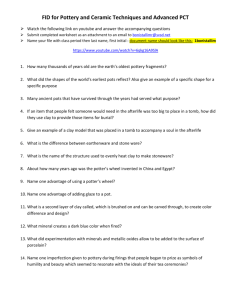

North Carolina indigenous pottery

advertisement

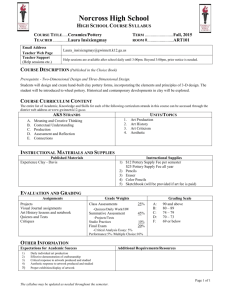

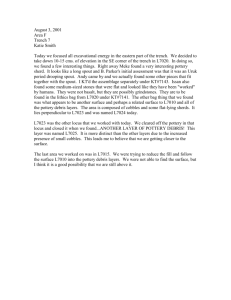

North Carolina indigenous pottery a Summary View Archaeology Lab ANTL 207 Background Pottery is common in North Carolina archaeological sites dating after 1000 BC. Its rather abrupt appearance about then signals the start of the Woodland Period, the era when people began living in semi-permanent villages and cultivating gardens of seed plants to supplement food obtained by hunting and gathering. During the Woodland, which lasted until AD 1000, people used pottery for storing food and water, and for cooking. Today, archaeologists can learn a great deal about the life of North Carolina's Woodland people by studying the pottery they left behind. For instance, archaeologists use pottery styles as a tool to study relationships among the different groups of Indian people living in North Carolina then. Archaeologists also study how pottery styles changed to learn about such things as diet and cooking techniques of earlier peoples. To archaeologists, pottery is an important artifact because it can often indicate how old a site is. When fired, clay is very durable and is preserved long after organic materials decay. Because of its durability, pottery pieces (sherds), along with stone tools, make up much of what archaeologists recover from Woodland period sites. Because Woodland groups changed pottery styles and production techniques over time, pottery is a useful chronological marker. Also, because pottery styles are distinctive to particular groups of people, they can serve as cultural markers. Native cultures living in the three regions of North Carolina--the Coastal Plain, the Piedmont, and the Mountains--during 2 the Woodland were not the same. Their pottery styles and pottery making traditions varied. Pottery is made from clay that is dug from the ground. Clay that was good for making pottery can be found in almost every part of North Carolina. To make pottery, Native Americans first had to dig the clay and then pound it to make sure there were not any big lumps in it. They mixed the clay with water to make it a putty with play-dough like consistency so they could shape it into bowls and other pottery vessels. To make a piece of pottery, the potter would first shape the bottom of the vessel from long coils or ropes of clay, and then add other coils to build the sides of the pot. After the pottery vessel was shaped, the potter would smooth the inside and outside surfaces with his or her fingers, or a piece of shell or stone. Smoothing the pottery helped hold the coils together. Usually, the potter would then add patterns or designs to the outside of the pot. Archaeologists call this surface treatment. The pot was set out to dry. The next step was placing it in a fire. Burnable materials, such as bark or wood, were placed around the pot, which was left in the hot fire until the clay became hard. Most vessels North Carolina Indians crafted were used for cooking. Typically, foods were boiled by placing the pot directly over a fire. Thus, cooking pots were usually deep bowls or jars. The latter had pointed bases which could be placed upright in deep ash. Shallower bowls were also sometimes made; these were used for serving food. The specific shapes changed from one period to another. Hence, archaeologists can use vessel shapes to help date the pottery they find. Surface treatment is also an important element used by archaeologists for dating pottery. In the coastal areas of North Carolina, early Woodland people sometimes wrapped a paddle with cord and pressed the paddle against the unfired clay pot. Pots decorated in this way are called cord-marked. Fishing nets were also pressed against the surface of pots to create a criss-crossed pattern. In later times, people cut or incised lines into the pottery, or stamped it with carved wooden paddles. Sometimes dried corncobs and fabric were used to impress designs on pottery. Late Woodland coastal peoples often polished the outside of the pot with a smooth stone, and this is called a burnished finish. Pottery from other parts of the state has different types of decoration. In addition to variation in shape and surface treatment, pottery vessels often differ in temper. Temper is material that was mixed with clay to make the finished pottery stronger and less likely to crack during firing. Sand, crushed shell, bits of fired clay, and small pebbles have all been used as tempering materials in North Carolina pottery. Archaeologists have found that looking at temper type is another good way to date pottery. 3 The North Carolina Coastal Plain Archaeologists spend lifetimes studying the array and sequencing of pottery styles for the regions in which they specialize. Those studying the Coastal Plain's history are no exception. They've identified pottery types and ordered them on timelines; they've studied how decorative and manufacturing styles fan geographically and where their points of origin might be. These studies have led to a theory: early Woodland people living on the Coastal Plain sat at a cultural frontier where traditions from the north and the south met. The effect of these influences divided North Carolina's Coastal Plain in half during the Woodland, about at the Neuse River line. North of the Neuse, people decorated pottery with cord impressions and tempered clay with sand, both of these traits having been derived from a Middle Atlantic tradition that filtered down through southeastern Virginia. The earliest pottery of this kind in North Carolina dates to about 1000 BC. It turns up at a site called Parker, which sits along the Deep Creek tributary of the Tar River. Later, people in the state's northern Coastal Plain picked up other decorative ideas. Pottery surfaces decorated with fabric impressions and net impressions gained popularity by 800 BC. About that time, a decoration stamped with a carved (not cord-wrapped) paddle also got a foothold. Called simple stamping, this technique rendered bold, parallel lines across vessel surfaces. Plain ware with incised decorations found a niche then, too. Throughout the north Coastal Plain, temper across the styles ranged from sand to grit to shell. Meanwhile, North