Will IT security founder on the reef of human behavior

advertisement

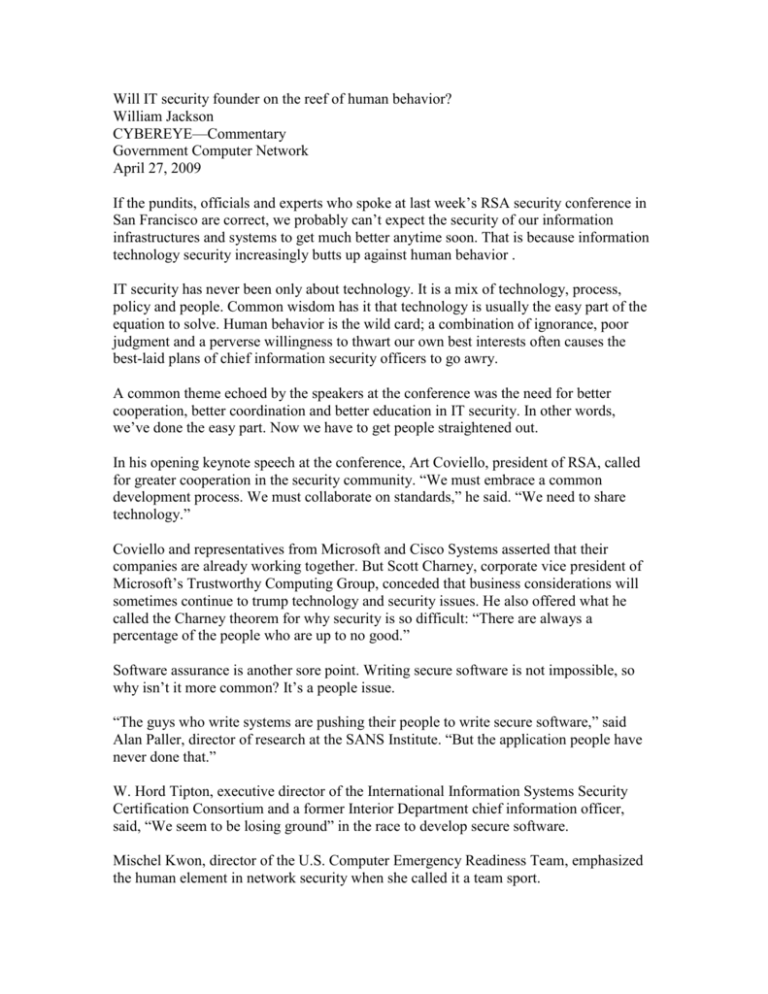

Will IT security founder on the reef of human behavior? William Jackson CYBEREYE—Commentary Government Computer Network April 27, 2009 If the pundits, officials and experts who spoke at last week’s RSA security conference in San Francisco are correct, we probably can’t expect the security of our information infrastructures and systems to get much better anytime soon. That is because information technology security increasingly butts up against human behavior . IT security has never been only about technology. It is a mix of technology, process, policy and people. Common wisdom has it that technology is usually the easy part of the equation to solve. Human behavior is the wild card; a combination of ignorance, poor judgment and a perverse willingness to thwart our own best interests often causes the best-laid plans of chief information security officers to go awry. A common theme echoed by the speakers at the conference was the need for better cooperation, better coordination and better education in IT security. In other words, we’ve done the easy part. Now we have to get people straightened out. In his opening keynote speech at the conference, Art Coviello, president of RSA, called for greater cooperation in the security community. “We must embrace a common development process. We must collaborate on standards,” he said. “We need to share technology.” Coviello and representatives from Microsoft and Cisco Systems asserted that their companies are already working together. But Scott Charney, corporate vice president of Microsoft’s Trustworthy Computing Group, conceded that business considerations will sometimes continue to trump technology and security issues. He also offered what he called the Charney theorem for why security is so difficult: “There are always a percentage of the people who are up to no good.” Software assurance is another sore point. Writing secure software is not impossible, so why isn’t it more common? It’s a people issue. “The guys who write systems are pushing their people to write secure software,” said Alan Paller, director of research at the SANS Institute. “But the application people have never done that.” W. Hord Tipton, executive director of the International Information Systems Security Certification Consortium and a former Interior Department chief information officer, said, “We seem to be losing ground” in the race to develop secure software. Mischel Kwon, director of the U.S. Computer Emergency Readiness Team, emphasized the human element in network security when she called it a team sport. “We have to stop isolating ourselves as security experts,” she said. “Our adversaries are collaborating. They are working together.” The human element even inhibits the interoperability of security tools, said Richard George, technology director of the National Security Agency’s Information Assurance Directorate. “We have a history of making things that are supposed to work together not work together,” he said. William Billings, chief security officer at Microsoft Federal, said many security tools are interoperable and administrators need to differentiate between technology issues and training issues. “The hard part is how to get the IT staff to pull the data out,” he said. That is not to say that there are no technology issues to be resolved in IT security. Many problems remain, and there will always be a need to find and fix them. But the experts seem to think that security technology has outpaced the ability or willingness of people to use it. Without some significant changes in the way vendors, administrators and users think about IT security, improvements are likely to be marginal, and we will continue to lose ground against the bad guys, who are free to focus on the soft underbelly of human behavior when attacking our systems.