chapter 18 – answers to questions in text

advertisement

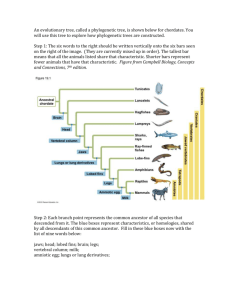

R.M. Clary, Ph.D., F.G.S. Department of Geosciences Mississippi State University CHAPTER 18 LIFE OF THE CENOZOIC ERA OUTLINE INTRODUCTION MARINE INVERTEBRATES AND PHYTOPLANKTON PERSPECTIVE The Messel Pit Fossil Site in Germany CENOZOIC VEGETATION AND CLIMATE CENOZOIC BIRDS THE AGE OF MAMMALS BEGINS Monotremes and Marsupial Mammals Diversification of Placental Mammals PALEOGENE AND NEOGENE MAMMALS Small Mammals—Insectivores, Rodents, Rabbits, and Bats A Brief History of the Primates The Meat Eaters – Carnivorous Mammals The Ungulates or Hoofed Mammals Giant Land-Dwelling Mammals—Elephants Giant Aquatic Mammals—Whales PLEISTOCENE FAUNAS Ice Age Mammals Pleistocene Extinctions INTERCONTINENTAL MIGRATIONS SUMMARY CHAPTER OBJECTIVES The following content objectives are presented in Chapter 18: Survivors of the Mesozoic extinctions evolved and gave rise to the present-day invertebrate marine fauna. Angiosperms continued to diversify and to dominate land plant communities, but seedless vascular plants and gymnosperms are still common. Many of today’s families and genera of birds evolved, and large flightless birds were important Early Cenozoic predators. If we could visit the Paleocene, we would not recognize many of the mammals, but more familiar ones evolved during the following epochs. Small mammals such as rodents, rabbits, insectivores, and bats adapted to the microhabitats unavailable to large mammals. 171 R.M. Clary, Ph.D., F.G.S. Department of Geosciences Mississippi State University Carnivorous mammal fossils are not as common as those of herbivores, but there are enough to show their evolutionary trends and relationships to one another. The evolutionary histories of odd-toed and even-toed hoofed mammals are well documented by fossils. Today’s giant land mammals (elephants) and giant marine mammals (whales) evolved from small Early Cenozoic ancestors. Extinctions at the end of the Pleistocene Epoch were most severe in the Americas and Australia, and the animals most affected were large land-dwelling mammals. As Pangaea continued to fragment during the Cenozoic, intercontinental migrations became increasingly difficult. A Late Cenozoic land connection formed between North and South America, resulting in migrations in both directions. LEARNING OBJECTIVES To exhibit mastery of this chapter, students should be able to demonstrate comprehension of the following: the composition of Cenozoic marine invertebrate communities the distribution of Paleogene and Neogene vegetation and its climatic significance the continuing evolution of birds the diversification of mammals, especially placental mammals the nature of archaic Paleocene-Eocene mammalian faunas compared to those of the later Cenozoic adaptive radiation and evolutionary trends in hoofed animals the significance of gigantism in Pleistocene mammals the distribution of mammals as related to plate tectonics the hypotheses for the Pleistocene extinction event CHAPTER SUMMARY 1. The marine invertebrate groups that survived the Mesozoic extinctions diversified throughout the Cenozoic. Bivalves, gastropods, corals, and several kinds of phytoplankton such as foraminifera proliferated. Figure 18.1 Restoration of Fossils from the Eocene-aged Clarno Formation in John Day Fossil Beds National Monument, Oregon Figure 18.2 Miocene Diatomite and Diatoms Figure 18.3 Cenozoic Foraminifera Figure 18.4 Cenozoic Fossil Invertebrates 172 R.M. Clary, Ph.D., F.G.S. Department of Geosciences Mississippi State University 2. During much of the Early Cenozoic, North America was covered by subtropical and tropical forests, but the climate became drier by Oligocene and Miocene time, especially in the midcontinent region. Figure 18.5 Cenozoic Vegetation and Climate 3. Birds belonging to living orders and families evolved during the Paleogene Period. Large, flightless predatory birds of the Paleogene were eventually replaced by mammalian predators. Figure 18.6 Restoration of Diatryma Enrichment Topic 1. Shorebird Population in Rapid Decline. Since records have been kept of bird populations, 20% of species have gone extinct. In March 2008, a 24-year survey reported the decline in Australian and Asian shorebirds, beginning in the mid-1980s. Migratory shorebirds of Australia dropped to 73%, while resident Australian shorebirds had been reduced to 81%. Wetland loss from damming and river diversion is partly responsible for decline. Wright, “Shorebird Population in Rapid Decline,” Discover, January 2009, p. 42-43. 