Web-based spatial information system for coastal management and

advertisement

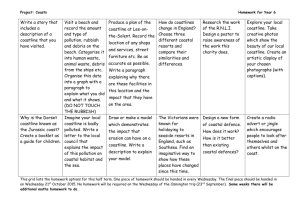

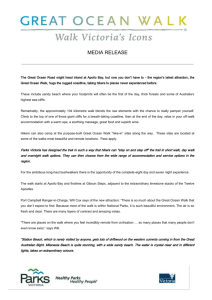

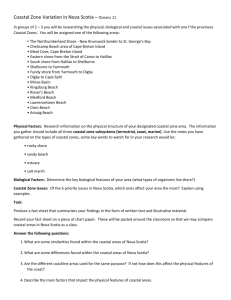

Web-based spatial information system for coastal management and governance in South Africa. Richard Knight1 and Martin P. Cocks2 1 Biodiversity and Conservation Biology (BCB) Department, University of the Western Cape, Private Bag X17, Bellville, 7535, email: rknight@uwc.ac.za 2 International Ocean Institute – Southern Africa, BCB Department, University of the Western Cape, Private Bag X17, Bellville, 7535, email: mcocks@uwc.ac.za Introduction: Information Sharing and Agenda 21 At the beginning of the 21st century it is becoming increasingly important that we are able to utilize the world’s resources in a sustainable way if society is to face a future. Few scientists and politicians do not accept that humans have been altering the world’s climates, or oare last amplifying a natural warming of the earth. Unfortunately developing countries will have the least capacity to adapt to climate changes, despite their minimal contribution to the problem and consequently the most to loss. As a consequence of both climate change and depletion of renewable global resources it is necessary that each country develop its own strategies to mitigate these environmental issues that affect global sustainability. National strategies nevertheless need to articulate with each in order to bring about the greatest synergy of benefits for the world and the Rio Earth Summit held in 1994 and the World Summit on Sustainable Development held in 2004 addressed such a need for integrating national responses. Arising from the Rio Earth summit was Agenda 21 of the Convention on Biological Diversity which recognized the critical role that information plays in being able to make accountable and scientifically rigourous decisions, permit wiser use of resources in manner that is more fairly distributed amongst the world’s population. Consequently “Sustainability” and “Equity” were defining concepts (reference) and Agenda 21 states “In sustainable development everybody is both a user and a provider of information” 1 and “The need for information arises at all levels from senior decision makers at national and international levels to grass-roots level and individual levels.” It therefore recognizes the urgency to bridge the information gap between those that have ready access to good quality, relevant up-to-date data and information and those that do not. Bridging this gap will have to be done by both increasing the quality and relevance of information and its open access to all levels of society. In this way virtually all Governments should be made more accountable for the decisions that they are making with respect to the environment. Coastal Environments As more of the World’s population are moving to the coast, together with most of the oceans and seas being an international commonage for exploitation of fish, and the coast lines being vulnerable to oil spills since the oceans still transport the majority of the world’s manufactured goods, this environment is especially important for sustainable and equitable management. Consequently the Department of Marine and Coastal Management of the South African government proactively engaged with these issues through the development of the South African Coastal Information Center (SACIC). SACIC provides up-to-date, relevant spatial information to department managers and the members of the public in order that more informed decisions can be made regarding the utilization of coastal resources and coastal conservation. The Internet and Implementing Agenda 21 In order for the data or information, which is needed for good governance at all of society to be effective, it should be well managed such that data/information 1. acquisition needs to be accurate, relevant and up-to-date, 2. management needs to be efficient and centralized to prevent unnecessary duplication and effort, 3. dissemination must to be to where it is needed to the widest audience. 2 The three above steps will be ineffective without providing the appropriate training in the collection, management and dissemination of the data /information. Developing an effective information strategy and delivery system that is accessible is the challenge for governments that are increasing required to provide such services to all levels society including thousands of managers and members of the public who are geographically dispersed and resourced with infrastructure. How is the South African government with its limited resources going to be able to implement the recommendations of Agenda 21? The Internet has been recognized as possibly playing a crucial role in all three management necessities mentioned above [reference?] and together with modern eLearning approaches to deliver the training needs. This paper analyses the Internet infrastructure and its projected growth together with providing working Internet-based solutions for the management and governance of two coastal issues, namely 1) An electronic transaction system for applying and granting of permits for vehicles to access the beach to selected user groups. 