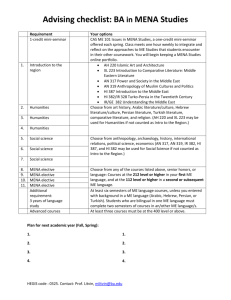

The Short-Term Dynamics of the Growth Equation

advertisement

DRAFT not to be quoted Reforms and Growth in MENA Countries : New Empirical Evidence by Mustapha Kamel Nabli World Bank, Washington, D. C. and Marie-Ange Veganzones-Varoudakis Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, CERDI, Clermont Ferrand (May 2002) 1 Introduction Despite apparent Reforms from the end of the 1980s and the beginning of the 1990s, the growth performance of the MENA region has often been disappointing. We show that this has been the case because MENA economies have most of the time lagged behind in terms of Reforms. Another explanation can be seen in the fact that the Growth dividend of some Reforms has been small or non existent. For this purpose we have generated aggregated Reform indicators using the Principal Component Analysis method which permits to aggregate basic indicators in a more rigorous way than a subjective scoring system. This methodology also avoids multicollinearity problems when estimating an equation including several disaggregated indicators. We have used panel data estimations techniques which allow some comparative analysis between the different regions of our sample, as well as between the MENA countries themselves. In addition to Economic Reforms, the link of Human capital and Physical infrastructure to Economic Growth has also been discussed. No studies have been undertaken ─ to our knowledge ─ in the area of Economic Policy and Economic Growth using the same methodology in the case of the MENA region. 2 This presentations is organised as follows: In the second section, we present the Principal Component Analysis of the Economic Reform, Human capital and Physical infrastructure indicators. Our analysis is based on a panel of 56 countries over the period 1970/80 (depending of the countries) to 19991. The third section discuss in a comparative perspective the progress in Economic Reform of the MENA economies and their development in Human capital and Core infrastructures. In the fourth section, we estimate a growth equation including the various composite indicators. The fifth section presents the impact of Economic Reforms, Human capital and Physical infrastructure on the growth performance of the MENA economies. We illustrate that some inappropriate policies had a strong negative influence on the growth performance of the region. The last section concludes. 1 Among these countries, 19 are African countries (8 CFA and 11 non CFA), 13 Latin American countries, 11 Asian countries and 12 MENA countries (of which 11 developing countries, see Annex 1 for the list of countries). 3 Economic Reform, Human Capital and Physical Infrastructures A-Macroeconomic Stability (MS): Inflation (p) and Public Deficit as a percentage of GDP (PubDef), (Fischer, 1993 ; De Gregorio, 1992); Foreign Exchange Parallel Market’s Premium [(lBmp, in log, Pinto, 1990] B-External Stability (ES): External Debt in percentage of GNI (DebExGni) and of exports (DebExX), Current Account in percentage of exports (CurAcX) C-Structural Reforms (SR): Trade Policy: (Balassa, 1978 ; Feder, 1982). - TradeP1 = X+M/GDP from which we have deducted the “Natural Trade Openness” (Frankel and Romer, 1999) and TradeP2 = TradeP1- X (oil + Mining) M3 to GDP [(M3) (Levine, 1997) D-Human capital (H): the Infant Mortality rate (lMort) as a proxy of the Health conditions of the population. the number of years of schooling of the population (lH1) for Primary, (lH2) Secondary and (lH3) Superior education. (Lucas, 1988, Psacharopoulos, 1988 ; Mankiw, Romer and Weil, 1992). E-Physical infrastructures (Phys): the density of the Road Network [lRoads in km per km2] the number of Telephone Lines per 1000 people [lTel ] (Barro, 1990 ; Aschauer, 1989 ; Murphy, Shleifer and Vishny, 1989). 