JCR 01-0226-34 - Duke University`s Fuqua School of Business

1

Does Elaboration Increase or Decrease the Effectiveness of Negatively versus Positively Framed

Messages?

BABA SHIV

JULIE EDELL BRITTON

JOHN W. PAYNE*

2

*Baba Shiv is associate professor at the Tippie College of Business, University of Iowa, Iowa City,

Iowa 52242-1000 (baba-shiv@uiowa.edu). Julie Edell Britton is associate professor

(jae6@mail.duke.edu), and John W. Payne is the Joseph P. Ruvane, Jr. Professor

(jpayne@mail.duke.edu) at the Fuqua School of Business, Duke University, Box 90120, Durham, NC

27708-0120. Correspondence: Baba Shiv. The authors thank Rohini Ahluwalia, Alexander Fedorikhin,

Shelly Jain, Irwin Levin, Joan Meyers-Levy, Jaideep Sengupta, Paul Windschitl, the editor, associate editor and the three reviewers for their invaluable feedback and guidance at various stages of this project. The authors also thank Alexander Fedorikhin, Angelo Licursi, Justin Petersen, and Himanshu

Mishra for their help in administering the experiments and coding the thought protocols.

3

A robust finding in research on message framing is that negatively framed messages are more (less) effective than positively framed ones when the level of cognitive elaboration is high (low). However, recent research presents evidence that is contrary to previous findings: negative framing being less

(more) effective than positive framing when the level of elaboration is high (low). In this article, we attempt to resolve the conflicting findings by highlighting the moderating roles of motivation and opportunity-related variables on the effectiveness of negative versus positive message frames. Results from two experiments suggest that under conditions of low processing-motivation, negative framing is more (less) effective than positive framing when the level of processing-opportunity is low (high).

Under conditions of high processing motivation, negative framing is more effective than positive framing, irrespective of the level of processing-opportunity.

4

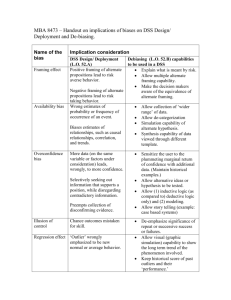

A considerable body of evidence has been amassed in recent years on the relative effectiveness of negatively and positively framed persuasive messages (for reviews see, Levin, Schneider, and

Gaeth 1998; Rothman and Salovey 1997). One robust finding that emerges from this literature is that the relative effectiveness of negative versus positive message framing depends upon the extent of cognitive elaboration the target engages in. As indicated in table 1, negative framing has generally been found to be more effective than positive framing when the level of elaboration is high; when the level of elaboration is low, positive framing tends to be more effective than negative framing. In sharp contrast, the findings reported in Shiv, Edell, and Payne (1997) suggest that negative framing is less effective than positive framing when the level of cognitive elaboration is high; when the level of elaboration is low, negative framing is more effective than positive framing. The broad purpose of this article is to resolve this seeming conflict.

_____________________________________

Insert table 1 about here

_____________________________________

Table 1 highlights several noteworthy differences between Shiv et al. (1997) and previous research, which could potentially account for the conflicting findings: differences in (1) the elaboration manipulation, (2) the dependent measures, and (3) the framing manipulation. In this research, we show that the outcome of message framing depends on whether elaboration is manipulated through opportunity-related factors or through motivation-related factors. Specifically, we show that the results in Shiv et al. 1997 occur when motivation is low and elaboration is manipulated using opportunity-related factors; the results in previous research occur when processingopportunity is not constrained and elaboration is manipulated using motivation-related factors.

Further, our findings suggest that the discrepant findings are neither due to differences in how the framing factor was manipulated nor due to differences in the dependent measures that were used.

5

CONCEPTUAL FOUNDATION

Moderating Roles of Processing Motivation and Opportunity in Message Framing

Previous research on message framing suggests that the effectiveness of negative versus positive framing depends on whether persuasion is determined by the message claims or by heuristics related to non-message factors. One set of heuristics that has been found to influence persuasion relates to the valence of the message frame (e.g., Block and Keller 1995; Maheswaran and Meyers-

Levy 1990; Rothman et al. 1993). These heuristics tend to favor positive framing over negative framing, and, thus, when persuasion is determined by heuristics rather than by message claims, negative framing has been found to be less effective than positive framing (Maheswaran and Meyers-

Levy 1990). On the other hand, previous research suggests that if message claims predominate, then, in line with the well-documented negativity effect (e.g., Ahluwalia, Burnkrant, and Unnava 2000;

Herr, Kardes, and Kim 1991), negative framing is more effective than positive framing.

According to popular models of persuasion such as the Heuristic Systematic Model (e.g.,

Chaiken, Liberman, and Eagly 1989), one factor that determines whether message claims or heuristics predominate in persuasion is the level of processing-motivation. When the level of processingmotivation is low, persuasion is more likely to be determined by simple heuristics than by a careful scrutiny of the message claims. When the level of processing-motivation is high, consumers are likely to engage in systematic processes where they scrutinize the claims in greater detail since they care more about making accurate judgments (see, Jain and Maheswaran 2000 for persuasion in contexts that involve biased judgments). Thus, persuasion under these contexts is more likely to be determined by the cogency of the message claims than by simple heuristics. Next, we discuss how processingopportunity is likely to interact with processing-motivation in determining the relative impact on

persuasion of heuristics vis-à-vis message claims in message framing.