4. Evolutionary history is better known for mammals than for other classes of vertebrates, because mammals have a good fossil record and their teeth are so distinctive. Enrichment Topic 2. Vertebrates and Tectonics Paleobiologist Malcolm McKenna proposed a proto-Iceland that once connected North America to Europe, 56 million years ago. While most researchers acknowledge a land bridge between Siberia and Alaska, McKenna proposed that 55 million years ago, it was possible to “walk from New Mexico to Paris, without changing latitude.” This land bridge may have allowed species to migrate between continents, but researchers pointed out that the land bridge would also have blocked circulation between the Arctic and Atlantic oceans. Furthermore, changes in ocean temperature would have occurred when the land bridge broke, which may have led to intense global warming in the PaleoceneEocene boundary. The hypothesis also explains an extinction of benthonic foraminifera. Other geologists question the new hypothesis, however. “Vertebrates and Tectonics,” Geotimes, December 2003, v.48 n.12 p.8-9. 5. Egg-laying mammals (monotremes) and marsupials exist mostly in the Australian region. The placental mammals—by far the most common mammals—owe their success to their method of reproduction. All placental and marsupial mammals descended from shrew-like ancestors that existed from Late Cretaceous to Paleogene time. Figure 18.7 Mammals Existed During the Mesozoic, but Most Placental Mammals Diversified During the Paleocene and Eocene Epochs Figure 18.8 Archaic Mammals of the Paleocene Epoch Figure 18.9 Some of the Earliest Large Mammals Figure 18.10 Pliocene Mammals of the Western North American Grasslands 173 R.M. Clary, Ph.D., F.G.S. Department of Geosciences Mississippi State University 6. Small mammals such as insectivores, rodents, and rabbits occupy the microhabitats unavailable to larger animals. Bats, the only flying mammals, have forelimbs modified into wings but otherwise differ little from their ancestors. Figure 18.11 Fossil Rodents Enrichment Topic 3. Move Over, Ratzilla. A rat skull dating 4 million years old was found in 2008 in Uruguay. This skull belonged to a creature as large as a bull, and as heavy as a small car. The new “champion” rat, Josephoartigasia monesi, lived in forests near river deltas or estuaries. This large vegetarian probably survived until 3 million years ago, when the intercontinental migration brought North American bears and cats into its range. (Dickinson, “Ancient Rat as Big as a Bull,” Discover, January 2009, p. 79. 7. Most carnivorous mammals have well-developed canines and specialized shearing teeth, although some aquatic carnivores such as seals have peglike teeth. Figure 18.12 Teeth of Carnivorous Mammals Figure 18.13 Today’s Carnivorous Mammals Evolved from a Primitive Group Known as Miacids Enrichment Topic 4. Venomous Mammals? Richard Fox, paleontologist, found some fossils of a 60 million-year-old mammals. The fragments featured a long, pointed canine tooth that resembled venom-delivery structures. In fact, the groove in the canine tooth parallels channels found in some venomous snakes. Few modern mammals are known for venoms: Only the two species of solenodons living in Haiti and Cuba have grooves in their teeth for venom delivery. Mark Dufton, biochemist, suggested that early mammals may have been limited by their size, and oral venom would have been an asset. “Killer Bite,” Science News, June 25, 2005, v.164 n.20 p.403. 8. The most common ungulates are the even-toed hoofed mammals (artiodactyls) and odd-toed hoofed mammals (perissodactyls), both of which evolved during the Eocene. Many ungulates show evolutionary trends such as molarization of the premolars as well as lengthening of the legs for speed. Figure 18.14 Characteristics and Evolutionary Trends in Hoofed Mammals 9. During the Paleogene, perissodactyls were more common than artiodactyls but now their 16 living species constitute less than 10% of the world’s hoofed mammal fauna. Figure 18.15 Relationships among the Artiodactyls (Even-Toed Hoofed Mammals) 10. Although present-day Equus differs considerably from the oldest known member of the horse family, Hyracotherium, an excellent fossil record shows a continuous series of animals linking the two. Figure 18.16 Evolution of Horses Table 18.1 Trends in the Cenozoic Evolution of the Present-Day Horse Equus 174 R.M. Clary, Ph.D., F.G.S. Department of Geosciences Mississippi State University 11. Even though horses, rhinoceroses, tapirs, as well as the extinct titanotheres and chalicotheres, do not closely resemble one another, fossils show they diverged from a common ancestor during the Eocene. 12. During much of the Cenozoic Era, proboscideans of one kind or another were widespread on northern continents, but now only three species exist. Figure 18.17 Phylogeny of Elephants and Some of Their Relatives 13. The fossil record for whales is now complete enough to verify that they evolved from land-dwelling ancestors. Figure 18.18 Relationships among Whales and Their Land-Dwelling Ancestors Enrichment Topic 5. From Where the Whale? Paleontologists look at the skeletal morphology of modern organisms and ancient fossils to find similarities and differences. Molecular biologists look at genes to see how many the modern and fossil organism had in common. Until recently these two groups had very different answers for the ancestor of whales. They did agree that