Trigger Events in Cross-Cultural Sensemaking

advertisement

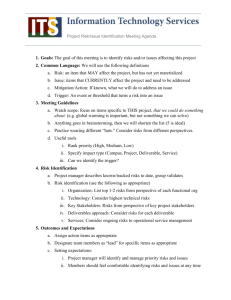

Trigger Event 2/16/2016 TRIGGER EVENTS IN INTERCULTURAL SENSEMAKING Joyce Osland San Jose State Unviersity Allan Bird University of Missouri-St. Louis & Allison Gundersen Case Western Reserve University ABSTRACT In a global economy intercultural adaptability is an important skill for anyone working across cultures. We adopt a social cognitive approach to explain trigger events – occasions that lead people to notice cultural differences – which in turn generate opportunities for intercultural sensemaking. Because the trigger event construct has received little attention and scant empirical study since its conception, we performed a multidisciplinary review of trigger event definitions, resulting in an explicated list of characteristics. In a process model, we delineate four moderators of the arousal-attention dynamic as well as threshold moderators of situational characteristics that may constitute triggers leading to intercultural sensemaking. We position trigger events within the larger context of intercultural adaptation and effectiveness. 2 TRIGGER EVENTS IN INTERCULTURAL SENSEMAKING The range of what we think and do Is limited by what we fail to notice. And because we fail to notice That we fail to notice, There is little we can do To change Until we notice How failing to notice Shapes our thoughts and deeds. - R.D. Laing An American was on a short-term assignment in Germany, a country with which he had little personal experience. As he rode the bus or walked through the streets, he was surprised that people ignored the nods and smiles he sent in their direction. Although he didn’t take their reaction personally, he was both puzzled and uncomfortable by this unexpected behavior. He drew on previous experiences in Japanese culture where people sometimes avoid meeting strangers, thereby avoiding the incurrence of more obligations, but this felt very different. After a while, he asked a trusted German friend to explain the lack of greeting behavior. Since the German had no quick explanation, the American began to quiz him, trying to figure out in what specific situations Germans interact in this manner. He developed a working hypothesis about the development of intimacy in German culture, which he tested out with his German subordinates. Over time, the American also began to see a pattern in other behavioral contexts – for example, the relations between those with authority and those without and the way junior colleagues adjusted their behavior when speaking with senior colleagues. Eventually he saw the lack of greetings to strangers on the street as part of a larger cultural pattern of social distance. Once he understood the pattern, he stopped nodding and smiling, stopped expecting this behavior from others, and ceased to reflect on it. What prompted the American to pause and try to figure out the German behavior he observed? The absence of expected behavior served as a trigger event that initiated a period of focused cultural 3 sensemaking. Recent research into the intercultural adaptability of expatriates has taken a social cognitive approach, focusing specifically on the processes by which managers make sense of culturally different behaviors (Osland & Bird, 2000). However, as Starbuck and Milliken (1988) insightfully point out, “If events are noticed, people make sense of them and if events are not noticed, they are not available for sensemaking” (Starbuck & Milliken, 1988: 60). Our current investigation focuses on “trigger” events in understanding what factors and conditions evoke intercultural sensemaking behaviors and cognitions in intercultural settings. Within the realm of managerial research, the trigger concept has remained largely unaddressed since Louis (1980) and Louis and Sutton’s (1991) seminal work on surprise and sensemaking. Consequently, few organizational scholars have empirically examined the concept or elaborated upon it conceptually. One exception is Maitlis and Lawrence’s (2008) study of conditions that trigger sensegiving in organizations. While some research on intercultural competence has focused more extensively on conditions that prompt mindfulness (cf., Berger & Douglas, 1982; Ting-Toomey, 1999) and the processes surrounding unexpected behavior and their outcomes for people in intercultural interactions (cf., Storti, 1990), it, too, has left the nature of trigger events largely unexplored. Therefore, this topic is important for both theoretical and practical reasons. First, a multidisciplinary review and synthesis of prior work may lead to a clearer conceptualization of trigger events and elaborate multiple facets of the phenomenon. Second, a more thorough understanding of the role of trigger events that incorporates cognitive considerations in intercultural sensemaking and a delineation of the process could contribute to intercultural training and coaching. Accurate cultural sensemaking is an essential element of effective global leadership (Osland, Bird, Osland, & Oddou, 2007). In the next section, we review and synthesize the definitions and treatment of trigger events in various disciplines that utilize this concept. This is followed by an explanation of sensemaking and its 4 distinctive characteristics within the intercultural context. We present a process model of trigger events in intercultural sensemaking and conclude with implications for future research and practice. UNDERSTANDING TRIGGER EVENTS In an organizational context, a trigger event has been defined as an interruption in a cognitive flow (Weick, 1995); however, many disciplines – e.g., chemistry, computer science, operations research, psychology, education, and so forth -- have developed their own definitions of trigger events. For example, in chemistry, a trigger event is characterized by a chemical reaction or phase transition, whereas in education it is defined as a “disorienting dilemma”; in intercultural communication, it is a “culture bump” that indicates unexpected behavior and in computer science, it is a set of rules that identify exceptionality. A multidisciplinary literature review led to the exploration and synthesis of the varied definitions and applications, resulting in the following explication of various trigger event characteristics. Trigger events deviate from expectations. Louis (1980) identified one category of trigger events, describing them as surprises or discrepancies from expected or deliberate initiatives to pay attention because one does not know what to expect (Louis & Sutton, 1991). Archer (1986), for example, coined the term “culture bump” to refer to a cultural difference that causes a disruption in thinking or behavior flow, which is grounded in expectations stemming from the normal situational behavior learned within one’s own culture. Trigger events are disruptions to a stable state that lead to a new state. Trigger events are described as perturbations that are responsible for moving a system from an initial state to a final goal state (Senglaub, 2001). For instance, an automated military training program that models 5 commander’s intent1 uses trigger events to move a system from a starting condition through a series of intermediate states to a final goal state (Senglaub, 2001). Trigger events prompt changes in direction or trajectory. In artificial intelligence, computer science, and engineering, trigger events are rules that identify exceptionality and signal that a change in function is needed. In a similar vein, decision making in operations research views trigger events as changes in environmental circumstances or as new information that activates further decisions and/or alterations in course (Joosten, 1994). For instance, expert schedulers use “'broken-leg' cues as a decision making trigger event, i.e., an event or information that alters the certainty of a standard determinant event” (McKay, Buzacott, Charness & Safayeni, 1992). On an organizational level, triggers events may lead to a change in strategic direction as a response to internal or external stimuli (Walsh & Ungson, 1991). Trigger events initiate previously learned responses. Some trigger events are viewed simply as behavioral or emotional prompts of the stimulus-response variety. As used in social work (Humair & Ward, 1998; Parker & Randall, 1996), trigger events in operant conditioning, are formulated as situations that activate negative behaviors. For example, identifying triggers is often a fundamental component of smoking cessation and addiction programs. Once the trigger-response linkage is understood, the trigger can be eliminated or avoided, or the response behavior can be modified. Trigger events can be multiple. Multiple triggers can occur within the same interactive affective and behavioral incident, especially as humans react and interact with others. For instance, Lewis argues that triggers in emotional sensemaking, what he calls “emotion appraisal,” can define the onset of an emotional episode, as well “as any point in an ongoing appraisal-emotion stream” (Lewis, 2004: 27). For example, in a merger, a female manager from the acquired firm was offended by a 1 Commander’s intent is defined as a concise expression of the purpose of an operation and its desired end state that serves as the initial impetus for the planning process. 