4 Macroeconomic Reforms Most MENA countries undertook better Macroeconomic policies some starting in the 1980s (Morocco, Tunisia and Jordan essentially) and others in the 1990s after a decade of regression (Iran, Syria, Algeria, Egypt, Charts 1.1 and 1.2) Successes were achieved in containing Inflation, which is now particularly low in Morocco, Jordan and Tunisia (Chart 2.2, Annex 3). Improvements in reducing Public Deficit were made in Egypt, Jordan, Iran, Syria, Algeria (Chart 3.2, Annex 3). Black Market in Exchange Rate was ended in almost all the countries (Chart 4.2, Annex 3). However, Public Deficit still fluctuated between 1 to 3 % of GDP in the 1990s which is a bit high compared to other regions (Charts 3.1 and 3.2, Annex 3). In Egypt, less success was achieved in fighting Inflation, which is even higher in Algeria and Iran (above MENA, Asia and CFA Africa average, Charts 2.1 and 2.2, Annex 3). Black Market in Exchange Rate has not been controlled in Iran, Syria and Algeria, due to capital controls or political instability (Chart 4.2, Annex 3). 5 External Stability Reforms MENA countries achieved poorly during the whole period far behind Latin America and Asia (Chart 5.1). External Stability shows a clear deterioration in the 1980s. This result is largely explained by the unsustainable level of external Debt (Charts 6.1 and 7.1, Annex 4) due to the high level of public investment of the 1970s and 1980s (Annex 8). Even if in the 1990s sizeable efforts were made in re–negotiate the external Debt, its burden remains a problem in most MENA economies. In the 1990s, MENA countries’ external Debt accounts for 60-70% of GNI in Morocco, Egypt, Algeria, Tunisia (around 150 to 200% of exports) and more than 130% of GNI in Syria and Jordan (Charts 6.2 and 7.2, Annex 4). In the 1990s, Morocco and Egypt were the only two countries which have reduced their external Debt2. This situation indicates that a significant scope for debt reduction still exists in the region. However, MENA economies are among the best performers as far as Current Account balance is concerned (Chart 8.1, Annex 4) and efforts in reducing deficits are noticeable almost everywhere. 2 Morocco and Egypt did benefit from major debt forgiveness following the Gulf War in the early 1990s. 6 Structural Reforms MENA countries has performed rather well and only been surpassed by the Asian economies in the 1990s (Chart 9.1.A and 9.1.B., Annex 5). This result is largely due to the high financial depth of the MENA economies (M3 to GDP having averaged 60 to 80 % ). Financial depth has been particularly significant in Jordan and Egypt (more than 100% of GDP) but has improved in almost all MENA countries to reach 50-60 % of GDP (Chart 10.2, Annex 5 ). This result does not mean that the economies benefit from a strong Banking system or a developed Financial sector (Nabli, 2000). On the opposite, Trade openness (30 to 40% of GDP) has been by far inferior than in Asia (45 to 70% of GDP, Chart 11.1, Annex 5). This is the case despite progress in the 1990s, particularly with the exports’ diversification of the non oil producing countries (Chart 11.2, Annex 5). Trade openness is now rather high in Jordan and Tunisia (60% of GDP), these countries being (with Morocco) the most diversified of the region. It remains, however, weak in Iran, Syria and Algeria (around 30% of GDP in the 1990s) who have difficulties in moving from oil production and a State dominated management of their economies. 