2) An electronic tracking system for the management of illegal structures (beach cottages) that have proliferated along the Wild Coast (the Transkei region of the Eastern Cape Province) Both applications are integrated into the South African Coastal Information CenterSACIC which is an interactive web-portal providing information about the South African coast in three broad areas, namely 1. Education and awareness material, 2. Information about sustainable development initiatives including various coastal projects 3. Provide spatial information useful to manager and the general public through Web Map Services (WMS) 3 Internet Penetration and Use in the African Context The development of SACIC, initiated in 2001 as an International Ocean Institute – southern Africa was to provide a public clearing house for coastal information, through a web portal. Since this time use of the Internet has expanded with increased bandwidths and lowered costs of bandwidth in most countries (South Africa remains the exception with exceptionally expensive bandwidth due to lack of competition in the telecommunications industry). Nevertheless the implementation of Agenda 21 Chapter 40 is largely being undertaken using the Internet and effectively enabling regulation and governance of environmental, social and economic activities through developing of an eGovernment solution. Despite the high prevailing costs of bandwidth and securing it in Africa the Internet will play an important role in the implementation of Agenda 21. Africa is the least connected continent with only 1.5% of the population having access to the Internet and this compares to a global average of 13.9% and North America and Europe at 67.4% and 35.5% Internet access respectively (Figure 1) 13.90% WORLD TOTAL 146.20% 48.60% Oceania / Australia 113.50% 10.30% Latin America/Caribbean 211.20% 67.40% North America Middle East 104.90% 7.50% 266.50% 35.50% Europe Asia Africa 151.90% 8.40% 164.40% 1.50% 198.30% 0.00% 50.00% Usage Growth 2000-2005 100.00% 150.00% 200.00% 250.00% 300.00% % Population with Internet access ) 4 Figure 1 Usage growth in the use of the Internet 2000 – 2005 and % of Population with Internet Access for various regions of the world. Statistics were taken from www.internetwordstats.com While the penetration of the Internet is low in Africa it has the world’s third highest usage growth. In the last five years Africa’s Internet usage grew 198.3% and only Middle East (266.5%) and Latin America and the Caribbean (211.2%) experienced more growth (Figure 1). As global bandwidths costs drop this will put pressure on local telecommunications to follow so that Africa will hopefully receive such benefits and this will stimulate more investment in Internet infrastructure. Rapid urbanization in Africa will likely mean more concentrated spatial demography that could also facilitate faster penetration of Internet usage. Within Africa, Zimbabwe, Lesotho, Cote d’Ivoire and Egypt have the greatest internet usage growth of > 500% in the last five years (Figure 2). South Africa has the second highest Internet availability on the African continent with Mauritius having the highest (Figure 2) but in terms of absolute numbers South Africa has seen an increase from 2.5 to 3.5 million in the last four years (Figure 3). South Africa Zimbabwe Zambia Uganda Tanzania Swaziland Nigeria Namibia Mozambique Mauritius Malawi Lesotho Kenya Egypt Cote d'Ivoire Botswana Angola 0.00% 200.00% 400.00% Use Growth (2000-2005) 600.00% 800.00% 1000.00% % Population with Internet Access Figure 2 Usage growth in the use of the Internet 2000 – 2005 and penetration into the population for selected African countries. Statistics were taken from www.internetwordstats.com. 5 4,000,000 8.00% 3,500,000 7.00% 3,000,000 6.00% 2,500,000 5.00% 2,000,000 4.00% 1,500,000 3.00% 1,000,000 Users (number) 2.00% 500,000 1.00% 0.00% 0 2000 2001 Users 2002 2003 % Population 2004 % Population (penetration) Figure 3 Increase in the total number and percentage of the population of Internet users in South Africa from 2000 – 2005. Statistics were taken from www.internetwordstats.com. Consequently the Internet is likely to becoming increasingly feasible for dissemination and managing information in South Africa and is likely to get to the same % penetration as the mobile phone telecommunications industry within five years. Coastal Management structures in South African Coastal Management in South Africa falls mostly within the responsibility of the Department of Environmental Affairs and Tourism (DEAT) and the Marine and Coastal Management (MCM) is the Branch tasked with this responsibility. The South African Government’s White Paper on Sustainable Coastal Development (Anon. 2000) lead to the establishment of a directorate of Integrated Coastal Management and Development within MCM with the following four sub-directorates: 1. Integrated Coastal Management, 2. Marine and Coastal Pollution Management, 3. Sustainable Livelihoods and Socio-Economic Development, 4. Subsistence Fisheries Management. 