6 pushy male executive from the acquiring company. Her forceful response elicited more aggressive behavior on the executive’s part. The initial action and the subsequent responses that marked their escalating conflict and disintegrating relationship constituted multiple trigger events. Triggers, therefore, can modify the ongoing sensemaking, replacing it or extending it, based on the current context and state of the individual (Lewis, 2004). Trigger events can be accumulative. Accumulative trigger events can take two forms. A persistent cue or signal may come to be seen as a disruption, as noted in research on problem detection (Billings, Milburn & Schaalman, 1980). For example, repeated complaints from the same supplier may eventually prompt corrective action. An accumulative trigger may also result from multiple disparate cues in aggregation (Cowan, 1986), such as the employee who ultimately realizes that he should start looking for a new job after observing a series of events: slow promotion decisions that were formerly automatic, buy-out rumors in the press, decreased stock prices, and a superstar employee who jumps ship. Trigger events can be transformative, leading to deeper understanding and higher consciousness. In transformational learning, trigger events are called “disorienting dilemmas” that lead students to self-examination, to critically question their beliefs and assumptions and, eventually, to adopt a new perspective on their experience or the world, moving to a new paradigm (Cranton, 1994; Mezirow, 1991; 1997; 2000). The common thread running through these many definitions and aspects is that a trigger event is an interruption in a previously stable state or coherent flow that initiates a response, leading to a new state. When trigger events involve cognition, that new state may involve sensemaking, learning and, possibly, transformation. 7 THE INTERCULTURAL CONTEXT Trigger events are inextricably linked to context. In the intercultural context, we view culture as a communal response to the need for simplification and uncertainty reduction. Different communities reach different answers to common questions; thus, when people from diverse cultures interact there is a large potential for misunderstanding, for gaps between the expected and the experienced (Bird & Osland, 2006). Culture is a society’s way of addressing basic issues and questions such as what is the nature of the individual; what is the relationship of people to nature; how should relationships within a community be structured; how should time be viewed; and what is the purpose of activity (Brannen et al., 2004; Kluckhohn & Strodtbeck, 1961). The objective in answering these questions is to reduce uncertainty so that through shared understandings -- both tacit and explicit -- the community can function effectively. Weick’s (1979) definition of organizing as a “consensually validated grammar for reducing equivocality through sensible interlocks” aptly applies to culture as well. By means of shared values, attitudes and beliefs, as well as norms, rituals and artifacts, cultures reduce the uncertainty surrounding human interaction within a society. Working within a community where there are shared understandings, individuals can develop expectations regarding how events will unfold, how people will behave and what behaviors are appropriate or efficacious. The cognitive element of culture acquisition is supplemented by a physiological element. Recent brain research has identified mirror neurons – neurons that fire both when a person acts and when a person observes actions performed by another -- that may serve as a vehicle for unconscious culture learning (Blakeslee, 2006). Culture also simplifies interpersonal interactions, thereby reducing the need for conscious cognitive effort. When 8 individuals venture outside their cultural group, they are confronted with a substantial increase in uncertainty, which implies cognitive and emotional demands. “It is the ambiguity of meaning that marks the boundaries of culture (Cohen, 1985: 55) – the boundary is where the ambiguity begins, where managers can no longer be sure of the correctness of their interpretation of what is going on” (Apfelthaler & Karmasin, 1998: 8). Intercultural communication researchers highlight the importance of anxiety and uncertainty reduction in intercultural relations. Although they are not labeled as such, these two factors are described in the literature as both triggers and motivating factors for sensemaking. Two types of uncertainty are present in interactions with strangers (Berger & Calabrese, 1975). The first type refers to uncertainty about the strangers’ attitudes, feelings, beliefs, values, and behavior, which hampers the ability to predict their behavior. The second type of uncertainty concerns explanations for strangers’ behavior. “Whenever we try to figure out why strangers behaved the way they did, we are engaging in explanatory uncertainty reduction. The problem we are addressing is one of reducing the number of possible explanations for the stranger’s behavior to understand it and thus be able to increase our ability to predict their behavior in the future” (Gudykunst & Kim, 1997: 32-33). Because the ability to predict how people make decisions is especially useful in business, uncertainty about what strangers see as plausible goals and the appropriate actions to achieve them within a particular setting can trigger uncertainty reduction efforts. Confronted with uncertainty, people who work with other cultures are trained to be mindful, which is closely related to attention and sensemaking. Mindful communication involves attending to one’s internal assumptions, cognitions, and emotions, and simultaneously attuning to the other’s assumptions, cognitions, and emotions (Ting-Toomey, 1999). It also means learning to see behavior or information in a situation as fresh or novel; viewing a situation from several perspectives; attending 9 to the context and the person exhibiting the behavior; and creating new categories through which new behavior may be understood (Langer, 1997; Thich, 1991). These responses can only be initiated subsequent to a trigger event; thus, mindfulness can be readily conceptualized as an aspect of sensemaking. TRIGGER EVENTS AND INTERCULTURAL SENSEMAKING Sensemaking involves placing stimuli into a framework that enables people “to comprehend, understand, explain, attribute, extrapolate, and predict" (Starbuck & Milliken, 1988: 51). Louis (1980) described the role of sensemaking in newcomer socialization as a thinking process that uses retrospective accounts to explain surprises. Sensemaking can be viewed as a recurring cycle comprised of a sequence of events occurring over time. The cycle begins as individuals form unconscious and conscious anticipations and assumptions, which serve as predictions about future events. Subsequently, individuals experience events that may be discrepant from predictions. Discrepant events or surprises, trigger a need for explanation, or post-diction, and, correspondingly, for a process through which interpretations of discrepancies are developed. Interpretation, or meaning, is attributed to surprises…it is crucial to note that meaning is assigned to surprise as an output of the sense-making process, rather than arising concurrently with the perception or detection of differences (Louis, 1980: 241). Thus, sensemaking is an ongoing activity. Within complex situations people “chop moments out of continuous flows and extract cues from those moments” (Weick, 1995: 43). An interruption to a flow often results in an emotional response when there is arousal in the autonomic nervous system. Emotion typically signals a failed expectation and serves as a warning that attention must be paid to a stimulus. The emotion lasts until individuals find an alternative action that maintains their sense of 10 well being (Berscheid, Gangestad, & Kulaskowski, 1984). When a cue is extracted from the general flow of stimuli, it is “embellished” and linked to a more general idea, most commonly to a similar cue from one’s past (Weick, 1995). Once causal relationships are developed, the sensemaking is encoded into cognitive structures that are referred to as “schemas,” and the behavioral responses are called “scripts” (Sims & Gioia, 1986). The phenomenon of intercultural sensemaking is complex and incorporates interrelated variables. Our goal in building the model found in Figure 1 was a parsimonious but comprehensive representation of reality. The model includes