7 Human Capital Realisations of MENA countries have been rather satisfactory during the 1980s and the 1990s. Progress was, nevertheless, slightly better in Asia and Latin America (Chart 12.1). Mortality rates have been divided by 3 compared to the 1970s. Levels are now comparable to Asia and Latin America (Chart 13.1, Annex 6). Best performer has been Egypt, but noticeable efforts were also made by Iran, Algeria, Tunisia and Morocco (Chart 13.2, Annex 6). For Primary Education Tunisia exhibits the best results in the 1990s (5 years of Primary schooling) followed by Jordan, Algeria, Syria and Iran (around 4 years of schooling, Chart 14.2, Annex 6). In Secondary education, leaders have been Syria, Iran, Egypt, and Jordan (with 1.5 to 2 years of schooling). Progress in Algeria, Tunisia and Morocco have conversely been weaker (Chart 15.2, Annex 6). In Superior education, Syria, Jordan and Egypt (with 0.6 years of schooling) performed far better than Algeria, Tunisia, Morocco and Iran, whose level of Superior education remains low (around 0.1 years of schooling, Chart 16.2, Annex 6). 8 Core Infrastructures MENA countries indicators of Physical infrastructure are weak. (Chart 17.1). This assessment hides differences between countries (Chart 17.2) Performance of MENA countries in Road network are not better than in Africa (Charts 18.1 and 18.2, Annex 7). Even if a majority of countries have improved their level of Roads infrastructure, this level remains low in Jordan, Algeria and Egypt. Better progress has been made by Syria, Tunisia, Morocco and Iran, which level is close to that in Latin American but far from the Asian level. In spite of real progress in almost all MENA countries, the level of Telephone equipment of the region remains low compared to Latin America and Asia (Charts 19.1 and 19.2, Annex 7). Only Iran, Syria and Jordan reveal level of equipment similar to Latin America. However, this level still remain inferior to Asian countries. 9 Growth Performance in the MENA Countries MENA countries reveal a rather disappointing pattern in economic growth. This is the case despite some progress in various areas of Reforms. Even if the growth performance of the 1990s has improved in almost all MENA countries, GDP per capita growth rates have been largely surpassed by Asia (Chart 20.1). Syria and Tunisia have been the best performers of the group, followed by Egypt and Iran. Outcome are, however, poor in the case of Morocco whith a decreasing trend across the period, as well as Algeria affected by the fall in oil prices and the political turmoil (Chart 20.2). 10 Economic Reforms, Human Capital, Physical Infrastructure and Growth The long run Growth equation is based on Barro and Sala-I-Martin (1995)3 ln(y i,t) = c + a*ln(y i,t -1) + b*l.ln(Inv i,t) + d1* (MSi,t) + d2*(ESi,t) + d3 *(SRi,t)+ e1*(Physi,t) + e2.*(Hi,t) (1) with: - y i,t –1 = GDP per Capita of the previous period - Inv i,t = Investment ratio to GDP - MSi,, t = Macroeconomic Stability Indicator - ESi,,t = External Stability Indicator - SRi,,t = Structural Reform Indicator (SR1 and SR2)4 - Physi,,t = Physical Infrastructures Indicator - Hi,,t = Human Capital Indicator - c = intercept, a, b, d1 to d3, e1 to e2, = parameters, t = time index and t = error term. 3 The short-run dynamic of the REER has also been estimated through an error correction model (Equation (A3-1) in Annex 10) 4 (SR1) is based on the first Trade Policy indicator (TradeP1) and (SR2) on the second one (TradeP2) 11 Table 2: Estimation Results of the Long Term Growth Equations Dependent Variable ln(yt) Independent Variables ln(yt-1 ) In(invt) MSt ESt SRt Physt Ht Adjusted R² Fischer test Haussmann test Eq1 -0.15 (7.93) 0.07 (5.90) 0.009 (1.81) 0.03 (5.71) -0.0008a (0.10) 0.02 (1.05) 0.02 (1.72) 0.26 3.6 44.7 Eq2 -0.11 (6.14) 0.011 (1.96) 0.03 (5. 