6 This White Paper also specifically identified the Internet to be used for information provision in order to further the aims of the above four sub-directorates and herein lies the role of SACIC which is specifically to disseminate information for the first three of the four sub-directorates. Funding for SACIC is currently in the second phase and has concentrated on projects that specifically help coastal managers in the Integrated Coastal Management and Development Directorate to make more informed decisions in coastal matters particularly those operating in a spatial context. Coastal Web Map Services (WMS) Central to SACIC developing decision support systems was the use of a Web Map Service. In the beginning these Web Map Services provided little more than basic map viewing (zooming, panning), making queries (identification and searches, both spatial and non-spatial) and printing maps with user-defined layers of information and at userdefined scales. While these services were useful the products remained little more than customizable maps. The first Generation SACIC Web Map Services were exclusively developed using Windows-based ESRI ARC IMS architecture for the map services (the actually GIS) and a front-end developed using HTML and Java Scripts. The Second Generation SACIC Web Map Services still used Windows-based ESRI ARC IMS but now used Java Server Pages to connect to the GIS and all scripting is done using XML. In this way both a faster and more robust WMS was delivered and allowed the first customization based on users inputs. Various “Map Themes” were developed so the user could use these to open up a specific view (or combination of layers) of the South African coast and this together with the ability to locally store various geographical scales as Book Marks meant much faster navigation with fewer key strokes. The strategy here was to provide as direct access to desired map products so as to reduce loads on the server and permit greater (and faster) access to the WMS. The current SACIC maps are based on our second generation technology, but in the meantime a third generation WMS has been deployed to provide “Shareable” Web Map Services – which includes both ESRI ARC IMS map services and the Open GIS Consortium (OGC) map services. The Sharable Architecture extends to users being able to annotate the maps, save map projects, prepare 7 some basic GIS layers, upload their own GIS layers or GPS points and extract layers of information clipped to their Area of Interest from the server. All of these functions can also be stored on the server and made accessible via your Browsers Book Marks (Favourites) and even emailed to other people as an accessible URL. The thirdgeneration WMS are opening up enormous opportunities for developing and sharing spatial information. In order to demonstrate how this is possible we discuss two system which use Web Map Services for making management decisions. The first is a system to help in the issue of permits for vehicle beach access along the South African coast. The second is a system to manage information about illegal structures (beach cottages) which have proliferated along Wild Coast (Eastern Cape) in South Africa. Management of vehicle access to beaches. In 1994 prohibition on vehicle access to beaches was declared as a general policy promulgated in terms of the Environment Conservation Act in the South African Government Gazette on 29 April 1994. This was due to the environmental damage that off road vehicles were causing to the coastline. Permits for vehicle access would have to be obtained from the relevant authority in the South African Coastal provinces. A need was identified to help managers to make informed and consistent decisions when granting or refusing permits. In order to do this a consultative process with stakeholders was engaged and from this a set of standardized (and scientifically defensible) criteria for allowing or refusing beach access for vehicles was identified (reference). This aspect of the project was undertaken by the GIS consulting firm GISCOE in combination with Anchor Consulting as Coastal Specialists. IOI-SA implemented the decision making analysis within a WMS and developed the mechanisms to apply, analyze and accept/reject permit applications. Initially four user groups were identified as having legitimate needs for having access to the beach using vehicles and these are 1. under the provisions of the Marine Living Resources Act, 8 2. for disabled persons, 3. for tour operators, 4. for recreational use (e.g. angling competitions). The coastline was then examined and four GIS coverages developed that show areas in which vehicle access is either strongly discouraged or may be allowed in terms of the four criteria. The final decision on whether access is allowed still remains with the manager concerned who has the greatest knowledge of local conditions. Here we demonstrate an Web Map Services, which uses these coverages and other GIS information to help the public apply for permits and mangers to make informed and consistent decisions when granting vehicle beach access permits. An example of using an Web Map Services to apply for a vehicle beach access permit In this hypothetical example