Low Processing-Motivation and Message Framing . Under conditions of low processingmotivation, one factor that has been found to determine the impact of a specific heuristic on

6 persuasion is its accessibility in memory (see, e.g., Chaiken, Wood, and Eagly 1996). Accessibility, in turn, could be affected by the level of processing-opportunity. For example, Roskos-Ewoldsen and

Fazio (1992) manipulated processing-opportunity by varying the number of items in their dependent measure and found that heuristics related to source-likeability become accessible and impact persuasion at higher than at lower levels of processing-opportunity. Similarly, the cognitive-response data reported in Wright (1974) suggest that when processing-motivation is low, heuristics related to the means used by the source are more accessible at higher than at lower levels of processingopportunity. These findings suggest that, in the context of message framing, when processing motivation is low, heuristics related to valence of the message frame are likely to become accessible and impact persuasion more at higher rather than lower levels of processing-opportunity. Since these cognitions are less favorable for negative compared to positive framing, negative framing is likely to be less effective than positive framing when processing-motivation is relatively low and processingopportunity is relatively high. More formally,

H1a: When the level of processing motivation is low and that of processing-opportunity is high, negative framing is likely to be less effective than positive framing.

Under conditions of low processing-motivation, heuristics based on simple evaluative thoughts arising from a low-effort scrutiny of the message claims can also impact persuasion. For example, in a study by Kisielius and Sternthal (1984), respondents read claims pertaining to a new brand of shampoo at different levels of processing-opportunity. At low levels of processing-opportunity, the message claims were found to have a bigger impact on persuasion; at higher levels of processing-opportunity,

non-message related cues had a bigger impact. Petty and Wegener (1999) term this phenomenon

7 where claims affect persuasion under low levels of processing-motivation as the quantitative-effect.

They argue that this phenomenon occurs when heuristics related to non-message factors are not highly accessible, which, based on Roskos-Ewoldsen and Fazio (1992) and Wright (1974) is likely to be the case when the level of elaboration is low, that is, when both motivation and opportunity are relatively low. Therefore, in the context of message framing, when levels of processing-motivation and processing-opportunity are both relatively low, a low-effort scrutiny of the message claims is likely to yield accessible claims-related heuristics. Since these heuristics focus on the message claims, based on the negativity effect, the heuristics are likely to favor negative framing over positive framing. More formally,

H1b: When the level of processing-motivation is low and that of processing-opportunity is also low, negative framing is likely to be more effective than positive framing.

Note that, together, hypotheses 1a and 1b are consistent with the findings reported in Shiv et al.

(1997). Note also that hypothesis 1a is consistent with the findings reported in the low motivation conditions of previous research on message framing.

High Processing-Motivation and Message Framing . As discussed earlier, message claims are likely to prevail over heuristics when the level of motivation is high. According to popular models of persuasion, this proposition is valid only when the opportunity to engage in a systematic mode of processing is also high. However, this qualifier that higher levels of processing-opportunity are necessary for systematic processes to occur under conditions of high processing-motivation has not received sufficient empirical support (see Chaiken 1987, p. 11; Chaiken et al. 1989, p. 223). Research in persuasion and impression formation suggests otherwise. For example, the findings reported in

Wright (1974) suggest that under conditions of high processing-motivation, the extent of cognitive

8 elaboration was not significantly different across different levels of processing-opportunity. Similarly,

Webster, Richter, and Kruglanski (1996), in a piece of research on impression formation found that the extent of cognitive elaboration was affected only under conditions of low motivation—greater elaboration when the processing-opportunity was high than when it was low. Under conditions of high processing-motivation, the level of cognitive elaboration was high, irrespective of the level of the processing-opportunity factor. These findings suggest that systematic processes are likely to occur whenever processing-motivation is high, regardless of levels of processing-opportunity.

1

In the context of message-framing, what the above discussion implies is that message claims are likely to have a bigger impact on persuasion than heuristics when processing-motivation is high, irrespective of the level of processing-opportunity. As a result, based on the negativity-effect, negative framing is likely to be more effective than positive framing, a prediction that is consistent with findings in the high motivation conditions of previous research on message framing. More formally,

H2: Under conditions of high processing-motivation, negative framing is likely to be more effective than positive framing, irrespective of the level of processing- opportunity.

EXPERIMENT 1

Although experiment 1 was similar to the studies reported in Shiv et al. (1997) in that it tested the hypotheses using comparative advertising frames, it was also different in several respects. First, instead of using choice as in Shiv et al. (1997), experiment 1 used attitude judgments, a more traditional measure of persuasion. Second, the processing-opportunity factor was manipulated in Shiv

1

The empirical evidence that we present in this research is consistent with this conclusion. However, it is quite possible that we are dealing with an issue of calibration both in our research and in the previous research cited here to arrive at this conclusion. We highlight this issue in our general discussion section.

9 et al. (1997) by having or not having a cognitive response measure following message exposure. In experiment 1, the processing-opportunity factor was manipulated by varying the level of cognitive load during message exposure. Third, to be in tune with prior work on message framing (e.g., Block and Keller 1995), additional manipulation and confounding checks were included in this experiment.

Finally, additional measures were collected to test some of the key arguments in our conceptualization including those related to the extent of cognitive elaboration and to the accessibility of frame-related heuristics.

Method

Design and Procedure. Experiment 1 used a 2 (Processing-Motivation: Low vs. High) X 2

(Processing-Opportunity: Low vs. High) X 2 (Framing: Negative vs. Positive) between-subjects design. Two hundred and fifteen undergraduate students from a large mid-western university were randomly assigned to one of eight experimental conditions. Each respondent was given a booklet that contained instructions on the cover page including those intended to manipulate the processingmotivation factor. They were then asked to memorize a number, a task that was intended to manipulate the processing-opportunity factor. The stimulus was then presented. The stimulus contained a persuasive message for Airline A that compared its on-time performance with Airline B. The stimulus also contained additional information about the airlines’ in-flight amenities. Subsequently, the following set of measures were presented: cognitive responses, attitude judgments, recall of the memorized number, manipulation check for the processing-motivation factor, manipulation check for the framing factor, and, finally, checks for potential confounds. (Note that the processing-opportunity manipulation persisted until after participants rated their attitudes toward Airline A. This procedure was adopted in light of findings reported in Shiv et al. [1997] suggesting that attitude judgments, by

10 themselves, can activate elaborate processing and enhance the accessibility of frame-related heuristics.)