10) 0.014a (1.64) 0.02 (1.18) 0.0003 (0.03) 0.19 2.79 37.5 Eq3 -0.15 (7.87) 0.08 (6.70) 0.009 (1.76) 0.03 (5.51) -0.002b (0.32) 0.02 (1.00) 0.03 (2.03) 0.28 3.5 49.9 Eq4 -0.10 (5.26) 0.01 (1.92) 0.023 (4.56) -0.007b (0.98) 0.02 (0.97) 0.004 (0.30) 0.26 3.6 44.7 Note: Student t statistics are within brackets. The number of observations used in the regression is respectively 648 and 578. Data have been compiled from WDI, GDF, GDN and LDB World Bank databases. Coefficient in bold are significant at 1%, 5% or 10 % level. a: SR1 (including TradeP1) and b: SR2 (including TradeP2) Estimated relationships are consistent with the theory. An increase in Investment, Human capital, Macroeconomic and External Stability leads to higher Growth rates. Estimations do not validate the role of Structural Reforms in improving the growth performance of the economies. They do not confirm neither the role of Physical infrastructure 12 Impact of Economic Reform, Human Capital and Physical Infrastructure on Growth of MENA Countries Calculation is based on the estimated elasticity of the aggregate indicators, as well as on the weights of each Principal Component in the aggregate indicator combined with the loadings of the initial variables in each Principal Component. Table 3 : Economic Policy and Infrastructure Variables Short and Long Term Coefficients/Elasticities (Equation (1): Index Variables Short Term Elasticities Long Term Standardized Level Elasticities Variables Variables -0.004 -0.001 -0.008 -0.002 -0.002 -0.014 0.001 0.014 0.09 MS P ln(Bmp) PubDef ES DebExX DebExGni CurAccX -0.015 -0.012 0.011 -0.006 -0.029 0.021 -0.04 -0.19 0.14 SR* TradeP* M3* -0.0005 -0.0005 -0.001 -0.002 -0.007 -0.013 0.012 0.012 0.01 0.01 0.07 0.05 -0.013 0.013 0.015 0.014 -0.017 0.023 0.013 0.009 -0.11 0.15 0.09 0.06 Phys* ln(Roads)* ln(Tel)* H ln(Mort) ln(H1) ln(H2) ln(H3) * These variables are non significant 13 Table 4:Contribution of Human Capital to growth Years H Education Mortality Tot contribution GDP per Capita Primary Secondary Superior per 1000 of H Growth rate number of years of schooling pop Improvment Actual 3.6 5.5 7.7 -3.9 1980-89 Annual -0.7 2.9 6.3 7.4 -3.7 1990-99 Growth Rate 1.8 Without LT Elasticity 0.15 0.09 0.06 -0.11 Progress in H 0.5 0.5 0.5 0.4 1980-89 Contribution 1.9 -2.6 0.4 0.6 0.4 0.4 1990-99 to Growth 1.8 0 Human capital presents a strong effect on growth (table 3). Primary education shows a greater impact than Secondary and Superior education (Table 3). Improving Health conditions turns out to have a stronger impact than Secondary education (Table 3). Knowing that MENA region have developed a satisfactory level of Primary, Secondary education and Health conditions, Human capital has constituted a clear engine of growth (Table 4) . Improvement in Primary schooling has contributed to an average per year of 0.5 points of GDP per capita growth rate in the 1980s and of 0.4 during the 1990s. The same conclusions can be drawn for Secondary and Superior education (0.5 in the 1980s and of 0.6 and 0.4 respectively in the 1990s) Amelioration of the Health conditions has contributed to 0.4 point of growth for each period Globally, improvement in Human capital explains 1.9 points of growth for both period. This means that, without progress in Human capital, GDP per capita growth rate would have been of –2.6% in the 1980s (instead of –0.7%) and of 0% in the 1990s (instead of 1.8%, Table 4). 