Gray_Mittell_Checked..

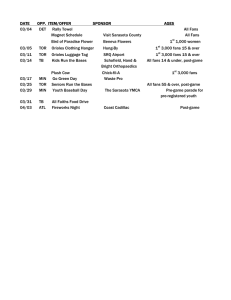

advertisement