The processing-motivation manipulation was adapted from Chaiken and Maheswaran (1994) and Sengupta, Goodstein, and Bonniger (1997). In the high processing-motivation conditions, the cover page stated: “As participants in this survey, your opinions are extremely important and will be analyzed individually by us. Thus, your individual opinion will have tremendous implication for this research.” In the low processing-motivation conditions, the cover page stated: “As participants in this survey, your opinion will be averaged with those of other participants, and will be analyzed at the aggregate level by us. Thus, your individual opinion will not have much of an implication for this research.” In addition, respondents were told that their name would be placed in a lottery. In the high processing-motivation conditions, they were told that the winner of the lottery will get to fly, free of cost, one of the airlines featured in the stimulus ($300 worth); in the low-processing-motivation conditions, they were told that the winner will get to rent a car free ($300 worth).

The processing-opportunity factor was manipulated by having respondents memorize either a seven-digit number (low processing-opportunity conditions) or a two-digit number (high processingopportunity conditions). The framing factor was manipulated in the stimulus as follows (negative framing in parenthesis):

We have been claiming all long that Airline A is better than B (B is worse than A) on on-time performance. Flying A (B) means fewer (more) of those endless, frustrating waits for you and those expecting you at your destination. It also means being on-time (late) for your appointments. And no more (more) missed flights.

A footnote was included to reinforce the claims (identical in both the framing conditions):

J. D. Power and Associates on-time performance index based on a survey of 6800 fliers (100 represents the average, higher numbers are better): A: 110; B: 97

11

Following the persuasive message, additional information was presented to all respondents:

We also need to tell you that J. D. Power and Associates reported the following inflight amenities indices (which include comfort, quality of the food, etc.) for the two airlines: B: 107; A: 94

Measures.

Participants’ cognitive responses were collected by having them report whatever thoughts went through their minds while reading Airline A’s message. Attitude toward Airline A was measured on four seven-point items anchored by bad/good, not likable/likable, undesirable/desirable, and useless/useful (α = .94). To assess the success of the processing-motivation manipulation, respondents were asked to indicate on three disagree (1)/agree (7) scales the extent to which Airline

A’s persuasive message and the information presented after the message were interesting, involving, and personally relevant (α = .88 for the persuasive message and .92 for the information presented after

Airline A’s message).

Our success at manipulating the framing factor was assessed as in Block and Keller (1995) and

Maheswaran and Meyers-Levy (1990). Respondents were asked to indicate on seven-point scales the extent to which Airline A’s persuasive message stressed the negative implications of flying the competing Airline B, and the extent to which the message stressed the positive implications of flying itself. Finally, three confounding-check measures used by Block and Keller (1995) were included.

Participants were asked to rate the information presented in Airline A’s message on seven-point measures anchored by not at all credible/very credible, difficult to comprehend/easy to comprehend, and contained little information/contained a lot of information.

Results

12

Manipulation Checks . The two indices assessing the motivation manipulation both revealed only main effects of processing-motivation. Respondents’ ratings were higher when the processingmotivation was high than when it was low for both Airline A’s persuasive message (

Ms = 4.27 and

3.23 respectively; F (1, 207) = 29.25, p < .0001,

2

= .12) and for the information presented after

Airline A’s message ( Ms = 4.21 and 3.32 in the high and low processing-motivation conditions, respectively; F (1, 207) = 15.00, p < .0001,

2

= .06).

The two indices assessing the framing manipulation both revealed only main effects of framing. Respondents rated the extent to which the message stressed the negative implications of flying Airline B to be higher in the negative frame condition ( M = 5.92) than in the positive frame condition ( M = 4.81; F (1, 206) = 34.61, p < .0001,

2 = .14). They also rated the extent to which the message stressed the positive implications of flying Airline A to be lower in the negative frame condition ( M = 4.33) than in the positive frame condition ( M = 5.47; F (1, 206) = 25.42, p < .0001,

2

= .10).

To assess the success of manipulating the processing-opportunity factor, an independent pretest was carried out with 42 respondents from the same population as the main experiment. The pretest respondents were randomly assigned to one of two processing-opportunity conditions and the procedure paralleled that used in the main experiment. After being exposed to the stimulus and reporting cognitive responses, respondents were asked to rate on three very low (1)/very high (7) scales the extent to which they deliberated, the time they spent thinking, and the amount of attention they paid while going through Airline A’s advertising message (α = .91). An ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of processing-opportunity ( F (1, 41) = 20.25

, p < .0001), and none of the other treatment effects were significant. The ratings of the extent of cognitive elaboration were higher in the high processing-opportunity condition ( M = 5.11) than in the low processing-opportunity condition ( M

= 3.73).

13

Finally, to rule out potential confounds, respondents had been asked to indicate how credible, how easy to comprehend, and how informative Airline A’s persuasive message was. Separate

ANOVAs on these variables revealed no significant treatment effects (F < 1), suggesting that our treatments were not confounded with the above variables. Thus, the manipulation and confounding checks suggest that the intended factors were manipulated successfully.

Attitudes . As indicated in table 2, an ANOVA performed on subjects’ attitudes toward Airline

A revealed a marginally significant main-effect of processing-motivation ( F (1, 206) = 2.80, p < .08,

2

= .01). This main effect was qualified by (1) a significant processing-motivation by framing interaction ( F (1, 206) = 5.07, p < .03,

2

= .02), (2) a marginally significant processing-motivation by processing-opportunity interaction ( F (1, 206) = 3.25, p < .07,

2

= .01), and (3) a significant processing-motivation by processing-opportunity by framing interaction ( F (1, 206) = 6.24, p < .01,

2

= .03). In addition, there was a significant processing-opportunity by framing interaction ( F (1, 206) =

4.98, p < .03,

2 = .02).

_________________________________________

Insert table 2 about here

_________________________________________

The pattern of results in the low processing-motivation conditions was in line with our conceptualization. When processing-opportunity was relatively low, attitude toward Airline A was higher in the negative frame condition ( M = 5.20) than in the positive frame condition ( M = 4.52; F (1,

206) = 3.94, p < .05,

2

= .02). When processing-opportunity was relatively high, attitude toward

Airline A was lower in the negative frame condition ( M = 3.79) compared to the positive frame condition ( M = 4.75; F (1, 206) = 7.49, p < .007,

2

= .03). Thus, both hypotheses 1a and 1b were supported.