we examine the case of Mr. André Cloete who lives in Noordkuil on the west coast of South Africa. Mr. Cloete has been successful in his application to collect drift kelp along the beaches near his hometown. However, he now needs to apply for a vehicle beach access permit so that he may access a beach on which he can collect the washed up kelp. We examine the steps he would under take to apply for his permit using the Web Map Services. This process may be divided into five main steps. These are; 1. Finding the area of interest, 2. Examining whether vehicle beach access is allowed in terms of the criterium for which he want to apply for the access (In this case he wishes to apply in terms of the marine living resources act), 3. Examining any additional GIS information, 4. Making an annotated map, 5. Sending in an application for a vehicle beach access permit. 9 Finding the area of interest Using the find location tab in the Web Map Services Mr. Cloete may choose Noordkuil from dropdown list of towns along the South African coast, which appear in the left hand window. The right hand map window then zooms into the area around the town of Noordkuil (Figure 4). To help Mr. Cloete to orientate himself the system automatically applies scanned 1:50 000 topographical map sheets as a backdrop to the map. Examining whether beach access is allowed in terms of the marine living resources act and additional GIS information Using the layers tab in the Web Map Services it is possible for Mr. Cloete to add or remove layers to or from his map. He may add a layer showing where vehicle beach access is allowed or strongly discouraged in terms of the marine living resources act (Figure 5). Using the legend tab he may call up a legend, which shows that a double red line indicates that beach access is discouraged along the section of the coastline nearest to Noordkuil (Figure 6). Figure 4 Web Map Services: finding a location 10 Figure 5 Web Map Services: adding new layers to the map Figure 6 Web Map Services: examining the legend, zooming out using the scale and using the pan tool 11 Figure 7 Web Map Services: using the measuring tool By examining other layers he can find out why vehicle beach access is discouraged. In this case if he adds the layer for coastal habits he can see by examining the legend that this area of beach is marked as a sensitive beach > 25km in length (Figure 6). If he wishes he can now zoom out a little to examine more of the coastline at once. This is done by adjusting the scale of the map by entering a new scale in the scale box below (Figure 6). He may now pan along the coastline by using the pan tool to look for an area of coast line where vehicle beach access is allowed (Figure 6). While panning along the coastline to the south of Noordkuil Mr. Cloete comes across an area of the coast which is mark with a double green line i.e. vehicle access to this section of the coast is allowed. He is not sure how long this stretch of coastline is however and whether it will be worth his will for collecting his kelp. He can now use the measurement tool to measure the length of the stretch of coastline. By clicking along the coastline next to the double green line the coordinates of each point where he clicked appear in the left hand window with 12 the length in kilometers. This shows that the stretch of beach is too short measuring just over two kilometers (Figure 7). Further panning now locates stretch of coastline further south which is of an appropriate length. Using the identify tool Mr Cloete can obtain more information about the section of beach he has chosen. This information appears in the left hand window and confirms that the section of beach is available for vehicle beach access (Figure 7). Mr. Cloete now decides to apply for a permit for this stretch of coastline as it will be ideal for collecting his kelp. Vehicle beach acces is allowed, it is long enough and there is easy access from nearby roads. Adding annotations to the map A set of annotation tools is available to draw on the map (line, rectangles and polygons) as well as adding text to the map. Mr. Cloete now marks the area of beach he wishes access to using the polygon tool and labels it using the text tool. He traces the along the road he will use for beach access using the line tool and labels it using the text tool. He places a point at his point of access using the point tool and labels it using the text tool. He saves his annotations on his map to the server using the save to server tool. 13 Figure 8 Web Map Services: annotating the map and saving changes to the server. The generated link may be saved in list of favourites or emailed. Sending an application for a beach access permit The save to server tool generates a link. There is an option to save the link to his list of favourite URL’s so he can access his work later as well as an option to email the link the link to somebody (Figure 8). Mr Cloete can now emails this link to the relevant authority [Northern Cape Conservation] along with his request for a permit (Figure 8). On receiving Mr Cloete’s application the manager opens the link. The Web Map Services arrages the scale, layers and annontations on the maps exactly as Mr. Cloete saved them. He can now see exactly which section of beach Mr. Cloete would like to drive along to collect his kelp as well as how he intends to access the beach. Mr. Cloetes request is granted as vehicle beach access is allowed along this section of coastline and there is an appropriate beach access route. It is clear from this example that this process allows the relevant government authority to make consistent and accurate decisions when granting permits. Time is also saved as sensible requests for permits are submitted by the public to areas where these are likely to be granted. 