Carolina's southern Coastal-Plain groups picked up notions of their own. Beginning in the late Archaic as early as 2000 BC, people adopted a practice introduced from the South Carolina and Georgia coasts of making a smooth, thick clay vessel, which archaeologists call Stallings ware. The temper they used was natural plant fiber, like moss or grass. Resembling wide-mouthed flower pots, the vessels were made by people who lived mostly south of the Neuse River. Similar to what happened in the northern Coastal region, other pottery styles eventually filtered into southern Coastal life. By 1300 BC, people decorated some vessels with dots or lines, which were inscribed with a stick before the pot was fired. Later, after 500 BC, simple stamping with bold lines and checked designs became popular. Among the southern Coastal styles, temper switched from the fiber in Stallings pottery to sand, grit, and sometimes shell. Horizontally divided north-south in terms of pottery preferences, the Coast is also split vertically into two geological mini-regions. The Tidewater is the eastern half, indented with estuaries and sounds; and the Interior Coastal Plain is the western portion between the Tidewater and the Piedmont. Early in the Woodland period, it seems people lived mostly on the Interior Coastal Plain along the same small streams that their Archaic predecessors preferred. Their 4 encampments were small, stable bases like those most contemporary Piedmont and Mountain groups had. Similarly, their main source of meat was the white-tailed deer along with other smaller animals, birds, and turtles. Yet, unlike their inland neighbors, Coastal people developed a greater reliance on shellfish, fish, and other estuarine foods. Groups began a slow drift toward the Tidewater during the early Woodland. By 500 BC, some were making seasonal camps along the rivers, estuaries, and sounds flanking the ocean. In places like Colington and Roanoke Islands, archaeologists think several extended families spent springs and summers gathering shellfish. They left large piles of shells with other refuse, such as animal bone, bits of broken clay pots, and sometimes even human bone, mixed in. In the fall and winter, they left the blustery coastal camps and retreated to the Tidewater's more protected side to occupy villages accessible to riversides, game, and good soils. Archaeologists think most early Woodland groups on the Coastal Plain switched camps at least twice a year. People on the Tidewater seemed to divide the year equally between camps, while those based farther inland stayed put much of the year in their riverside camps to take advantage of immediate stocks of freshwater mollusks and fish. But they, too, left evidence of hunting and butchering tools scattered at sites throughout the Coastal Plain, which suggests they left their main village for regular hunting forays. Regardless of the variability in length of stay, archaeologists think people living in both the Tidewater and Interior Coastal Plain 2,000 years ago were occupying key places long enough to have, in effect, semi-permanent villages. All this links indirectly to pottery making and how it may have edged its way into life. Many archaeologists tend to think pottery-making goes hand in hand with settled village life. Fragile and relatively heavy clay pots tend to be impractical for people who move their settlements frequently. If contemporary hunting and gathering people are any guide, highly nomadic bands don't carry around such heavy, breakable items. So pottery making suggests they stayed settled long enough in places to warrant the work. At minimum, they counted on regular returns to main settlements so they could leave such items there, awaiting them. As archaeologist Bruce Smith puts it, pottery making may have been part of a container revolution that included, too, the widespread use of gourds growing in people's gardens. Clay pots and gourds held water and foods, both wild ones like nuts and cultivated ones like seeds. Pots allowed greater ease and efficiency in cooking and processing foods. They replaced the water-filled skin or bark sacks earlier people put fire-heated rocks in to boil liquid for cooking. In short, Smith thinks a greater demand for waterproof containers may have kept pace with the seed collection systems people were developing. By AD 800, coastal people had abandoned most settlements along tributary streams and relocated along major trunk streams and estuaries. So far, it's unclear how big their villages were, how they were laid out, how the houses were shaped, or how many people each contained. Now that archaeologists are fairly comfortable with the pottery sequences they've developed, they are turning to research to fill in these blanks. A key problem, 5 however, is modern development has rolled over much of the Coast, destroying sites already threatened by erosion. Even so, the artifacts archaeologists find at Coastal sites fill in some images of village life. Large, triangular arrow points they call Roanoke; stone blades of various sizes; stone net sinkers; sandstone abraders; shell pendants; polished-stone ornaments; polished-stone woodworking tools; mats woven from Juncus grass. Like everybody else in North Carolina, Coastal people shifted hunting technology to bows. They worked wood, using the sharp edges of tear-drop shaped celts. They were artists, designing and smoothing jewelry. They had a weaving industry. They made cordage, knotting some, at least, into fishing nets weighted with sinkers. During this period, people were usually buried in graves. Mourners seldom placed objects in the graves. But when they did, they tended to put items like small arrow points. Cremation was another custom practiced in some places at this time. A distinctive practice associated with cremation presumably channeled up from the South. Along North Carolina's southern coast, a culture archaeologists call Cape Fear used low, sand burial mounds. Dated to about AD 950, the round mounds are mostly south of the Neuse River. Most (but not all) contained cremated remains accompanied by grave offerings like pipes, polished stone gorgets, and conch-shell cups. From: rla.unc.edu/lessons/Lesson/L303/L303.htm Partially reconstructed Swannanoa pot 6 Ceramic vessel with carbonized residues 7