TABLE OF CONTENTS

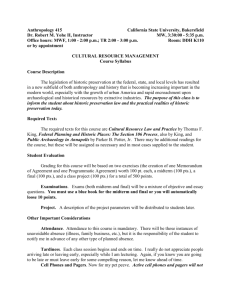

advertisement