cetaceans evolved from four-legged animals that roamed the land, with nostrils near the tips of their noses and teeth of several sizes and types. Cetaceans moved into the sea during the Eocene, almost 50 million years ago. Scientists, however, disagreed on other issues. The paleontologists thought that ancient whales were members of an extinct group of highly-specialized ungulates (hoofed mammals) called mesonychians. Molecular biologists favored artiodactyls (even-toed ungulates such as cows, pigs, camels, deer, and hippos) as the ancestors of cetaceans. Recently discovered complete cetacean fossils, 49 million years old, have brought paleontologists over to the side of the molecular biologists. This peacemaking fossil was wolf-sized Pakicetus attocki, a meat eater, similar to modern dogs but with more a powerful tail, longer snout and smaller eyes. Pakicetus was a landlubber; adapted to walking and running on land, but also may have fed while wading in streams. Pakicetids are thought to be ancestral to cetaceans because of the structure of their ear bones and anklebones. “From Where the Whale?” Oct. 2001, www.studyworksonline.com. Enrichment Topic 6. Blue Whale Ancestor A ferocious fossil whale with sharp, 3 cm long teeth has been found in Australia. The 25 million year fossils are from an early type of baleen whale, although the new fossil discovery did not have baleen. Instead, the whale was a powerful predator that captured its prey, perhaps sharks. The recent discovery has caused the rewriting of baleen whale evolution. In addition to sharp teeth, the whale also had large eyes, suitable for hunting. “Report: Blue Whale Ancestor Was No Gentle Giant,” Reuters, August 2006, http://www.cnn.com/2006/TECH/science/08/16/blue.whale.ancestor.reut/index.html 14. One important evolutionary trend in Pleistocene mammals and some birds was toward gigantism. Many of these large species died out, beginning about 40,000 years ago. Pleistocene mammalian fauna is remarkable in that so many large species existed. 175 R.M. Clary, Ph.D., F.G.S. Department of Geosciences Mississippi State University Horses, camels, elephants, and other mammals spread across the northern continents during the Cenozoic because land connections existed between those landmasses at various times Figure 18.19 The Irish Elk Figure 18.20 Pleistocene Fossils from Florida and California 15. Changes in climate and prehistoric overkill are the two hypotheses explaining Pleistocene extinctions. Enrichment Topic 7. Were Humans Responsible for Mammoth Extinction? Dale Guthrie reported in 2006 that climate shifts were probably responsible for the mammoth extinctions, and not over-hunting by humans. He used radiocarbon dating of bones from bison, moose, and humans that survived the extinction, and bones of mammoth and wild horses that did not survive. Guthrie stated that radiocarbon dates showed that numbers of bison were actually expanding—before and during human colonization. He concluded that climate shifts were responsible, because they resulted in vegetation changes to which the wild horses and mammoths could not adapt. “Scientist: Humans Not Responsible for Mammoth Extinction,” Reuters, May 13, 2006, http://www.cnn.com/2006/TECH/science/05/10/mammoth.extinction.reut/index.html 16. During most of the Cenozoic, South America was isolated, and its mammal fauna was unique. A land connection was established between the Americas during the Late Cenozoic, and migrations in both directions took place. Figure 18.21 The Great American Interchange Enrichment Topic 8. Did Blond Mammoths Have More Fun? An analysis of 43,000-year-old DNA from prehistoric mammoths indicated that some of them possessed blond fur, a finding that supported previous visual analyses of mammoth hair, which appears to come in a variety of colors. When investigating the DNA, researchers found a key pigmentation gene, Mc1r, which exists in two varieties. When researchers investigated further, they determined that one of the gene versions functioned better than the other for production of brown pigment. The researchers proposed that the weaker gene version produced lighter brown, blonde, or red shades. “Mammoths Get Lighter: DNA Analysis Says There Were Probably Woolly Blondes,” News@Nature.com, July 10, 2006, http://www.nature.com//news/2006/060703-14.html LECTURE SUGGESTIONS Life after the Extinction 1. Discuss how Earth may have appeared when the Cenozoic Era began: Which organisms survived the Mesozoic mass extinction, and which organisms did not? Discuss how the majority of the top terrestrial and marine organisms—in the form of reptiles—were now extinct. 176 R.M. Clary, Ph.D., F.G.S. Department of Geosciences Mississippi State University 2. Why were mammals better equipped to radiate and diversify following the extinction? 3. Did the flying organisms encounter similar extinctions at the end of the Mesozoic? Which flying organisms dominated in the Mesozoic, and which dominate in modern times? 