only those essential variables supported by the limited research findings, knowledge of the intercultural context, and pilot interviews. The model is based on the assumption that there are various reactions to trigger events, but we are primarily interested in the intercultural sensemaking reaction. The Trigger Events and Intercultural Sensemaking Model (see Figure 1) consists of the following categories of variables: 1) The Trigger Event results from the interaction between a Person, the Situation, and the arousal-attention aspect of sensemaking 2) which sets off conscious or unconscious Event Reactions; 4) the most transformational and positive reaction is Intercultural Sensemaking, which has 5) numerous cognitive, emotional, and behavioral Consequences. Our primary objective within this article is to explicate the relationship among variables in the Trigger Event category process. Given space limitations and the article’s focus, research propositions are presented only for this portion of the model. ===== Insert Figure 1 here. ===== 11 The arousal-attention dynamic is a reciprocal interaction involving an emotional/physiological reason and a cognitive act of appraisal. Arousal and attention are discussed separately below, but the literature treats them as inextricably connected (Lewis, 2005; Gazzaniga, 2004CITE). Arousal-Attention Arousal can be defined as a physiological and psychological condition involving the autonomic nervous system and various neural systems collectively known as the arousal system. Physiologically, arousal primes people for fight or flight reactions. Psychologically, arousal sets off a rudimentary form of sensemaking (Mandel, 1984; Berscheid, 1983). Arousal has three characteristics: more sensitive to sensory stimuli, more physically active, and react more emotionally (Garey, et al., 2003). Arousal helps regulate consciousness, attention and information processing (Posner & Rothbart, 1998). Bradley and Lang (2000) note that variations in arousal are used as a means of differentiating types of emotion. Indeed, Lewis argues that, “Arousal of bodily systems is also a critical component of emotions, as it is necessary to prepare for and support the behaviors they induce (2005:187).” Emotional stimuli are associated with physiological responses involving body temperature, heart rate, breathing, perspiration and sets of physical actions such as fight or flight behaviors (Lewis, 2005). Reciprocally, bodily changes of the type noted above may in turn evoke emotions (Thayer & Lane, 2000). Emotion, and attendant arousal, is highly influential in determining attention (Bower, 1992; Wells & Matthews, 1994). Derryberry and Tucker (1994) use the term “motivated attention” to emphasize that attention tends to focus on that which is emotionally compelling. Indeed, attention motivated by emotional arousal tends to replace or interrupt the pre-existing attentional frame (Oatley & Johnson-Laird, 1987). Emotion, including arousal, may also lead to a narrowing of attention (Lewis, 2004; Weick, 1995). Lewis comments on the relationship between triggers, arousal and 12 attention when he writes, “Thus, perceptual, emotional, and attentional processes amplify one another (positive feedback) but at the same time begin to tune or constrain each other (negative feedback) (2005: 174).” Attention is the cognitive process of selectively concentrating on one aspect of the environment while ignoring others. Research on attention links it to detection, selection and discrimination of stimuli, as well as allocating of limited processing resources to competing attentional demands (Lewis, 2005). Management of attention involves conscious and unconscious choices about what to scan for, what to monitor and what to ignore (Klein et al., 2005). From a neurobiological standpoint there are a range of attentional activities, reflecting lower- and higher-order attention (Lewis, 2005). For example, attention processes involving orienting and monitoring differ from processes involving directed attention or error detection. In trigger events, arousal and attention appear to be inextricably linked. This link is exhibited in this description of a trigger event incident from one of our pilot interviews: “I was noticing how I was reacting, responding, you know, shifting, reframing, and acting to what he was saying. There were points where I could have easily become very angry. And so, at those points, …. I’m stepping back.” In this instance, her emotional arousal directs attention to other cues in the situation which in turn elicit arousal and, in combination serve as a triggering mechanism. Arousal-Attention Moderators According to Weick (1995), the predispositions and experiences of individuals contribute to their sensitivity and openness to trigger events. Furthermore, “cues are not simply cues but rather social constructions generated by people trying to understand situations (Klein et al, 2004: 17). Thus, the meaning assigned to trigger events is often subjective. With respect to intercultural sensemaking, 13 four categories of individual differences influence the perception of trigger events: expertise, stance, curiosity, and emotional resilience. Expertise. Intercultural competence is “the ability to communicate effectively and appropriately in intercultural situations based on one’s intercultural knowledge, skills, and attitudes” (Deardorff, 2004: 194). It includes self-awareness, motivation, perspective taking, the ability to shift and expand one’s frame of reference (cognitive complexity), behavioral flexibility, interpersonal skills, empathy, cultural sensitivity, and stress management (Deardorff, 2006; Gudykunst, 1994; Paige, 1993). The skill component consists of analyzing, interpreting, relating, listening, observing, comparative thinking and cognitive flexibility (Deardorff, 2006). All these competencies and skills are important in heightening an individual’s arousal and attention in intercultural contexts. People with extensive intercultural experience have previously confronted confusing cultural situations, learned to decode cultural behavior, and develop appropriate goals and behavioral schemas that lead to effectiveness. They have “conscious incompetence” (Howell, 1982), i.e., “they know that that they do not always know.” Consequently, their expertise leads them to pay more attention to situational and self-awareness cues. Howell’s (1982) two-by-two learning model contains two axes: incompetence or competence; and unconscious or conscious. People begin at the unconscious incompetence level, move to conscious incompetence, presumably after a trigger event occurs, and then to conscious competence where they can perform it by concentrating, and finally, to unconscious competence when the skill becomes second nature and requires no conscious thought. We argue that greater expertise will correlate with increased sensitivity and higher levels of arousal and attention. More generally, expert cognition includes a more extensive knowledge base developed by experience and the increased ability to perceive and correctly interpret relevant cues, to recognize 14 patterns, anomalies and typicality, and devise creative solutions (Klein, 1998; Sternberg & Davison, 1994). Sometimes experts find meaning in the absence of events (Christoffersen, Woods & Blike, 2001). When an expected event fails to materialize, this can trigger sensemaking. Expectancies play a large role in determining what events come to be seen as triggers; however, novices are less adept at knowing what to expect. With respect to problem detection, Klein and his colleagues note that “the knowledge and expectancies a person has will determine what counts as a cue and whether it will be noticed” (Klein, Pliske, Crandall & Woods, 2005: 17). For example, on a visit to a new country program, the director of a global development organization saw no carts, which are ubiquitous in similar developing countries. This led him to question why the country lacked an inexpensive system of transportation. Neither the local staff nor the less experienced international staff traveling with him observed this cue (Osland, Bird, Osland & Oddou, 2007). Expertise in this model refers to intercultural competence and experience. Proposition 1: The greater the degree of expertise, the greater the level of arousalattention. Stance. Another term for what Weick called individual predisposition to trigger events is called stance, the orientation a person has to a situation (Chow, Christoffersen, & Woods, 2000). With respect to problem detection, “stance is affected by a person’s level of general alertness, level of suspicion, emotional status and so forth” (Klein et al, 2005: 23). Examples of stance with respect to intercultural situations could include such things as positive regard for foreign people or cultures, or the suspicion that one is being taken advantage of by members of the other culture (Osland, 1995). Another