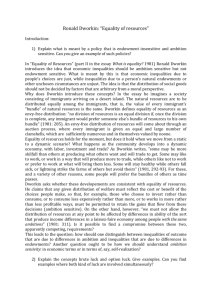

On Dworkin`s Brute Luck-Option Luck Distinction

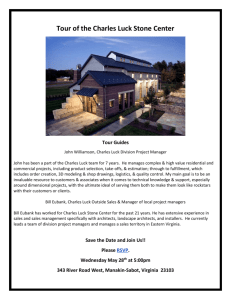

advertisement