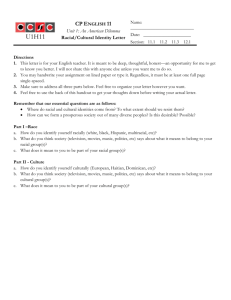

History and Politics in the Development

advertisement