14

The results in the high processing-motivation conditions were also consistent with our conceptualization. As shown in table 2, under both levels of the processing-opportunity factor, attitude toward Airline A was higher when the message was framed negatively than when it was framed positively. When processing-opportunity was relatively low, attitude toward Airline A was higher, at a marginal level of significance, in the negative frame condition ( M = 5.16) compared to the positive frame condition ( M = 4.54; F (1, 206) = 3.24, p < .07,

2 = .01). When processing-opportunity was relatively high, attitude toward Airline A was again higher in the negative frame condition ( M = 5.23) compared to the positive frame condition ( M = 4.52; F (1, 206) = 4.19, p < .05,

2

= .02). Thus, hypothesis 2 was also supported.

Cognitive Response Data . The cognitive responses were coded by an independent judge for the total number of thoughts and the total number of frame-related thoughts. The pattern of results on the total number of thoughts, an indicator of the extent of cognitive elaboration, was consistent with our conceptualization (see table 2 for the means across the various conditions and for the ANOVA results). Planned contrasts revealed that compared to the low processing-motivation/low processingopportunity condition ( M = 2.35), the total number of thoughts was higher when processingopportunity was enhanced ( M = 3.21; ( F (1, 207) = 11.76, p < .0007,

2 = .05). Further, the total number of thoughts in the high processing-motivation conditions was no different across the two levels of processing-opportunity ( Ms = 3.81 and 4.00 in the low and high processing-opportunity conditions, respectively; F < 1), but was significantly higher than the total number of thoughts in the low processing-motivation/low processing-opportunity conditions. For example, the lower of the two means in the high processing-motivation conditions (i.e., that in the high processing-motivation/low processing-opportunity conditions; M = 3.81) was significantly higher than the means in the low processing-motivation/low processing-opportunity conditions ( M = 2.35; ( F (1, 207) = 35.16, p <

15

.0001,

2 = .12).

An examination of the overall pattern of results on the number of frame-related thoughts yields a noteworthy finding (see table 2 for the means across the various conditions and for the ANOVA results). Means on the number of frame-related thoughts, an indicator of the accessibility of framerelated heuristics, were relatively low and no different across the positive frame conditions ( F < 1). It is quite possible that the reason for these results is that the valence of the message frame is less of an issue with positive than with negative framing. The results in the negative frame conditions were consistent with our conceptualization. When processing-motivation was relatively low, the number of frame-related thoughts was lower in the low processing-opportunity condition ( M = .25) than in the high processing opportunity condition ( M = 1.11; F (1, 207) = 14.13, p < .0002,

2

= .05). Incidentally, the number of frame-related thoughts was relatively high in the high processing-motivation/negative frame conditions ( M = .93 in both the low and high processing opportunity conditions; F < 1). These results, together with corresponding results on attitudes, suggest that frame-related heuristics were accessible when processing-motivation was high, but that these heuristics had a minimal impact on attitudes compared to the message claims.

Discussion

The results on brand attitude judgments were consistent with our predictions. Further, our results in the low processing-motivation conditions mirrored those reported in Shiv et al. under conditions of low processing-motivation. Our results in the high processing-motivation conditions mirrored those reported in previous research on message framing. Our findings also provide some insights into the similarities and differences between the effects of processing-motivation and processing-opportunity. Our results on the total number of thoughts suggest that these two factors are

16 similar in terms of the extent of cognitive elaboration they engender. They are also similar in that both influence the accessibility of frame-related heuristics. Despite these similarities, our results on the total number of frame-related thoughts, in conjunction with those on brand attitudes, suggest that the following. Compared to conditions of low processing-motivation/low processing opportunity, an increase in processing-opportunity increases the accessibility as well as the subsequent impact on attitudes (i.e., the diagnosticity) of frame-related heuristics. An increase in processing-motivation, on the other hand, increases the accessibility of these heuristics, but does not increase their subsequent impact on attitudes (i.e., their diagnosticity).

EXPERIMENT 2

There were several factors related to experiment 1 that motivated our design for experiment 2.

First, experiment 1 manipulated the framing factor by using comparative advertising frames, which is not the way framing has traditionally been manipulated in the literature. Experiment 2 used a traditional manipulation of framing with messages that stressed the benefits of following some recommendations (positive framing) or the costs of not following them (negative framing). Second, in experiment 1, cognitive responses were collected after message exposure and prior to attitude judgments. It is quite possible that reporting these cognitive responses altered the nature of processing after message exposure in experiment 1. In experiment 2, we excluded the cognitive response measure, and instead used scale measures, presented after measuring attitude judgments, to assess the extent of cognitive elaboration. Third, we included scale measures to assess not only the accessibility of frame-related heuristics, but also their diagnosticity (i.e., the extent of their subsequent impact on brand attitudes). Finally, to increase the validity of our findings, the stimulus featured a detergent rather than airlines.

17

Method

Design and Procedure. Experiment 2 used a 2 (Processing-Motivation: Low vs. High) X 2

(Processing-Opportunity: Low vs. High) X 2 (Framing: Negative vs. Positive) between-subjects design. Two hundred and eighty-seven undergraduate students from the same population as experiment 1 were randomly assigned to one of eight experimental conditions, and the procedure paralleled that used in experiment 1. The framing factor was manipulated as in prior research on message framing without any reference to a comparison brand (negative framing in parenthesis):

Now Consumer Reports validates our claims about our Color-Guard 500

TM protection. So what does all this mean to you? By (not) using Detergent A, your clothes will look new (old) even after many (just a few) washes. And by (not) using Detergent A, your blacks will look black (gray), your bold reds will remain vivid (will be faded). Just think of the money you will stand to gain (lose) by not having (by having) to replace your favorite clothes. Remember that you stand to gain (lose) all these important benefits if you use (fail to use) Detergent A.

