 16th century carved bench ends and other old carved woodwork. There are two carved early 17th century chairs. The octagonal pulpit with fielded panels is probably made from 18th century box pews. It stands on a late 19th century granite base. The lectern is made from carved late medieval fragments. The pews are late 19th century in simple Gothic style. Context Tintagel’s church is remote from the village and set in a very prominent promontory on the north coast, closer to the medieval castle than to the village. The only building near the church is a probable stable built into the churchyard wall adjacent to its entrance gateway. This remoteness, an open landscape, and the sea beyond, and the character of its simple slate chest tombs south of the building make a dramatic frame for the church. The church itself partly due to its lowly scale, and also due to its construction of local materials, appears to grow out of its landscape. Discussion Interpretation of the phasing of the church is very complex. It has been generally argued that the transepts are Norman like the nave and chancel. However, the evidence for their addition to the building is overwhelming. There is no evidence in the fabric of the south transept to demonstrate that this has been lengthened as has been usually stated, or that its east windows have been inserted. The east windows of the transepts are original and undisturbed within their associated wall masonry and their architectural detail determines the date of each transept, each one a different 13th century date. There is no evidence for a former crossing tower. The splayed masonry relating to the transepts relates to squint features. The surviving impost stones survive from an intermediate phase when sections of the north and south walls of the nave were taken down in preparation for the proposed crossing. The transepts were not built until later. It is likely that there was temporary timber framing filling the openings for a time until funds could be raised to build the transepts. However, it is puzzling that the north and south windows of the transepts have round heads. A probable explanation for this is that when the transepts were built, the Norman windows that had been previously removed were re-used in the end walls of the transepts both for economy and to provide visual uniformity to the building as seen from the north or from the south at this time. Despite revised interpretation the Church of St Materiana is still the best Norman parish church in Cornwall. The survival of both Norman doorways and a high proportion of its original windows are unparalleled. The south porch is of uncertain date but most likely Norman, and possible original to the building. The north chapel is an extraordinary building, unique in Cornwall, not for its plan position but on account of its simple design and its walls built to such a pronounced batter.