4. Discuss how the marine invertebrate communities changed following the Mesozoic extinction, and compare these changes to those that followed the Paleozoic extinction. In which extinction did marine invertebrates face the greater losses? Evolution of the Horse The evolution of the horse is a great example to review evolution by gradualistic changes. There are several fossil intermediates of the horse. Discuss the evolutionary trends surrounding body size, teeth, elongation of the skull, length of limbs, and number of digits. Why might each of these changes have given the horse an advantage via natural selection? Cope’s Rule 1. Cope’s Rule states that organisms tend to increase in body size over evolutionary time. Have the class investigate when mammals were at their largest sizes. When did some of these larger mammals become extinct? What were the possible reasons for the extinction events? 2. On islands, organisms tend to stay small because of limited natural resources and the competition for these resources. Are there modern examples of smaller life forms on islands that the students can uncover? CONSIDER THIS 1. Is the term “Age of Mammals" a fair assessment of the Cenozoic Era? Is there a better term that should be used? 2. Why do you think the top marine predators of the Mesozoic were reptiles, but they relinquished that role in the Cenozoic? 177 R.M. Clary, Ph.D., F.G.S. Department of Geosciences Mississippi State University IMPORTANT TERMS Artiodactyla browser carnassials Carnivora Cetacea grazer Hyracotherium molar molarization Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum Perissodactyla premolar Primates Proboscidea ruminant ungulate SUGGESTED MEDIA Videos 1. Walking with Prehistoric Beasts, BBC 2. Prehistoric America, BBC 3. Life of Birds by David Attenborough, BBC 4. Life of Mammals, BBC 5. Miracle Planet, Survival of the Fittest, The Science Channel 6. PaleoWorld, Are Rhinos Dinos?, The Learning Channel 7. PaleoWorld, Attack of the Killer Kangaroos, The Learning Channel 8. PaleoWorld, Back to the Seas, The Learning Channel 9. PaleoWorld, Dawn of the Cats, The Learning Channel 10. PaleoWorld, Island of the Giant Rats, The Learning Channel 11. PaleoWorld, Killer Birds, The Learning Channel 12. Life on Earth, The Hunters and the Hunted, BBC 13. Nature: Triumph of Life: The Survivors, PBS Home Video 14. Mammoths of the Ice Age, WGBH Boston 15. Lost Worlds, Vanished Lives, The Rare Glimpses, BBC 16. Life in the Cenozoic, Physical Geography II Demonstration Aids and Slides 1. Evolution of Life on Earth, slide set, Educational Images, Ltd. 2. Cenozoic Fossil Collection, Science Stuff CHAPTER 18 – ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS IN TEXT Multiple Choice Review Questions 1. 2. 3. 4. b a c d 5. 6. 7. 8. b e b c 9. a 10. b 178 R.M. Clary, Ph.D., F.G.S. Department of Geosciences Mississippi State University Short Answer Essay Review Questions 11. South America was isolated from all other landmasses from Late Cretaceous until a land connection with North America formed about 5 million years ago. Before the connection, South American fauna was made up of marsupials and several orders of placental mammals that lived nowhere else. However, when the Isthmus of Panama formed, migrations took place in both directions. As a result of the great American interchange, about 50% of South American’s modern mammals came from the north. 12. As they became grazers, the animals’ teeth became high-crowned and abrasionresistant for chewing grasses. They evolved long, slender limbs as the bones between the wrist and toes and ankles and toes became longer. Their long limbs allowed them to see over grasses and to run fast with greater stride length. Their toes became weight-bearing. 13. Western North America has rocks of the right ages for fossil mammals but eastern rocks are predominantly older. 14. Large leaves with smooth, entire margins characterize rainy, warm climates, while small leaves with incised margins typify cooler, drier regions 15. In the early Cenozoic, one of the early adaptations in birds was the evolution of large, flightless predators such as Diatryma, which stood more than 2 meters tall. These early predators were widespread in North America and Europe during the Paleogene, and in South America they were the dominant predators until about 25 million years ago. Eventually they died out and were replaced by carnivorous mammals. 16. The three trends in whale evolution are (a) increase in body size, (b) modification of the front limbs to paddlelike flippers, and loss of the rear limbs (vestigial organs indicate their former presence and function), and (c) migration of the nostrils to the top of the head. 17. There are four evolutionary trends in horses: (a) a decrease in the number of toes, (b) an increase in size, (c) lengthening of the limbs, and (d) the development of high-crowned teeth with complex chewing surfaces. 