The opening claim was reinforced in both the frames by a footnote stating:

Consumer Reports (December 2001) color-guard protection index (100 represents the average, higher numbers are better) for Detergent A: 120.

The sequence in which the various measures were presented was: attitude judgments, recall of the memorized number, extent of cognitive elaboration, accessibility of frame-related heuristics, diagnosticity of frame-related heuristics, manipulation check for the processing-motivation factor, manipulation check for the framing factor, and finally, checks for potential confounds.

18

Measures. In addition to the measures used in experiment 1, the extent of cognitive elaboration was assessed in experiment 2 by asking respondents to indicate on very low (1)/ very high (7) scales the extent to which they thought about, the time they spent thinking about, and the amount of attention they paid to the issues arising from the ad (α = .87). The accessibility of frame-related heuristics was assessed on a disagree (1)/agree (7) scale by asking respondents to indicate the extent to which they thought about how fair or unfair Detergent A was in the way it presented its claims. Similarly, the diagnosticity of these heuristics was assessed by asking respondents to indicate the extent to which their attitudes toward Detergent A was influenced by the way in which the claims were presented.

Results

Manipulation Checks. An ANOVA with respondents’ ratings of how involved they were when reading the Detergent A’s persuasive message revealed a significant main effect of processingmotivation ( F (1, 279) = 76.62, p < .0001,

2

= .21) and none of the other treatment effects were significant. Ratings of involvement were higher under conditions of high processing-motivation ( M =

4.19) than low processing-motivation ( M = 2.93). Further, the two indices assessing the framing manipulation both revealed only main effects of framing. Respondents rated the extent to which the message stressed the negative implications of not using Detergent A to be higher in the negative frame condition ( M = 5.63) than in the positive frame condition ( M = 3.12; F (1, 279) = 207.9, p < .0001,

2

= .42). They also rated the extent to which the message stressed the positive implications of using

Detergent A to be lower in the negative frame condition ( M = 4.37) than in the positive frame condition ( M = 6.06; F (1, 279) = 101.5, p < .0001,

2 = .26). Finally, as in experiment 1, separate

ANOVAs on the three confounding-check variables revealed no significant treatment effects ( F < 1).

19

Attitudes . As indicated in table 3, an ANOVA with attitudes toward Detergent A as the dependent variable revealed a significant main-effect of framing ( F (1, 279) = 4.26, p < .04,

2

= .02).

This main effect was qualified by: (1) a significant processing-motivation by framing interaction ( F (1,

279) = 5.34, p < .02,

2 = .03), (2) a significant processing-opportunity by framing interaction ( F (1,

279) = 4.43, p < .04,

2 = .02), and (3) a marginally significant processing-motivation by processingopportunity by framing interaction ( F (1, 279) = 3.01, p < .08,

2

= .01).

________________________________________

Insert table 3 about here

________________________________________

The pattern of results in the low processing-motivation conditions was similar to those obtained in experiment 1. When processing-opportunity was relatively low, attitude toward Detergent

A was higher, at a marginal level of significance, in the negative frame condition ( M = 5.03) than in the positive frame condition ( M = 4.49; F (1, 279) = 3.02, p < .08,

2

= .01). When processingopportunity was relatively high, attitude toward Detergent A was lower in the negative frame condition ( M = 4.49) compared to the positive frame condition ( M = 5.10; F (1, 279) = 4.25, p < .04,

2

= .02). Thus, hypotheses 1a and 1b were supported.

The results in the high processing-motivation conditions paralleled those in experiment 1. As shown in table 3, under both levels of the processing-opportunity factor, attitude toward Detergent A was higher when the message was framed negatively than when it was framed positively. When processing-opportunity was relatively low, attitude toward Detergent A was higher in the negative frame condition ( M = 5.31) compared to the positive frame condition ( M = 4.60; F (1, 279) = 5.82, p <

.02,

2

= .03). When processing-opportunity was relatively high, attitude toward Detergent A was again higher in the negative frame condition ( M = 5.35) compared to the positive frame condition ( M

= 4.75; F (1, 279) = 4.08, p < .04,

2

= .01). Thus, hypothesis 2 was also supported.

20

Extent of Cognitive Elaboration.

The results on the scale measures relating to the extent of cognitive elaboration were consistent with our conceptualization (see table 3 for the means across the various conditions and for the ANOVA results). Planned contrasts revealed that compared to the low processing-motivation/low processing-opportunity condition ( M = 2.93), the extent of cognitive elaboration was higher when processing-opportunity was enhanced ( M = 3.52; ( F (1, 273) = 9.36, p <

.002,

2

= .04). Further, the extent of elaboration in the high processing-motivation conditions was no different across the two levels of processing-opportunity ( Ms = 4.04 and 4.00 in the high and low processing-opportunity conditions, respectively; F < 1), but was significantly higher than the extent of elaboration in the low processing-motivation/low processing-opportunity conditions. For example, the lower of the two means in the high processing-motivation conditions (i.e., that in the high processingmotivation/low processing-opportunity conditions; M = 4.00) was significantly higher than the mean in the low processing-motivation/low processing-opportunity conditions ( M = 2.93; ( F (1, 273) =

29.51, p < .0001,

2 = .09).

Accessibility and Diagnosticity of Frame-Related Heuristics.

The results on the scale measures related to the accessibility and the diagnosticity of frame-related heuristics are presented in table 2. As in experiment 1, the means on accessibility were relatively low and no different across the positive frame conditions ( F < 1), again suggesting that the valence of the message frame is less of an issue with positive than with negative framing. The results in the negative frame conditions were consistent with our conceptualization. At low levels of processing-motivation, the extent to which respondents thought about the frame was lower in the low processing-opportunity condition ( M = 3.64) than in the high processing opportunity condition ( M = 4.41; F (1, 279) = 4.69, p < .03,

2

= .01). Also, the means were relatively high and no different in the high processing-motivation/negative frame conditions ( M

21

= 4.49 and 4.47 in the low and high processing-opportunity conditions, respectively; F < 1).