intercultural example of stance is reflected in the taxonomy of mindsets depicting increasing levels of intercultural sensitivity, ranging from extreme ethnocentrism at one end to extreme ethnorelativism -- integrating and incorporating aspects of another culture into one’s self-identity -- at 15 the other (Bennett, 1993). People with ethnorelative mindsets would presumably have a higher probability of arousal-attention. Proposition 2: The nature of the person’s stance will influence the level of arousalattention. Curiosity. Curiosity is defined as the motivation for exploratory behavior (Berlyne, 1960). Exploration refers to all activities concerned with gathering information about the environment. The definition of curiosity is further elaborated as “a recognition, pursuit and intense desire to explore novel, challenging and uncertain events” (Kashdan & Silvia, 2008). According to Langevin (1971), measures of curiosity treat it as either a motivational state with behavioral indices or as a personality trait. Curiosity is a key component of intercultural effectiveness (Black & Gregersen, 1991; Kealey, 1996), as well as global mindset (Levy, Beechler, Taylor & Boyacigiller, 2007) and effective global leadersship (Black, Gregersen & Morrison, 1999). While some people are frustrated by cultural differences, others find them stimulating. Thus, the degree of curiosity can influence whether or not people pay attention to anomalies and disturbances and are motivated to decode them. For instance, one intercultural expert possessed a great deal of fundamental knowledge about a middle-eastern culture; yet her curiosity led her to continue questioning host culture members until she could understand their individual perspectives and discover whether they fit the cultural norm. Proposition 3: The greater the degree of curiosity, the greater the level of arousalattention. Emotional Resilience. Resilience is the capacity to cope with, or recover relatively quickly from, stress (Luthar & Cicchetti, 2000). Studies on resilience and stress-coping often note a connection to positive emotion (cf. Ong, et al., 2006). Consequently, it is more commonly referred to as “emotional resilience” in intercultural contexts (Goldstein & Smith, 1999; Sizoo, et al., 2005). The presence of emotional resilience has been 16 consistently identified as one of the common indicators of intercultural effectiveness, implicitly suggesting that it is positively associated with sensemaking. (Arthur & Bennett, 1995, 1997; Caligiuri, 2000; Kealey, 1996; Ronen, 1989). Weick (1995) notes that high levels of stress lead people to narrow their focal field, thereby reducing what they attend to. In intercultural contexts, emotional resilience appears to moderate the extent to which people are affected by stress, thereby enhancing their ability to cope with arousal and engage in meaningful attention. Proposition 4: The greater the degree of emotional resilience, the greater the level of arousal-attention. Trigger Conditions Louis and Sutton (1991) categorized trigger events into three types of situations in which actors shift to conscious engagement: novelty, discrepancy, and deliberate initiative. Novelty refers to situations that are out of the ordinary, unique, and unfamiliar. Discrepancy refers to situations in which expectations differ from reality and constitute disruptions or unexpected failures. Deliberate initiatives are internal or external requests for a higher level of conscious attention, which occurs when people are questioned or ordered to think or pay attention. Novelty. In the intercultural context, novelty usually involves cultural incidents that come as a surprise. Beforehand, actors have the mindset, “We don’t need to think,” (Howell’s unconscious incompetence) (1982) as shown in the following example. A people-oriented Danish manager was very effective in Denmark. He consulted with his subordinates on major decisions and encouraged open communication channels. When his company sent him to manage the Philippines subsidiary, he employed his participative style of leadership and decision-making. He soon began to notice that his Filipino subordinates were afraid to express any disagreement with him and uncomfortable taking initiative and accepting responsibility. He also learned that he was becoming the target of jokes and 17 had lost his subordinates’ respect. His negative emotional reaction to this news and the novelty of having subordinates reject his leadership style triggered an exploration of differences in what his Danish and Filipino subordinates expected of him. Discrepancy. In the intercultural context, discrepancy often involves cultural paradoxes -situations that exhibit a contradictory nature and violate conceptualizations of expected cultural behavior (Osland & Bird, 2000). The actor’s mindset before the trigger is “We think we know, but we don’t,” as seen in this example. An American was supervising the turnaround of a department in an international development agency in Guatemala. Although her natural leadership style was participative, she observed that her employees were not used to giving input on decisions and were more comfortable with an autocratic leadership style, confirming what she already knew about the culture. Therefore, she redesigned the department herself after interviewing each employee at length about their jobs. They accepted her decisions without complaint for months until she and her boss designed new workstations, prompting a mini-rebellion. She asked employees and cultural mentors questions to determine why this particular decision, out of the hundreds of autocratic decisions she’d made, provoked resistance. The previous decisions fell into the employees’ extensive zone of indifference (Barnard, 1968), whereas the workstations made it more difficult for employees to meet their social needs at work in the accustomed manner. In this particular organizational context, she learned that the importance of social relationships trumped the beliefs that superiors know best and should make decisions. This cultural paradox triggered an occasion for sensemaking, which led, in turn, to a synthesis that gave her a clearer understanding about when she needed to be participative with a hierarchical workforce. Deliberative Initiative. In the intercultural context, deliberate initiatives result from a conscious acknowledgement of incompetence. Before being transferred to India, a Japanese executive 18 had spent his entire international career in Europe. He had no prior knowledge or experience of India, which he and his boss viewed as a serious obstacle. With his boss’s support, he began reading, took a seminar on doing business in India, and sought out cultural mentors to learn as much as possible about the culture. In this case, the transfer to an unfamiliar country was the trigger event that prompted him to initiate intercultural sensemaking (internal request) in conjunction with his boss’s recommendation (external request). Role of Expectation. Expectation plays a role in all three trigger conditions. The violation of expectations is figural in both novelty and discrepant trigger events. In novelty, the surprise is unexpected and refers to something that stands out, is unfamiliar or previously unknown. In discrepancy, the reality differs from the expected, and expectations can be either undermet (e.g., I was not praised for my work as I expected) or overmet (e.g., I thought my work would be praised but not so lavishly). In deliberate initiative, the message is communicated that one does not know what to expect and should therefore pay closer attention and explore expectations. Proposition 5: The greater the level of novelty, the more likely the event will trigger a reaction. Proposition 6: The greater the level of discrepancy, the more likely the event will trigger a reaction. Proposition 7: The presence of internal or external requests for deliberate initiative will trigger a reaction. Trigger Threshold Not all disruptions come to be viewed as trigger events. More than one discrepancy may be necessary to exceed a threshold level (Feldman, 1981), and individual differences in cognitive style (Feldman, 1981) as well as practice and experience (Billings, Milburn & Schallman, 1980) influence threshold levels. The factors that appear to moderate trigger conditions and determine the threshold level for trigger events in intercultural sensemaking are: intensity, salience, persistence, and accumulation. Trigger events can be either instantaneous -- demanding immediate attention and action 19 (Louis & Sutton, 1991) -- or incremental -- receiving full attention only after an exposure period (Billings, Milburn & Schallman, 1980). Intensity. The three trigger conditions identified by Louis and Sutton (1991) -- novel, discrepant, and deliberate – can vary in strength. The more unique an event, the more it diverges from one’s expectations, and the stronger the call to