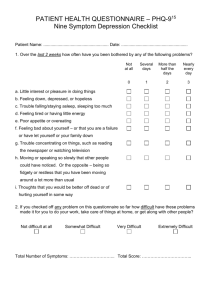

using a personal questionnaire approach to identifying

advertisement