The results on the diagnosticity of frame-related heuristics in the negative frame conditions paralleled those related to the accessibility of these heuristics under conditions of low but not high processing-motivation. At low levels of processing-motivation, the extent to which respondents thought that the frame influenced their attitudes was lower in the low processing-opportunity condition

( M = 3.36) than in the high processing opportunity condition ( M = 4.16; F (1, 279) = 5.03, p < .02,

2 =

.01). However, at high levels of processing-motivation, the means were relatively low across both levels of processing-opportunity ( M = 3.43 and 3.53 in the low and high processing opportunity conditions, respectively; F < 1). Together, the results on accessibility and diagnosticity of framerelated heuristics suggest the following. Compared to conditions where levels of processingmotivation and processing-opportunity are both low, varying the level of processing-opportunity affects both the accessibility and diagnosticity of these heuristics. On the other hand, varying the level of processing-motivation affects the accessibility but not the diagnosticity of these heuristics.

Discussion

Experiment 2 extends the findings of experiment 1 by using a more traditional framing manipulation and a different product category (detergents instead of airlines). Further, the cognitive response measure that was included in experiment 1 after message exposure was dropped in experiment 2 suggesting that the findings in experiment 1 were not an artifact of including this measure. Experiment 2 continued the process of providing insights into the similarities and differences between the effects of processing-motivation and processing-opportunity. Our results suggest that these two factors are similar in terms of the extent of cognitive elaboration they engender. They are also similar in that both influence the accessibility of frame-related heuristics. However, compared to

conditions of low processing-motivation/low processing opportunity, an increase in processing-

22 opportunity increases the accessibility as well as the diagnosticity of frame-related heuristics. An increase in processing-motivation, on the other hand, increases the accessibility of these heuristics, but does not increase their diagnosticity.

GENERAL DISCUSSION

The goal of this article was to resolve seemingly conflicting findings reported in previous work on message framing (e.g., Block and Keller 1995; Maheswaran and Meyers-Levy 1990; Rothman et al. 1993) and those reported in a recent piece of work by Shiv et al. (1997). We show, across two experiments, that a resolution to the seeming conflict lies in the way cognitive elaboration was manipulated by Shiv et al. (1997) and in previous research. We replicate the findings in Shiv et al.

(1997) when processing-motivation is low and the level of elaboration is manipulated using opportunity-related variables. Specifically, we find that negative framing is more effective than positive framing when processing-opportunity is low, but less effective than positive framing when processing-opportunity is high. We also show that if high elaboration is induced by motivation-related variables, negative framing tends to be more effective than positive framing, irrespective of the level of processing-opportunity, mirroring the findings reported in previous research on message framing.

Our findings related to the extent of elaboration, and to the accessibility and diagnosticity of frame-related heuristics shed some light on the potential causes for the observed pattern of results.

First, our findings suggest that when processing-motivation and processing-opportunity are both low, frame-related heuristics are relatively inaccessible and the focus of processing is predominantly on the message claims. When the focus is on message claims, the negativity effect suggests that negatively framed information ought to be more persuasive than positively framed information, which is the

pattern we observe under these conditions. Second, when processing-motivation remains low, an

23 increase in processing-opportunity increases cognitive elaboration, which, in turn increases the accessibility as well as the subsequent impact on attitudes (i.e., the diagnosticity) of frame-related heuristics. Since these heuristics are less favorable for negative than for positive framing, their enhanced impact on persuasion accounts for reversal that we observe under conditions of low processing-motivation and high processing-opportunity. Finally, an increase in processing-motivation from low levels of processing-motivation and processing-opportunity increases cognitive elaboration, which, in turn increases the accessibility of frame-related heuristics, irrespective of the level of processing-opportunity. But this increased accessibility does not translate to an increase in the subsequent impact on attitudes (i.e., the diagnosticity) of these heuristics. Rather, our findings suggest that when processing-motivation is high, message claims tend to have a bigger impact on persuasion than the accessible frame-related heuristics. With the focus being on the message claims, in line with the negativity effect, negative framing ought to be more effective than positive framing, which is the pattern we observe in the high processing-motivation conditions.

Limitations and Further Research

This study examined the effects of message framing with only a relatively short time span intervening between message-exposure and judgments. It will be important to examine the robustness of these findings as the length of time increases to levels more closely associated with typical purchase cycles. Secondly, our study lacked much of the richness that surrounds real world brand choices. We did not examine the effects of message framing on choices among brands, which is typically what consumers do in real-world decision-making tasks. Further, our respondents had only limited information upon which to base their judgments. It is quite possible that as more of the complexities of

24 the real world are considered, further refinement to our theorizing and conclusions will be needed.

A third important limitation is that we examined the moderating role of processing-opportunity by engendering only two levels of this factor. Our findings suggest that systematic processing occurs at higher levels of processing-motivation, irrespective of the level of the processing-opportunity factor.

This is contrary to popular models of persuasion such as the Heuristic Systematic Model, which posit that when processing-motivation is high, higher levels of processing-opportunity are necessary for systematic processing to occur. It is quite possible that the task of memorizing a seven-digit number to engender lower levels of processing-opportunity did not sufficiently impair processing-resources, and that adequate resources were still available for respondents to engage in systematic processing. Future research needs to delve further into this issue by examining the effectiveness of negatively versus positively framed information at very low, moderately low, and high levels of processing-opportunity

(see, Suri and Monroe forthcoming). It is quite possible that systematic processes, which presumably occurred in our high-motivation conditions, would not occur at very low levels of processingopportunity, giving rise to a pattern of results that is different than the one observed in our research.