14 Table 5:Contribution of External Instability to growth Years ES DebX DebGNI CurAcc % Exports % GNI % Exports 15.4 3.0 0.7 1980-89 Annual -7.3 1.1 -1.4 1990-99 Growth Rate LT Elasticity 1980-89 Contribution 1990-99 to Growth -0.04 -0.6 0.3 -0.19 -0.6 -0.2 0.14 0.10 -0.20 Tot contribution of External Instability -1.1 -0.1 GDP per Capita Growth rate Actual -0.7 1.8 Without External Instability 0.4 1.9 In the 1980s External Instability had an important negative impact on growth. The increase in the Debt ratios led to the deterioration of 1.2 points of the GDP per capita growth rate (0.6 for each ratio, Table 5). On average, External Instability have cost yearly 1.1 points of GDP per capita growth rate in the 1980s and 0.1 in the 1990s. Growth could have reach of 0.4% on average per year (instead of 0.7%) in the 1980s and 1.9% (instead of 1.8%) in the 1990s. These results illustrate also the efforts made in the 1990s by most of the countries of the region in reducing their external fragility. 15 Table 6:Contribution of Macroeconomic Instability to growth Years MS 1980-89 Annual 1990-99 Growth Rate p % 9.00 -5.79 LT Elasticity -0.008 1980-89 Contribution -0.07 0.05 1990-99 to Growth bmp pubdef Tot contribution GDP per Capita of Economic Growth rate Actual level % GDP Instability 14.70 -0.08 -0.7 3.00 -0.02 1.8 Without External -0.014 -0.09 Instability -0.2 -0.01 -0.3 -0.4 -0.04 0.00 -0.04 1.8 Macroeconomic Stabilisation exhibits a much lower impact on growth. The only variable that seems to have substantially contributed to the absence of growth in the 1980s is the distortions in Exchange Rate . Augmentation of this variable has cost on average yearly 0.2 points of GDP per capita growth rate (Table 6). This makes of the Exchange Rate a non negligible factor in accompanying Economic Reforms. Overall, estimations fail to show a strong impact of Stabilisation of the economies Macroeconomic distortions have only cost on average yearly 0.3 points of GDP per capita growth rate in the 1980s. This means that growth performance of the region could have been of –0.4% per year (instead of -0.7%). 16 Conclusion Most MENA countries undertook better Macroeconomic policies starting in the 1980s (Morocco, Tunisia and Jordan essentially) or in the 1990s after a decade of regression (Iran, Syria, Algeria, Egypt) Performance in Structural Reforms seem also, at a first glance, satisfactory. This is, however, due to a high financial depth. On the opposite, Trade openness has been more deficient. MENA economies achieved also poorly in External Stability. This is largely explained by the unsustainable level of external Debt due to the high level of public investment of the 1970s and 1980s. Realisations of MENA countries in Human capital have been rather good. On the opposite Physical infrastructure has been weak. Our estimations show that Investment, Human capital, Macroeconomic and External Stability have led to higher Growth. They do not validate, however, the role of Structural Reforms and of Physical infrastructure. Human capital has presented a strong effect on Growth (1.9 points yearly of GDP per capita growth rate in the 1980s and the 1990s). External Instability has cost, on the contrary, 1.1 points of Growth yearly in the 1980s. This emphasises the importance to reduce MENA external fragility. Macroeconomic Stability exhibits a low impact on Growth, except for the distortions in Exchange Rate which appear to be a non negligible factor in accompanying Economic Reforms. 17 Annex 1 List of countries of the sample MENA AFRI CA CFA United Arab Emirates(ARE) Bahrain (BHR) Algeria (DZA) Egypt, Arab Rep. (EGY) Iran, Islamic Rep.(IRN) Burkina Faso (BFA) Cote d'Ivoire (CIV) Gabon (GAB) Cameroon (CMR) Gambia, The (GMB) Jordan (JOR) Kuwait (KWT) Malta (MLT) Morocco (MAR) Syrian Arab Republic (SYR) Tunisia (TUN) Niger (NER) Senegal (SEN) Togo (TGO) ASIA LATIN AMERICA NonCFA Botswana (BWA) Ghana (GHA) Kenya (KEN) Madagascar (MDG) Mozambique (MOZ) Mauritius (MUS) Malawi (MWI) Nigeria (NGA) Tanzania (TZA) South Africa (ZAF) Zambia (ZMB) Other Countries Israel (ISR) 18 Bangladesh (BGD) China (CHN) Indonesia (IDN) India (IND) Korea, Rep.