14 Management of information about illegal coastal cottages Since the first democratic election in South Africa in 1994 there has been a proliferation of illegal structures, mostly holiday cottages, along the section of the Eastern Cape coast know as the Wild Coast. This was formerly within the homeland area of the Transkei and had a separate administration. Various unscrupulous individuals used the hiatus caused by the change of government in the area to obtain false permission to build holiday cottages along the coast. The situation is further aggravated by the fact that most of these structures fall within a conservation area brought about by ministerial decree which proclaimed the entire coastline inland to one kilometer from the seashore a conservation area. As there are over 300 of these structures it has become problematic to maintain accurate information about the location, ownership and court proceeding details needed for the successful prosecution or suing of the structures’ oweners. To help with this problem a database has been developed within SACIC which captures sensitive information about each illegal structure, for example: i. Details about the owner and neighbours of the structure These include names, contact details, vehicle descriptions and registration numbers. As it is not always known who the owner of a structure is these details are maintained in a separate table in the database and linked to the table of illegal structures details. ii. Details of the illegal/legal structure These include amongst others details about the area where the structure is e.g. municipality and magisterial district, y and coordinates, photographs of the structure, links to the owners and neighbour details, aerial photography, environmental reports etc. The legal process information concerning the structure such as important uploaded documents and court proceeding details are also kept (Firgure 9). iii. An Web Map Services makes it possible for managers to locate the illegal structure on a map. All this information is password protected within a management system of SACIC. 15 Figure 9 A data capture/viewing screen of information about an illegal structure From a spatial point of view two aspects of this database are of importance. The first is that when new x and y coordinates are added to or changed in the database the Web Map Services is updated and the changes are immediately available to managers when viewing the cottage’s data on a map. The second is that the Web Map Services can be used to locate cottages along a stretch of coastline and retrieve their details. For example a manager may wish to retrieve all the information about any illegal structures with in a two kilometer radius of a structure located near Port St Johns (Figure 10). To accomplish this he chooses the radius identify tool. If he sets a two kilometer radius and selects the cottages layer in the appropriate dropdown box which appear in the left had frame once the tool is selected, all cottages within a two kilometer radius of where he clicks on the map will be listed in a pop up window. If he is logged into the system he will be able to retrieve the full details of each cottage by clicking on the link which accompanies each list cottage. As the system and be viewed and maintained remotely several managers can help to keep the database up to date and the information can be used the legal authorities for the information for successful prosecution and suing of the owners. 16 Figure 10 Web Map Services: using identify in radius tool to find illegal structure with a 2km radius. Conclusions These two proofs of concept illustrate how it has been possible to build on the experience which was gained with the delivery of a fairly simple Web Map Services in the initial phase of SACIC. It is now possible to build more complex decision support tools which can be used by managers and the public for more effective management of South Africa’s coastal resources. Such tools can be used by both managers and members of the general public, can be made to be open and accessible where appropriate and can be kept constantly up to date thus bringing South Africa a step closer in realizing the information goals set in Agenda 21. References Anon. 2000. White paper for sustainable coastal development in South Africa, our coast our future. Chief directorate Marine and Coastal Management. Department of Environmental Affairs and Tourism. http://www.internetworldstats.com/ 20 October 2005 Internet world stats usage and population statistics 17