pay conscious attention constitute the intensity that determines whether a disruption is perceived as a trigger event. The degree of intensity is also reflected in the emotional or physiological reaction to the disruption. Proposition 8: The greater the level of intensity, the more likely a condition will rise to the threshold of a trigger. Salience. Disruptions do not occur in a vacuum but against a noisy backdrop of numerous stimuli and other disruptions. Not every disruption stands out sufficiently and shifts, in the terms of Gestalt psychology, from ground to figure. Thus, the salience of a disruption will influence whether it becomes a trigger event. Proposition 9: The greater the level of salience, the more likely a condition will rise to the threshold of a trigger. Persistence. In Cowan’s model of the problem recognition process, persistence is defined as “a single discrepant cue that lasts for an extended period of time” (Cowan, 1986: 769). A cultural cue or event that persists over time is also more likely to be perceived as a trigger event than a one-time occurrence. Proposition 10: The greater the level of persistence, the more likely a condition will rise to the threshold of a trigger. Accumulation. Cowan (1986: 769) notes that the problem recognition process is “the accumulation of discrepancies between what is being observed and what is desired.” Discrepancies build up until they exceed the threshold and prompt individuals to respond. With respect to trigger events and intercultural sensemaking, individuals perceive a set of small events related to the 20 originally perceived disturbance. After the accumulation of a sufficient number, they constitute a trigger event and a round of sensemaking ensues, as shown in the opening vignette. Proposition 11: The greater the level of accumulation, the more likely a condition will rise to the threshold of a trigger. In our opening vignette, the American in Germany noticed the lack of greeting behavior in the beginning of his stay but was too busy adjusting to a new country to pursue it; at that time it was not salient. As time went on, he continued to notice the persistence of the behavior and the accumulation of apparently related discrepancies, all dealing with intimacy and social distance. He strongly disliked being ignored, an emotional reaction that contributed to the intensity of the trigger event. He mentioned instances in other cultures where he failed to understand behaviors but was not motivated enough to decode their significance. The lack of greeting behavior and related cues, however, surpassed the trigger threshold and generated intercultural sensemaking. Event Reactions Disruptions and trigger events can cause cognitive, emotional and sometimes physiological responses that may lead to event reactions. For example, one cognitive response is a conscious or unconscious evaluation of the trigger event that prompts a fight-or-flight reaction (Cannon, 1932). Cognitive reactions may also be driven by emotion, which is closely tied to trigger event perception. An emotional response may be the first signal of a disturbance, for example, when negative feedback causes anxiety that in turn leads to increased vigilance. “The cognitive function of emotions is to direct attention to the relevant aspects of the environment in the service of action tendencies for altering that environment….cognition is generally constrained by the type of emotional state” (Lewis, 2004: 8). When strong emotions accompany the trigger event, another form of sensemaking is likely to occur, the emotional appraisal or interpretation that Lewis (2004) links to neurobiology. He argues that a bidirectional interaction occurs between emotions and cognition because emotions are needed 21 “to cement emerging interpretations … and emotions are maintained by those same interpretations, locking cognition and emotion into an enduring resonance.” In sum, emotions play an important role in the perception of trigger events, the ensuing cognitive and emotional sensemaking, and the way future trigger events are perceived. Physiological responses, such as heart acceleration, nausea, and so forth may result from trigger events (Lewis, 2004). As with emotion, such reactions can be the first signal that a trigger event is significant and warrants attention. On the heels of cognitive, emotional and physiological responses to trigger events, we find three types of event reactions in the intercultural context: fight-or-flight, acceptance, or intercultural sensemaking, described below. Fight-or-Flight. Cannon’s (1932) fight-or-flight response describes the physiological reaction to threats and stress, which originally primed humans for fighting or fleeing danger in order to survive. In the intercultural context, the fight response takes the form of imposing one’s own meaning on the situation and refusing to consider another perspective. The flight response is a withdrawal from the other culture -- isolating oneself from contact, what anthropologists call “enclaving” with members of one’s own culture. Flight may also be accompanied or rationalized by misattributions about the other culture. Cultural differences are often explained using incorrect assumptions and negative evaluative judgments. In other cases, the withdrawal may be accompanied by an emotional hijack in which emotion overwhelms reason (Goleman, 1998). Ranting tourists and expatriates serve as handy examples. Fight-or-flight reactions represent a cognitive response that is restricted to one’s own cultural framework. Acceptance. The acceptance reaction implies a passive approach that neither rejects the trigger event nor attempts to understand it. Instead, cultural novelty, discrepancy or information are 22 simply accepted as “this is the way it is.” When trigger events are perceived as a source of stress, they might provoke an alternative to the fight-or-flight response that is more in keeping with an acceptance reaction. Researchers identified a tend-and-befriend stress response in women that has a different physiological makeup and involves nurturing children and forming social alliances for protection (Taylor, Klein, Lewis, Gruenewald, Gurung & Updegraff, 2000). The acceptance reaction implies adaptation to the expectations of another culture without necessarily understanding them. Some authors assume that possessing attributional knowledge, an understanding of why certain behavior is appropriate in a specific context (Bird, Heinbuch, Dunbar & McNulty, 1993), is positive. For example, Archer (2001) addresses the importance of cultural understanding or sensemaking when describing the reaction to culture bumps (unexpected behavior). “It is assumed that human beings feel disconnected when encountering a cultural difference and adopt coping strategies in an attempt to alleviate their feelings of anomie. Implicit within these strategies is the assumption that if the motive for the behavior were known, then the discomfort would be alleviated” (Archer, 2001: 7). Storti’s (1990) model of cultural adaptation also assumes that seeking to understand the other culture is a better response than flight. His model also demonstrates the interplay of cognitive and emotional responses to a cultural incident. The model begins by stating that people expect others to behave like they do, but they do not. Thus, when a cultural incident occurs, it provokes a strong reaction, such as fear or anger, prompting a choice point. People either withdraw from the other culture, a negative coping reaction, or they make an effort to put aside their emotional reaction and think about the incident cognitively—“What’s going on here?” In doing so, they become aware of their emotional reaction and look for its cause, which in turn makes the reaction subside. This allows them to observe and decode the situation and develop culturally appropriate expectations. As a result, the trigger event -- the cultural incident -- is no longer novel or attached to discrepant expectations. 