(KOR) Argentina (ARG) Bolivia (BOL) Brazil (BRA) Chile (CHL) Colombia (COL) Sri Lanka (LKA) Malaysia (MYS) Pakistan (PAK) Philippines (PHL) Singapore (SGP) Thailand (THA) Costa Rica (CRI) Ecuador (ECU) Guatemala (GTM) Mexico (MEX) Peru (PER) Paraguay (PRY) Uruguay (URY) Venezuela, RB (VEN) Annex 2 : Principal Component Analysis Table A2.1 : Macroeconomic Stability Variables Component Eigenvalue Cumulative R2 P1 P2 P3 1.19 0.96 0.85 Loadings P lBmp PubDef P1 0.48 0.72 -0.67 0.40 0.72 1 P2 0.86 -0.16 0.45 P3 0.19 -0.68 -0.60 MS = 0.39/ 0.71*P1 + (0.71-0.39)/ 0.71*P2 ********************************************************************** Table A2.2: External Stability Variables Component Eigenvalue Cumulative R2 P1 1.83 0.60 P2 0.81 0.87 P3 0.362 1 Loadings DebExX DebExGni CurAccX P1 0.89 0.74 -0.69 P2 0.03 0.58 0.67 P3 0.45 -0.31 0.24 ES = P1 19 Table A2.3: Structural Reform Variables Component Eigenvalue Cumulative R2 P1 1.36 0.68 P2 0.63 1 Loadings TradeP1 M3 P1 P2 0.82 0.56 0.82 -0.56 SR = P1 Table A2.4: Human Capital Variables Component Eigenvalue Cumulative R2 P1 2.95 0.73 P2 0.50 0.86 P3 0.34 0.95 P4 0.19 1 Loadings ln(Mort) ln(H1) ln(H2) ln(H3) P1 0.79 -0.84 -0.91 -0.89 P2 0.58 0.33 -0.004 0.20 P3 0.15 -0.42 0.25 0.27 P4 0.08 0.03 0.32 -0.29 H = P1 ********************************************************************** Table A2.5: Physical Infrastructure Variables Component Eigenvalue Cumulative R2 P1 P2 1.41 0.58 0.70 1 Loadings ln(Roads) ln(Tel) P1 P2 0.84 0.53 0.84 -0.53 Phys = P1 20 Annex 3: Macroeconomic Stability Indicators 21 Annex 4: External Stability Indicators 22 Annex 5 : Structural Reform Indicators 23 Annex 5 : Structural Reform Indicators (end) 24 Annex 6: Human Capital Indicators 25 Annex 6(end) 26 Annex 7 : Physical Infrastructure Indicators 27 Annex 9 Table A-5: Augmented Dickey Fuller Test (ADF) Equations (1) Variable ln(y) ln(Inv) MS P lBmp PubDef ADF statistic k(1) Trend -1.89 1 yes -1.92 1 no Critical value(2) -1.82* -1.82* ADF test I(0) I(0) -2.76 1 no -1.82* I(0) -2.43 1 no -1.82* I(0) ES DebExX DebExGni CurAccX -1.06 -2.47 5.12 1 1 1 no no no -1.69*** -1.82* -1.69*** I(1) I(0) I(1) SR TradeP M3 -3.77 -2.90 1 1 no no -1.82* -1.82* I(0) I(0) H ln(Mort) ln(H1) ln(H2) ln(H3) - 3.3 - 1.83 - 2.05 -1.93 1 1 1 1 no no no no -1.82* -1.82* -1.82* -1.82* I(0) I(0) I(0) I(0) Phys ln(Roads) ln(Tel) -3.65 -2.76 1 1 no no -1.82* -1.82* I(0) I(0) -1.82 3 no -1.82* I(0) Residual of the Estimation (1) k is the number of lags in the ADF test. (2) Im, Pesaran and Shin (1997) critical values (respectively * 1%, ** 5% and *** 10% level). Data have been compiled from WDI, GDF, GDN and LDB World Bank databases. 28 Annex 10 The Short-Term Dynamics of the Growth Equation The short-term dynamic adjustment of the GDP per capita toward its equilibrium level has been estimated through an error correction model: ln(y i,t) = - a ln(y i,t -1) - ln(y i,t- 1 ) + a’ ln(y i,t -1 ) + b1.ln(Inv i,t) + b2.(SRi,t) + b3.(MSi,t) + b4.(ESi,t) + b5.(Physi,t) + b6.(Hi,t) + c1.ln(Inv i,t -1) + c2.(SRi,t -1) + c3.(MSi,t -1)+c4.(ESi,t -1) +c5.(Physi,t -1) + c6.(Hi,t -1) (A4-1) Table A-6 : Estimates of the Error Correction Model Dependent variable: ln(yt) Variable 1t-1* ln(y i, t-1 ) ln(Inv i, t) (SR i, t ) (MS i, t) (ES i, t) (Phys i, t) (Hi, t) ln(Inv i, t-1) (SR i, t-1) (MS i, t-1) (ES i, t-1) (Physi, t-1) (Hi, t-1) D-W Elasticity -1.00 -0.83 0.04 -0.01 -0.001 -0.006 0.013 -0.003 -0.04 -0.013 0.005 0.006 0.002 -0.006 2.20 Student (6.57) (6.49) (2.05) (1.5) (0.18) (0.94) (0.31) (0.12) (1.74) (0.42) (1.31) (0.99) (0.01) (0.2) Note: Student t statistics are within brackets. The sample includes 176 observations over 1969/80 -1999 period. * 1t-1 is the lagged error term of the cointegrating Equations (1). Data have been compiled from WDI, GDF, GDN and LDB World Bank databases. 29