Finally, we examined the relative effectiveness of negative framing compared to positive framing, a research topic that has received considerable attention in recent years. We resolved conflicting findings in the literature by identifying two factors, processing-opportunity and processingmotivation, that differentially moderate the relative impact of message claims and frame-related heuristics on persuasion. Future research also needs to examine the moderating role of processingopportunity and processing-motivation on other non-message heuristics that have been examined in the persuasion literature. These include source credibility, deceptive messages, fear appeals, borrowed-interest appeals (e.g., Campbell 1995), and persuasion-knowledge (e.g., Campbell and

Kirmani 2000). Examining these issues will provide researchers as well as marketers with richer insights into the effects of such variables on persuasion.

25

REFERENCES

Ahluwalia, Rohini, Robert E. Burnkrant, and Rao H. Unnava (2000), “Consumer Response to

Negative Publicity: The Moderating Role of Commitment,” Journal of Marketing Research , 37

(May), 203-214.

Block, Lauren G. and Punam Keller (1995), “When to Accentuate the Negative: The Effects of

Perceived Efficacy and Message Framing on Intentions to Perform a Health-Related

Behavior,” Journal of Marketing Research , 32 (May), 192-203.

Campbell, Margaret C. (1995), “When Attention-Getting Advertising Tactics Elicit Consumer

Inferences of Manipulative Intent: The Importance of Balancing Benefits and Investments,”

Journal of Consumer Psychology , 4 (3), 225-254.

Campbell, Margaret C. and Amna Kirmani (2000), “Consumers' Use of Persuasion Knowledge: The

Effects of Accessibility and Cognitive Capacity on Perceptions of an Influence Agent,”

Journal of Consumer Research , 27 (June), 69-83.

Chaiken, Shelly (1987), “The Heuristic Model of Persuasion,” in Social Influence: The Ontario

Symposium (Vol. 5) , ed. Mark P. Zanna, James M. Olson, and Peter C. Herman, Hillsdale, NJ:

Erlbaum, 3-39.

Chaiken, Shelly, Akiva Liberman,and Alice H. Eagly (1989), “Heuristic and Systematic Information

Processing within and beyond the Persuasion Context,” in

Unintended Thought, ed. James. S.

Uleman and John A. Bargh, New York, NY: Guilford, 212-252.

Chaiken, Shelly and Durairaj Maheswaran (1994), “Heuristic Processing Can Bias Systematic

Processing: Effects of Source Credibility, Argument Ambiguity, and Task Importance on

Attitude Judgment,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 66 (March), 460-473.

Chaiken, Shelly, Wendy Wood, and Alice H. Eagly (1996), “Principles of Persuasion,” in Social

Psychology: Handbook of Basic Principles , ed. E. Tory Higgins and Arie W. Kruglanski, New

York, NY: Guilford, 702-742.

Herr, Paul M., Frank R. Kardes and John Kim (1991), “Effects of Word-of-Mouth and Product

26

Attribute-Information on Persuasion: An Accessibility-Diagnosticity Perspective,” Journal of

Consumer Research , 17 (March), 454-462.

Jain, Shailendra P. and Durairaj Maheswaran (2000), “Motivated Reasoning: A Depth-of- Processing

Perspective, Journal of Consumer Research , 26 (March), 358-371.

Kisielius, Jolita and Brian Sternthal (1984), “Detecting and Explaining Vividness Effects in

Attitudinal Judgments,”

Journal of Marketing Research , 21 (February), 54-64.

Levin, Irwin P., Sandra L. Schneider, and Gary J. Gaeth (1998), “All Frames Are Not Created Equal:

A Critical Review of Differences in Valence Framing Effects,”

Organizational Behavior and

Human Decision Processes , 76 (November), 149-188.

Maheswaran, Durairaj and Joan Meyers-Levy (1990), “The Influence of Message Framing and Issue

Involvement,”

Journal of Marketing Research , 27 (August), 361-367.

Petty, Richard E. and Duane T. Wegener (1999), “The Elaboration Likelihood Model: Current Status and Controversies,” in

Dual-Process Theories in Social Psychology , ed. Shelly Chaiken and

Yaacov Trope, New York, NY: Guilford, 37-72.

Rothman, Alexander J., Peter Salovey, Carol Antone, Kelli Keough, and Chloe Drake Martin (1993),

“The Influence of Message Framing on Intentions to Perform Health Behaviors,”

Journal of

Experimental Social Psychology , 29 (September), 408-433.

Rothman, Alexander J. and Peter Salovey (1997), “Shaping Perceptions to Motivate Healthy

Behavior: The Role of Message Framing,”

Psychological Bulletin , 121 (January), 3-19.

Roskos-Ewoldsen, David R. and Russell H. Fazio (1992), “The Accessibility of Source Likability as a

Determinant of Persuasion,”

Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin , 18 (February), 19-25.

Sengupta, Jaideep, Ronald C. Goodstein, and David S. Boninger (1997), “All Cues Are Not Created

27

Equal: Obtaining Attitude Persistence Under Low-Involvement Conditions,” Journal of

Consumer Research , 23 (March), 351-361.

Suri, Rajneesh and Kent B. Monroe (forthcoming), “The Effects of Time Constraints on Consumers’

Judgments of Prices and Products,” Journal of Consumer Research .

Shiv, Baba, Julie A. Edell, and John W. Payne (1997), “Factors Affecting the Impact of Negatively versus Positively Framed Ad Messages,”

Journal of Consumer Research , Vol. 24 (December),

285-94.

Webster, Donna M., Linda Richter, and Arie W. Kruglanski ,

(1996), “On Leaping to Conclusions

When Feeling Tired: Mental Fatigue Effects on Impressional Primacy,”

Journal of

Experimental Social Psychology , 32 (March), 181-95 .

Wright, Peter (1974), “Analyzing Media Effects on Advertising Responses,”

Public Opinion

Quarterly , 38 (Summer), 192-205.

28

TABLE 1

RECENT SELECTED STUDIES ON MESSAGE FRAMING RELEVANT TO THIS RESEARCH

Authors

Block and

Keller

(1995)

Maheswaran and Meyers-

Levy (1990)

Rothman et al. (1993)— experiment

1

Shiv et al.