23 The underlying assumption of this model is that successful adaptation means acknowledging that one’s own cultural scripts do not explain behavior in another culture. Once emotion has been dealt with, Storti’s cultural adapters engage in a form of sensemaking when they observe the situation and develop accurate expectations. Like Archer and Storti, the authors assume that seeking cultural understanding is a positive response to trigger events. The next section describes how this is done in intercultural sensemaking. Intercultural Sensemaking Osland and Bird (2000; see also Bird & Osland, 2006 for a more detailed description) developed a model of intercultural sensemaking, which is based on the premise that culture is both paradoxical (Fang, 2006) and contextual. Intercultural sensemaking is an ongoing process involving an iterative cycle of sequential events: framing the situation, making attributions, and selecting scripts, which are undergirded by constellations of cultural values and cultural history. The process begins in Framing the Situation when an individual identifies a context and then engages in indexing behavior, which involves noticing or attending to stimuli that provide cues about the situation. The next phase is Making Attributions, a matching process in which cues are linked to evaluation. Inferences are drawn about the people involved, such as their intent, reliability and so forth. The third step, Selecting a Script, involves choosing an appropriate schema or cultural scripts (Triandis, Bontempo, Villareal, Asai & Lucca, 1984: 1346). The process of sensemaking is subject to the Influence of Cultural Values, e.g., individualism versus collectivism, high versus low power distance (Osland & Bird, 2000).. The Influence of Cultural History, the shadow of tradition and inherited mindsets (Fisher, 1997) must also be taken into consideration. Returning to the American in Germany in our opening vignette, the discrepant trigger event was the absence of smiles and greeting behavior and the American’s awareness of his emotional 24 response of discomfort. In his own culture, failure to acknowledge a greeting would be framed as rudeness, which he speculated was not the correct explanation. He made a conscious decision to learn about greeting behavior among strangers in the street (framing the situation). He tested a hypothesis from his experience in another culture (avoiding incurring obligations), which is a sensemaking strategy; but it did not match what he was seeing. As he paid closer attention to interactions and quizzed a cultural mentor, he saw that greeting behaviors and, by extension, intimacy varied depending on the contexts and the people involved (making attributions). He formed a second hypothesis that greeting behavior was part of a larger cultural pattern of social distance (influence of cultural values), which he tested with his subordinates. Satisfied with this explanation, he adapted his expectations and behavior (selecting a script). Outcomes Learning and knowledge acquisition are frequently the outcome of intercultural sensemaking, which translates into increased cultural understanding and perhaps effectiveness. There are, however, other outcomes, proposed below: development of cognitive schema, automaticity, cue identification and pattern recognition, increased attention/mindfulness to trigger events, emotional earmarks, and ascending restabilization. Sensemaking is a form of social learning that leaves a cognitive trail. Cues and actions form schemas that will guide future behavior and influence the cues and patterns that are subsequently identified and recognized. When similar events are observed, an automatic response is more likely. Learned lessons from a prior round of sensemaking will determine the level of arousal, attention and perception devoted to similar situations in the future. Such lessons also create expectancies that shape what will be monitored in the future. 25 Another outcome is that uncertain situations in general may be more likely to trigger greater attention and mindfulness. The lesson from acknowledging “incompetence” or a lack of understanding is that other uncertain situations warrant attention and perhaps require intercultural sensemaking. The resulting sustained vigilance is a form of deliberate initiative directed at the attention stage of the process. Along with a cognitive trail, intercultural sensemaking is likely to produce emotional earmarks. As noted previously, many trigger events involve emotions that generate an emotional appraisal that accompanies sensemaking. These emotional connections and learned schemas are also filed in the brain. Awareness of and sensitivity to similar emotions in the future could trigger attention leading to intercultural sensemaking. In addition, there is another emotional component to successful sensemaking. The sense of mastery and achievement that people experience when they “crack the code” of another culture can engender a feeling of pride (Osland,1995) that is reinforcing and makes future sensemaking efforts more likely. The final outcome relates to the definition of trigger events as disturbances in a phase transition characterized by temporary disorder. Intercultural sensemaking can be viewed as a return to order, but at a higher level of cultural understanding, which we refer to as ascending restabilization. Once people reach a plateau of cultural understanding that allows them to function at an acceptable level, trigger events seem to be the primary stimulus for acquiring a higher level of intercultural competence in a specific culture. DISCUSSION The major contributions of this paper are the explicated definitions of trigger events in various research and practitioner disciplines and a proposed process model of trigger events in intercultural sensemaking. The model begins with personal characteristics – intercultural expertise, stance, 26 curiosity, and emotional resilience – that moderate the arousal and attention paid to trigger conditions. The typology of trigger conditions identified by Louis and Sutton (1991) – novelty, discrepancy, and deliberate initiative – seems to be a thorough list with respect to the intercultural context. We considered whether there might be additional categories, such as change or compelling problems in the information stream (Thomas, Clarke, & Gioia, 1993; Weick, Sutcliffe, & Obstfeld, 2005); but cultural change could be categorized as either novelty or discrepancy and compelling cultural problems could result from any of Louis and Sutton’s trigger conditions. Therefore, we did not expand the list of trigger conditions. Trigger conditions rise to the threshold of trigger events, moderated by the threshold characteristics of intensity, salience, persistence and accumulation. At this junction, there is a choice point among three event reactions: fight or flight, acceptance, or intercultural sensemaking. The last choice consists of framing, attributing, and selecting the appropriate script by relying on a variety of sensemaking strategies. Various outcomes of intercultural sensemaking are proposed, most of which have implications for future sensemaking. The model portrays attention, arousal, and the trigger threshold as precursors to intercultural sensemaking in a unidirectional, iterative process, like a spiral moving upwards. The reality, however, is doubtless less neatly linear and more iterative, doubling backwards and forward. One could argue, for example, that intercultural sensemaking actually begins with the trigger event by setting the frame that accounts for the disturbance. In their data/frame model of sensemaking, Klein and his colleagues contend that: “data are used to construct a frame (a story or script or schema) that accounts for the data and guides the search for additional data. At the same time, the frame a person is using to understand events will determine what counts as data. Both 27 activities occur in parallel, the data generating the frame, and the frame defining what counts as data” (Klein et al., 2005: 20). Thus, as soon as arousal and attention occur, individuals may begin questioning their assumptions and start seeking additional cues related to the trigger event. All aspects of the model, which is based on the literatures on trigger events, sensemaking and intercultural competence, and on pilot interviews with intercultural experts, should be tested empirically. The model has the following theoretical implications. It treats culture learning as an organic emergent process, grounded in personal experience. paradoxical nature of culture. It acknowledges the inherently It emphasizes meta-cognition skills required for intercultural competence and cultural intelligence that are helpful to people who work in a variety of cultures (Thomas & Inkson, 2004). Unlike some intercultural and sensemaking models, this holistic approach recognizes the importance of both cognition and emotion. Future research could develop measures for the basic triggering conditions of novelty, discrepancy, and deliberative initiation. As Griffith noted, “Louis and Sutton (1991) do not empirically test their theory of triggers, although they do present concepts that could be used to develop measures” (1999: 485). Perhaps one of the reasons trigger events have not been studied, is that, like research on problem detection, laboratory studies present subjects with given situations or problems. These situations or problems may function like deliberate triggers with some subjects, but they do not necessarily constitute a disruption in the subjects’ cognitive flow. Therefore, trigger events are best studied in naturalistic settings. More research is needed to understand why some people pay attention to triggers and others do not and to discover which triggers are most commonly perceived and by whom. There may be other situational contingencies that lead to the