18. The Paleocene fossil ferns and palms in the western interior of North America indicate a warm, subtropical climate. About 55 million years ago a large scale oceanic circulation was disrupted, and an abrupt warming trend took place, known as the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum. Subtropical conditions persisted in the Eocene, probably the warmest of all Cenozoic epochs. A major climate change took place at the end of the Eocene, when mean annual temperatures dropped as much as 7oC in 3 million years. A general decrease in precipitation during the last 25 million years took place in the mid-continent of North American, and the vast forests of the Oligocene gave way to savannah conditions, then steppe conditions. 179 R.M. Clary, Ph.D., F.G.S. Department of Geosciences Mississippi State University Our Pleistocene Ice Age ended about 10,000 years ago, and temperatures have risen since then. 19. The Paleocene fauna are considered archaic because, although several orders of mammals were present, some were simply holdovers from the Mesozoic or belonged to new, but short-lived groups that have no living descendants. 20. Although dogs and hyenas are similar in appearance and are pack hunters, they are only distantly related. Hyenas are more closely related to cats and mongooses and their similarity to dogs is because of convergent evolution. Apply Your Knowledge 1. One anomalous feature of this assemblage of fossils is the number of carnivores. With endothermic animals, the ratio of predator to prey is a low number (usually less than 5%), because endothermic animals have a large energy requirement. “Several” horses, camels, and mastodons would not be enough animals to sustain “dozens” of saber-toothed cats, dogs, and vultures (all predators). The organic mudstones and claystones indicate a shallow environment, perhaps a swampy area. If large animals came to this paleoenvironment to drink, they might have become mired or trapped in the area. Trapped animals and decaying carcasses would attract predators to the site, and these animals likely became trapped as well. The large occurrence of fossil carnivores is also noted at La Brea Tar Pits in Los Angeles, California, where a similar scenario likely played out in the Pleistocene. 2. Carnivorous mammals can be identified by their specialized shearing teeth, or carnassials, and sharp pointed canine teeth. In herbivorous mammals, the canines are not well developed, but instead the teeth show molarization to provide a continuous row of grinding teeth. Grazers, or animals that eat grass, evolved highcrowned cement-covered chewing teeth. Browsers, or animals that ate bushes and shrubs, have molars, but do not have the high-crowned teeth found in grazers. Speedy runners can be detected by the long, slender limb bones. As hoofed mammals evolved for speed, the bones between the wrist and toes and the ankle and toes became longer. In contrast, mammals such as rhinoceroses have sturdy limb bones to support their large weight. Plant fossils can be used to indicate ancient climates. The smaller leaves with incised margins are more indicative of cooler, drier areas, while leaves with entire or smooth margins and drip-tips dominate in areas with abundant rainfall and high annual temperatures. 3. Student answers will vary greatly. Example: The first vertebrates to evolve were fish. Eventually, fish with articulating bones in their fins evolved to survive in swampy environments. From these fish, limbs evolved via natural selection, and amphibians eventually moved onto the land. However, these amphibians, just like the frogs we have today, had to return to the water to lay their eggs. 180 R.M. Clary, Ph.D., F.G.S. Department of Geosciences Mississippi State University When reptiles evolved from amphibians, they had tough skin and were able to reproduce with shelled eggs. They did not need to return to the water to reproduce. From early reptiles, a group of mammal-like reptiles evolved before the dinosaurs. Although mammals did co-exist with dinosaurs, they did not dominate their area until the dinosaurs went extinct. Then, the mammals that survived the extinction rapidly diversified to fill the different environments on Earth. 4. Student answers will vary. Data that would help resolve the overkill hypothesis might include the discovery of large deposits of butchered extinct animals’ bones, whose dates would coincide with the extinction of these organisms. Conversely, if large deposits of extinct animals’ bones were found in areas with no signs of human habitation, then scientists would have to rethink the overkill hypothesis. Data that would support or refute the climate change hypothesis might be more difficult, because climate changes would affect more organisms, instead of a selective group (large North and South American mammals). If faunal and floral data could show that the continents most affected by extinction had a more severe climate change, this would support the hypothesis. Conversely, if data show that the climate fluctuations on the continents most affected by the extinctions were milder, this would help to refute the climate change hypothesis. 181