(1997)

Framing Effects

Negative framing more effective than positive framing when the level of elaboration is high; negative framing as effective as positive framing when the level of elaboration is low.

Negative framing more effective than positive framing when the level of elaboration is high; negative framing less effective than positive framing when the level of elaboration is low.

Negative framing more effective than positive framing when the level of elaboration is high; negative framing less effective than positive framing when the level of elaboration is low.

Negative framing less effective than positive framing when the level of elaboration is high; negative framing more effective than positive framing when the level of elaboration is low.

Comments

Cognitive elaboration manipulated by varying the level of perceived efficacy, that is, the certainty with which adherence to recommendations in the message will lead to the desired outcome. The key dependent variables used were attitude judgments and behavioral intentions.

Framing manipulated by having the message focus on the benefits of following the recommendations (positive framing) or the costs of not following them (negative framing).

Cognitive elaboration manipulated by varying the level of personal relevance. The key dependent variables used were attitude judgments and behavioral intentions. Framing manipulated by having the message focus on the benefits of following the recommendations (positive framing) or the costs of not following them (negative framing).

Cognitive elaboration manipulated by varying the level of involvement with the issue being discussed (skin cancer), with women being more involved with the issue than men. The key dependent variable used was behavioral intentions. Framing manipulated by having the message focus on the benefits of following the recommendations (positive framing) or the costs of not following them (negative framing).

Cognitive elaboration manipulated by having respondents report (high elaboration) or not report (low elaboration) their cognitive responses after message exposure. The key dependent variable used was choice between the sponsoring and comparison brands. Framing manipulated by having the message focus on the positive consequences of choosing the advertised brand (positive framing) or the negative consequences of choosing the comparison brand (negative framing).

29

TABLE 2

MEANS (STANDARD DEVIATIONS) OF KEY DEPENDENT MEASURES (EXPERIMENT 1)

( n )

Attitudes

Cognitive elaboration

Framerelated thoughts

Low PM low PO

NF

(28)

Low PM low PO

PF

(27)

Low PM high PO

NF

(26)

Low PM high PO

PF

(26)

High PM low PO

NF

(27)

High PM low PO

PF

(28)

High PM high PO

NF

(27)

High PM high PO

PF

(26)

5.20

(1.19)

2.32

(0.77)

0.25

(0.58)

4.52

(1.55)

2.37

(1.11)

0.15

(0.36)

3.79

(1.32)

3.50

(0.81)

1.11

(1.30)

4.75

(0.79)

2.92

(1.32)

0.19

(0.80)

5.16

(1.29)

4.00

(1.30)

0.93

(1.11)

4.54

(1.53)

3.64

(1.39)

0.07

(0.38)

5.23

(0.78)

4.29

(1.83)

0.93

(1.24)

4.52

(1.42)

3.69

(1.54)

0.04

(0.19)

Significant effects

F value

PM

PM x F

PO x F

PM x PO

PM x PO x F

PM

PO

F

PM x PO

PO

F

PM x F

PO x F

PM x PO

PM x PO x F

2.80

5.07

4.98

a b a

3.25

b

6.24

a

41.24

a

8.50

a

4.08

a

3.81

a

3.63

a

35.22

a

2.62

b

3.43

b

4.21

a

2.92

b

PM = processing-motivation; PO = processing-opportunity; F = framing; NF = negative framing; PF = positive framing b

p < .10 a

p < .05

30

TABLE 3

MEANS (STANDARD DEVIATIONS) OF KEY DEPENDENT MEASURES (EXPERIMENT 2)

( n )

Attitudes

Cognitive elaboration

Frame accessibility

Frame diagnosticity

Low PM low PO

NF

(33)

Low PM low PO

PF

(34)

Low PM high PO

NF

(37)

Low PM high PO

PF

(36)

High PM low PO

NF

(37)

High PM low PO

PF

(37)

High PM high PO

NF

(38)

High PM high PO

PF

(35)

Significant effects

F value

5.03

(1.01)

3.11

(1.13)

3.64

(1.63)

3.36

(1.19)

4.49

(1.45)

2.76

(0.95)

3.56

(1.42)

3.56

(1.42)

4.49

(1.30)

3.68

(1.10)

4.41

(1.23)

4.16

(1.46)

5.10

(1.08)

3.36

(1.22)

3.64

(1.76)

3.00

(1.60)

5.31

(1.08)

4.06

(1.32)

4.49

(1.62)

3.43

(1.44)

4.60

(1.65)

3.91

(1.04)

3.57

(1.07)

3.35

(1.49)

5.35

(0.97)

4.17

(1.14)

4.47

(1.35)

3.53

(1.54)

4.75

(1.41)

3.90

(0.99)

3.57

(1.67)

3.29

(1.67)

F

PM x F

PO x F

PM x PO x F

PM

PO

F

PM x PO

F

4.26

a

5.34

a

4.43

a

3.01

b

34.00

a

5.40

a

4.07

a

4.03

a

14.45

a

F

PO x F

PM x PO x F

3.57

a

4.46

a

2.90

b

PM = processing-motivation; PO = processing-opportunity; F = framing; NF = negative framing; PF = positive framing b

p < .10 a

p < .05

Headings List

1) CONCEPTUAL FOUNDATION

2) Moderating Roles of Processing Motivation and Opportunity in Message Framing

3) Low Processing-Motivation and Message Framing.

3) High Processing-Motivation and Message Framing.

1) EXPERIMENT 1

2) Method

3) Design and Procedure.

3) Measures.

2) Results

3) Manipulation Checks.

3) Attitudes.

3) Cognitive Response Data.

2) Discussion

1) EXPERIMENT 2

2) Method

3) Design and Procedure.

3) Measures.

2) Results

3) Manipulation Checks.

3) Attitudes.

3) Extent of Cognitive Elaboration.

3) Accessibility and Diagnosticity of Frame-Related Heuristics.

2) Discussion

31

1) GENERAL DISCUSSION

2) Limitations and Further Research

32