perception of 28 trigger events. Furthermore, future research might be able to relate certain types of trigger events with specific sensemaking strategies, which would be helpful for training purposes. Another line of research on trigger events in intercultural sensemaking would focus on experts in intercultural competence. This is attractive for several reasons. First, unlike novices, they have already reached a plateau of cultural understanding and have apparently moved beyond that plateau by experiencing and working through significant trigger events. Second, they are more likely than novices to avoid the fight or flight response and opt for sensemaking. Finally, they have presumably developed more expertise in intercultural sensemaking and could explicate the reasoning and strategies they employ. This expertise would be very useful in developing training materials and programs. The impact of national differences in cognition on the perception of trigger events and intercultural sensemaking represents another area of research that may hold promise. Choi & Nisbett (2000) have addressed the influence of cultural variation related to surprise and contradiction. According to Nisbett’s (2003) analytic-holistic framework, people from Western nations tend to be analytical, focusing on separate elements that can be understood independent of one another and dispositions (internal attribution). By contrast, people from East Asia tend to use holistic thinking that focuses on relationships. Thus, Choi, Koo, and Choi (under review) contend that national differences influence sensemaking along four dimensions: attention, causal attribution, tolerance for contradiction, and perception of change. Lin and Klein (in process) argue further that national differences in cognition influence the perception of anomalies and the subsequent search and use of information in the sensemaking process. One of the benefits of studying the intercultural context is that it serves as an extreme example that provides lessons for more subtle issues in a domestic context. Trigger events and the need for intercultural sensemaking are an inherent part of the struggle to comprehend cultural difference. 29 Living within one’s own culture, people are called upon less frequently to question or modify their assumptions because their social networks may consist of people similar to them or of people who do not threaten them. Oftentimes the very minorities who could cause them to reevaluate their perspectives are forced to tone down or silence discrepant views. Thus, members of the dominant culture are more likely to operate on automatic pilot and unconscious thought and may face diversityrelated trigger events only sporadically. When they do, however, it seems likely that the proposed model could also describe and perhaps guide their sensemaking efforts. Research could tell us whether the same phenomenon occurs in the context of domestic diversity. People can be trained to scan for and pay close attention to trigger events. Experiential training sessions often design in trigger events as teachable moments. These could be used more consciously and followed up with structured debriefings that lead participants through the model so they learn to decode situations and use intercultural sensemaking on their own. Participants can be asked to analyze personal trigger events using the model. Finally, training can be designed to teach participants sensemaking strategies that are useful for specific types of trigger events and provide them with opportunities to practice sensemaking. Trigger events play a significant role in moving people who work across cultures from unconscious to conscious incompetence; intercultural sensemaking is a means of helping them advance into the realm of competence and effectiveness. 30 REFERENCES Adler, N. J., & Gundersen, A. 2008. International Dimensions of organizational Behavior. Cincinnati, OH: Thomson South-Western. Apfelthaler, G. and Karmasin, M. 1998. Do you manage globally or does culture matter at all? Paper submitted to the Academy of Management Annual Meeting, San Diego. Archer, C.M. l986. Culture bump and beyond. In J. M. Valdes (Ed.), Culture bound: Bridging the cultural gap in language teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press: 170-178. Archer, C. M. 2001. Training for effective cross cultural communication. (April 20). Accessed 1/12/07. http://www.culturebump.com/docs/whitepaper.doc, Barnard, C.I. 1968. The functions of an executive. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Bennett, M. J. 1993. Towards ethnorelativism: A developmental model of intercultural sensitivity. In M. Paige (Ed.), Education for the intercultural experience. Yarmouth, ME: Intercultural Press. Berger, C. & Calabrese, R. 1975. Some explorations in initial interactions and beyond: Toward a developmental theory of interpersonal communication. Human Communication Research, 1: 99-112. Berger, C. R., & Douglas, W. 1981. Studies in interpersonal epistemology III: Anticipated interaction, self-monitoring and observational context selection. Communication Monographs, 48: 183– 196. Berscheid, E., Gangestad, S. W., & Kulakowski, D. 1984. Emotion in close relationships: Implications for relationship counseling. In S. D. Brown & R. W. Lent (Eds.), Handbook of counseling psychology. 435-476. New York: Wiley. Billings, R.S., Milburn, T.W. & Schaalman, M.L. 1980. A model of crisis perception: A theoretical and empirical analysis. Administrative Science Quarterly, 25(2): 300-316. Bird, A., Heinbuch, S., Dunbar, R. & McNulty, M. 1993. A conceptual model of the effects of area studies training programs and a preliminary investigation of the model’s hypothesized relationships. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 17(4): 415-436. Bird, A. & Osland, J.S. 2006. Making sense of intercultural collaboration. International Journal of Management and Organizations, 3(4): 115-132. Black, J. S., Morrison, A., & Gregersen, H. 1999. Global explorers: The next generation of leaders. New York: Routledge. 31 Black, J. S., & Gergersen, H. B. 1991. The other half of the picture: Antecedents of spouse crosscultural adjustment. Journal of International Business Studies, 22: 461-477. Blakeslee, S. 2006. Cells That Read Minds. New York Times January 10. Bower, G. H. 1992. How might emotions affect learning? In S.Å. Christianson (Ed.), The handbook of emotion and memory: Research and theory: 3-31. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Bradley, M. M., & Lang, P. J. (2000). Measuring emotion: Behavior, feeling, and physiology. In R. D. Lane & L. Nadel (Eds.), Cognitive neuroscience of emotion. 242-276. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Brannen, M.Y., Gomez, C., Peterson, M.F., Romani, L., Sagiv, L. & Wu, P.C. 2004. People in global organizations: Culture, personality, and social dynamics. In H.W., Lane, M.L. Maznevski, M.E. Mendenhall & J. McNett (Eds.), The Blackwell handbook of global management: A guide to managing complexity: 26-54. London: Blackwell. Cannon, W. B. 1932. The Wisdom of the Body. New York: Norton. Choi, I. & Nisbett, R.E. 2000. Cultural psychology of surprise: Holistic theories and recognition of contradiction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79: 890-905. Choi, I, Koo, M., & Choi, J. (under review). Measurement of Analytic-Holistic Thinking Styles. Unpublished Manuscript. Cohen, A. P. 1985. The symbolic construction of community. London: Routledge. Cowan, D. 1986. Developing a process model of problem recognition. Academy of Management Review, 11(4): 763-776. Cranton, P. 1994. Understanding and promoting transformative learning: A guide for educators of adults. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Christoffersen, K, Woods, D.D., Blike, G.T. 2001. Extracting event patterns from telemetry data. In: Proceedings of the human factors and ergonomics society 45th annual meeting, Minneapolis/ St. Paul, 8–12 October 2001. HFES, Santa Monica: 409–413. Chow, R., Christoffersen, K., Woods D. D. 2000. A model of communication in support of distributed anomaly response and replanning. In: Proceedings of the XIVth Triennial Congress of the International Ergonomics Association and 44th annual meeting of the human factors and ergonomics society, 1: 34–37 Deardorff, D.K. 2006. Identification and assessment of intercultural competence as a student outcome of internationalization. Journal of Studies in international Education, 10(3): 241-266. 32 Deardorff, D. K. 2004. The identification and assessment of intercultural competence as a student outcome of international education at institutions of higher education in the United States. Unpublished dissertation. North Carolina State University, Raleigh. Derryberry, D., & Tucker, D. M. 1994. Motivating the focus of attention. In P. M. Niedenthal & S. Kitayama (Eds.), The heart's eye: Emotional influences in perception and attention: 167-196. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. Fang, T. 2006. From “onion” to “ocean”: Paradox and change in national cultures. International Studies in Management & Organization, 35(4): 71-90. Feldman, 1981. XXXX Fisher, G. 1997. Mindsets: The role of culture and perception in international relations. Yarmouth, ME: Intercultural Press. Garey, J., Goodwillie, A., Frohlich, J., Morgan, M., Gustafsson, J., Smithies, O., Korach, K. S., Ogawa, S., & Pfaff, D. W. Genetic contributions to generalized arousal of brain and behavior. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 100(19): 11019-11022. Gazzaniga, M. S. 2004. The Cognitive Neurosciences, 3rd Edition. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Goleman, D. 1998. Working with Emotional Intelligence. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. Gollwitzer, P. M. 1996. The volitional benefits of planning. In P. M. Gollwitzer & J. A. Bargh (Eds.), The psychology of action: Linking cognition and motivation to behavior: 287-312. London: Guilford Press. Griffith, T. 1999. Technology features as triggers for sensemaking. Academy of Management Review, 24(3): 472-488. Gudykunst, W.B. 1994. Bridging differences: Effective intergroup communication. (2nd. Ed.) London: Sage. Gudykunst, W. B. and Kim, Y. Y. 1997. Communicating with strangers: An approach to intercultural communication. Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill. Howell, W. S. 1982. The empathic communicator. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth. Humair, J. & Ward, J. 1998. Smoking-cessation strategies observed in videotaped general practice consultations. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(1): 1-8 Joosten, S. 1994. Trigger modelling for workflow analysis. In R. Oldenbourg (Ed.), Proceedings of the 1994 Conference on Workflow Management: 236-247. Vienna: Munchen. 33 Kealey, D. J. 1996. The challenge of international personnel selection. In D. Landis and R. S. Bhagat (Eds.) Handbook of Intercultural Training, 2nd edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage: 81-105. Kashdan, T. B. & Silvia, P. J.. 2008. Curiosity and interest: The benefits of thriving on novelty and change. In S. J. Lopez, (Ed. ) Handbook of Positive Psychology, 2nd edition. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press: In press. King, K.P. 2004. Furthering the theoretical discussion of the journey of transformation: Foundations and dimensions of transformational learning in educational technology. New Horizons in Adult Education, 18(4): 4-50. Klein, G. 1998. Sources of power: How people make decisions. Boston: MIT Press. Klein, G., Pliske, R. Crandall, B. & Woods, D. 2005. Problem detection. Cognition, Technology and Work, 7: 14-28. Klein, G., Phillips, J.K., Rall, E.L., & Peluso, D.A. (forthcoming). A data/frame theory of sensemaking. In. R.R. Hoffman (Ed.), Expertise Out of Context (NJ: Erlbaum, Mahwah). Kluckhohn, F. & Strodtbeck, F. 1961. Variations in values orientations. Evanston, IL: Row, Peterson. Langer, E. J. 1997. The power of mindful learning. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. Levy, O., Beechler, S., Taylor, S., & Boyacigiller, N. 2007. “What do we talk about when we talk about global mindset: Managerial cognition in multinational corporations, Journal of International Business Studies. (In press). Lewis, M.D. 2005. Bridging emotion theory and neurobiology through dynamic systems modeling. Behavioral and Brain Science, 28: 169-194. Lin, M., & Klein, H.. (In process) Culture and sensemaking: An examination of macrocognition. Working Paper. Louis, M. R 1980. Surprise and sensemaking: What newcomers experience in entering unfamiliar organizational settings. Administrative Science Quarterly, 25: 226-251. Louis, M. R. & Sutton, R. I. 1991. Switching cognitive gears: From habits of mind to active thinking. Human Relations, 44: 55-76. Luthar, S. S. & Cicchetti, D. 2000. The construct of resilience: Implications for interventions and social policies. Development and Psychopathology, 12: 857-885. McKay, K. N., Buzacott, J. A., Charness, N. & Safayeni, F. R. 1992. The scheduler’s predictive expertise: An interdiciplinary perspective. In G. I. Doukidis and R. J. Paul (eds), Artificial intelligence in operational research. 139-150. Basingstoke: Macmillan. 34 Mezirow, J. 1991. Transformative dimensions of adult learning. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Mezirow, J. 1997. Transformative learning: Theory to practice. In P. Cranton (Ed.), Transformative learning in action: Insights to practice (New Directions in Adult and Continuing Education, No. 74): 5-12. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Mezirow, J. 2000. Transformative learning as a meaning becoming clarified. In. C. Wiessner, S. R. Meyer & D. A. Fuller (Eds.), Challenges of practice: Transformative learning in action, proceedings of the third international transformative learning conference. New York: Teacher’s College Columbia University: 3344-346. Nisbett, R.E. (2003). The geography of thought: How Asians and Westerners think differently…and why. New York: The Free Press. Oatley, K., & Johnson-Laird, P. N. 1987. Towards a cognitive theory of emotions. Cognition and Emotion, 1: 29-50. Ong, A. D., Bergeman, C. S., Bisconti, T. L., & Wallace, K. A. 2006. Psychological resilience, positive emotions, and successful adaptation to stress in later life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91(4): 730-749. Osland, J. S. 1995. The adventure of working abroad: Hero tales from the global frontier. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Osland, J.S. and Bird, A. 2000. Beyond sophisticated stereotyping: cultural sensemaking in context. Academy of Management Executive, 14(1): 65-76. Osland, J.S., & Bird, A. 2006. Global leaders as experts. In W. Mobley & E. Weldon (Eds.), Advances in Global Leadership, 4: 125-145. London: Elsevier. Osland, J.S., Bird, A.,.Osland, A. and Oddou, G (2007). Expert Cognition in High Technology Global th Leaders.” Proceedings of the Proceedings, 8 Naturalistic Decision Making Conference, Monterey. Paige, M. 1993. (Ed.). Education for the intercultural experience. Yarmouth, ME: Intercultural Press. Parker, J. & Randall, P. 1996. Using behavioural theories in social work. London: Open Learning Foundation. Posner, M. & Rothbart, M. 1998. Attention, self-regulation and consciousness. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, 353: 1915-1957. Senglaub, M. 2001. Course of action analysis within an effects-based operational context. Albuquerque, NM: Sandia National Laboratories. 35 Sims, H.P., Jr., & Gioia, D.A. 1986. The thinking organization: Dynamics of organizational social cognition. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Speilberger, C., & Starr, L. Curiosity and exploratory behavior. In XXXX. Starbuck, W.H. & Milliken, F.J. 1988. Executives’ personal filters: What they notice and how they make sense. In D. Hambrick (Ed.), The executive effect: Concepts and methods for studying top managers. Greenwich, CT: JAI. Sternberg, R. & Davidson, J. (Eds.) 1994. The nature of insight. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Storti, C. 1990. The art of crossing culture, Yarmouth, ME: Intercultural Press. Taylor, S.E., Klein, L. C., Lewis, B. P., Gruenewald, T. L., Gurung, R. A., & Updegraff, J. A. 2000. Biobehavioral responses to stress in females: Tend-and-befriend, not fight-or-flight. Psychological Review, 107(3): 411-429. Thayer, J. F., & Lane, R. D. 2000. A model of neurovisceral integration in emotion regulation and dysregulation. Journal of Affective Disorders, 61: 201-216. Thich, N, H. 1991. Peace is every step: The path of mindfulness in everyday life. New York Bantam Books. Ting-Toomey, S. 1999. Communicating across cultures. New York: Guilford Thomas, D. & Inkson, K. 2004. Cultural intelligence: People skills for global business. New York: Berrett-Kohler. Thomas, J.B., Clark, S.M. and Gioia, D. 1993. Strategic sense making and organizational performance: linkages among scanning, interpretation, acquisition and outcomes. Academy of Management Journal, 36: 239-270. Triandis, H. C., Bontempo, R., Villareal, M. J., Asai, M., & Lucca, N. 1984. Individualism and collectivism: Cross-cultural perspectives on self-ingroup relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(2): 323-338. Walsh, J.P. & Ungson, G.R. (1991). Organizational memory. Academy of Management Review, 16: 57-91. Weick, K.E. 1979. The Social Psychology of Organising. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. Weick, K. E. 1995. Sensemaking in organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Weick, K. E., Sutcliffe, K. M., & Obstfeld, D. 1999. Organizing for high reliability: Processes of collective mindfulness. Research in Organizational Behavior, 21: 13-81. 36 Wells, A., & Matthews, G. 1994. Attention and emotion: A clinical perspective. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. 37 Trigger Event 2/16/2016 39