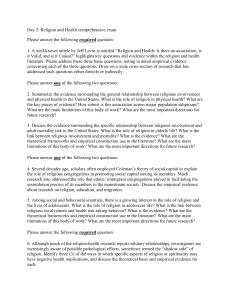

DAVIDSON`S DANGEROUS IDEA

advertisement

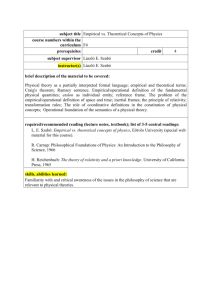

DAVIDSON’S DANGEROUS IDEA Davidson, ‘The Myth of the Subjective’ Subjectivism (empiricism): The mind has private objects before it which: (i) the mind passively receives from the world (such as sense data) and (ii) serves to justify empirical knowledge. This picture of the mind motivates two doctrines that have defined the problems of modern philosophy: Scheme/content dualism: there are ultimate sources of evidence (such as sense data), which can be specified independently of any empirical theory and serves to justify our empirical theories. Foundationalism: Thus, the authority of this ultimate source of evidence is guaranteed, and it can therefore serve as a foundation for empirical knowledge. Rejecting subjectivism can be seen as combining two rejections, the rejection of the myth of the given the rejection of the analytic/synthetic distinction and applying this synthesis to epistemology and the philosophy of mind. Sellars against the Myth of the Given The Myth Given is the idea that there is a sort of awareness such that being in that state of awareness entails both: that one has a certain sort of knowledge, if only knowledge of being in that state of awareness, purely in virtue of being in that state of awareness, and that being in this state of awareness is independent of having concepts, and so it is independent of having a language. Sellars maintains that these properties are incompatible: only that which has content (and so conceptual) can justify a belief; correlatively, only that which has content (and so conceptual) can stand in need of justification: ‘The essential point is that in characterizing an episode or a state as that of knowing, we are not giving an empirical description of that episode or state; we are placing it in the logical space of reasons, of justifying and being able to justify what one says’ (‘Empiricism and the Philosophy of Mind’, §36). Sellars draws the conclusion that ‘the idea that the epistemic facts can be analyzed without remainder—even “in principle”—into non-epistemic facts, whether phenomenal or behavioural, public or private, with no matter how lavish a sprinkling of subjunctives and hypotheticals is, I believe, a radical mistake—a mistake of a piece with the so-called “naturalistic fallacy” in ethics’ (§5). It does not make sense, then, to try to give a foundation to empirical knowledge: ‘For empirical knowledge, like its sophisticated extension, science, is rational, not because it has a foundation but because it is a self-correcting enterprise which can put any claim in jeopardy, though not all at once (§38). Quine against the Analytic/Synthetic Distinction Experience confirms or disconfirms theories, rather than individual statements: ‘our statements about the external world face the tribunal of sense experience not individually but only as a corporate body’ (‘Two Dogmas of Empiricism’, p. 41). Statements cannot be analysed as having a linguistic component and a factual component: ‘it is nonsense, and the root of much nonsense, to speak of a linguistic component and a factual component in the truth of any individual statement’ (p. 42). Theories, rather than individual statements, are units of meaning: ‘The unit of empirical significance is the whole of science’ (p. 42). No statement is immune to revision: ‘Any statement can be held true come what may, if we make drastic enough adjustments elsewhere in the system. . Conversely, by the same token, no statement is immune to revision’ (p. 43). 2 Davidson’s Antisubjectivism Founding Insight: Semantic externalism We learn the meaning of a word through a conditioning process that links words to objects in the world. Thus, the meaning of a word is what typically causes utterances of it. Now if the meaning of a sentence is determined by the meanings of its parts, the words which compose it, then the meaning of a sentence cannot be subjective: it must be determined by the world. Consequences Davidson draws from semantic externalism Cartesian scepticism cannot be formulated ‘since the senses and their deliverances play no central theoretical role in the account to of belief, meaning, and knowledge if the contents of the mind depend on the causal relations, whatever they may be, between the attitudes and the world’ (p. 45) Rejection of scheme/content dualism ‘certain beliefs caused by sensory experience are often veridical, and therefore often provide good reasons for further beliefs’ (p. 45) Rejection of the intelligibility of conceptual relativism Conceptual relativism: There may be incommensurable conceptual schemes. Conceptual scheme: A way of organising empirical content. Empirical content: the facts, the world, experience, sensation, the totality of sensory stimuli, etc. Rejection of the need for a foundation for empirical knowledge ‘although sensation plays a crucial role in the causal process that connects beliefs with the world, it is a mistake to think it plays an epistemological role in determining the contents of those beliefs. In accepting this conclusion, we abandon the key dogma of empiricism, what I have called the third dogma of empiricism. But that is to be expected: empiricism is the view that the subjective (‘experience’) is the foundation of objective empirical knowledge. I am suggesting that empirical knowledge has no epistemological foundation, and needs none’ (p. 46). 3 Is the study of perception central to the study of knowledge? Strawson: ‘Ayer has always give the problem of perception a central place in his thinking. Reasonably so; for a philosopher’s views on this question are a key both to his theory of knowledge in general and to his metaphysics’ (‘Perception and its Objects’, in MacDonald (ed), Perception and Identity, p. 40). Davidson: ‘If this is right, epistemology (as apart, perhaps from the study of perception, which is now seen to be only distantly related to epistemology) has no basic need for purely private, subjective ‘objects of the mind’, either as uninterpreted sense data or experience on the one hand, or as fully interpreted propositions on the other. . . There is an abundance of puzzles about sensation and perception, but these puzzles are not, as I said, foundational for epistemology’ (‘The Myth of the Subjective’, p. 46). 4