The Garden of Forking Paths: Fiction, Reality

advertisement

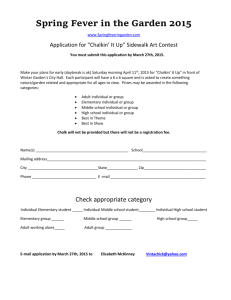

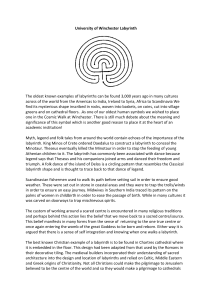

1 Deep and Distant Ethics: The Fictional Approach in Chinese Gardens and Urbanism Hui Zou Abstract This paper begins by analyzing Jorge Luis Borges’s fictional creation “The Garden of Forking Paths” while searching for architectural realities in his novel. It then progresses to a discussion on the eighteenth-century Chinese imperial Garden of Round Brightness to demonstrate the fiction-reality relationship in the mystic garden existence. With the revealed historical context, this research interprets the Daoist sage Laozi’s concept, “the deep and distant ethics” (xuan-de), by introducing the metaphoric approach of architectural fiction, which acts as a poetic resistance for ethical architecture in Chinese urbanism. Garden of Forking Paths In the 1940s, the Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges wrote a fictional novel entitled “The Garden of Forking Paths.” Although there have been many synopses of this story in secondary sources, I will present one from a different perspective. This interpretation focuses on the architecture reality superimposed with the fictional narrative. Borges’s book begins with a historical record of the First World War regarding a British attack against German-occupied France that was delayed a few days. The delay was related to a Chinese national, Yu Tsun, a former English professor at a German school in Qingdao, eastern China. Tsun worked as a spy for Germany during his stay in Britain. He was being chased 2 by a detective while attempting to find a way to report on a secret artillery location. In a phone book, Tsun found the name Albert, who was a stranger living in the village of Ashgrove. Arriving at this village, Tsun was told that if he took the road to the left and turned again to his left at every crossroad, he would find Albert’s house. Walking down the solitary road under the full moon, he recalled that continuously turning to the left was a common procedure for discovering the central point of certain labyrinths. Tsun grew up in his father’s symmetrical garden. His grandfather, the former governor of Yunnan Province, renounced worldly power and dedicated himself to writing a novel and constructing a labyrinth for thirteen years until he was murdered by a stranger, leaving the novel incoherent with only chaotic manuscripts left behind and the labyrinth lost. As Tsun continued to hurry along the winding country road and reminiscing on his grandfather’s lost labyrinth, he imagined an infinite labyrinth that would encompass the past as well as the future while involving the cosmos. By coincidence, Albert served as a missionary in the Chinese city of Tianjing and later used this experience to become a sinologist. As he greeted Tsun, they walked through the zigzagging path of the front garden and entered the library while talking about Tsun’s grandfather. According to Albert’s research, Tsun’s grandfather isolated himself in the Pavilion of Limpid Solitude, located at the center of an intricate garden, to work on his book and the labyrinth. Albert then showed the guest a minimum ivory labyrinth, which, he thought, was the lost labyrinth made by Tsun’s grandfather. Tsun was also shown a letter in which his grandfather described his project as “a garden of forking paths.” In Albert’s view, the “garden of forking paths” symbolized an invisible labyrinth of infinite time in which all possible outcomes occurred. As Tsun had planned, he murdered Albert and was later arrested. The murder was covered in a local newspaper and thus, those in Germany received 3 a secret message from Tsun that the new British artillery park was located in the city called Albert. Borges used the labyrinth as the primary structure of the plot, with multiple labyrinths at both the physical and metaphysical levels: Physical Labyrinths Metaphysical Labyrinths 1. Geographical labyrinth 1. Historical book of WW I 2. Village of Ashgrove 2. Phone book 3. Albert’s house 3. Grandfather’s letter 4. Albert’s library 4. Albert’s collection of books 5. Grandfather’s minimum labyrinth 5. Grandfather’s novel 6. Grandfather’s intricate garden 6. Grandfather’s classic books 7. Grandfather’s Pavilion of Limpid Solitude 7. The novel Dream of Red Chambers 8. Father’s symmetrical garden 8. Newspaper report of Tsun’s death Table 1 The physical and metaphysical labyrinths in Jorge Luis Borges’s “The Garden of Forking Paths” The first physical labyrinth was on the global geographical scale. Tsun came from Qingdao, a German colonial city on the eastern coast of China. His grandfather was the former governor of Yunnan, a remote province in southwestern China. Albert, the sinologist, was a former missionary in Tianjing, which was further north of Qingdao. The site of the encounter between the two strangers was in Britain, a Western empire that was a far distance from China. The second physical labyrinth was the village of Ashgrove, where a zigzagging country road led Tsun towards the center of the village—Albert’s house. The third was the front garden of Albert’s house. The fourth was the household library where Eastern and Western books were stored and the encounter between the two strangers took place. The 4 fifth was Tsun’s grandfather’s minimum labyrinth which was stored in the library. This labyrinth led to the sixth one, Tsun’s grandfather’s garden in remote China, and the seventh one, the Pavilion of Limpid Solitude within that garden. The eighth physical labyrinth, the least described by Borges, was the garden of Tsun’s deceased father, which was the foreshadowing of Tsun’s death. Paralleled with the physical labyrinths, metaphysical labyrinths were presented as books and other types of writings. The first metaphysical labyrinth was the historical book that recorded the spy incident. The second was the phone book where Tsun found the name of Albert. The third was Tsun’s grandfather’s letter. When Albert tried to show this letter to Tsun, he was murdered and the detective dashed through the front garden to arrest Tsun. The fourth metaphysical labyrinth was Albert’s collection of Eastern and Western books. The fifth was the chaotic novel written by Tsun’s grandfather. The sixth was the classic books, which Tsun’s grandfather, a scholar official, tirelessly interpreted. The seventh metaphysical labyrinth was the famous novel Dream of Red Chambers of the Qing dynasty, whose amorous narrative took place in the Garden of Grand View. The eighth was the newspaper reports of the Albert’s murder and ultimate punishment of Tsun. If judged independently, each physical and metaphysical labyrinth had the potential to be an authentic historical fragment. Within each pairing of physical and metaphysical labyrinths, the metaphoric connection was convincing. The third and fourth pairs hinted that the cultural encounter itself was a labyrinth. The metaphoric connections in the sixth and seventh pairs demonstrate Borges’s deep knowledge of the Chinese culture. The most hidden connection was in the eighth pair where Tsun’s deceased father’s symmetrical garden, which was associated with Tsun’s act of murder through the sense of death. When these 5 labyrinth fragments, the “illusory images” described by Borges, were interwoven into a narrative, the fictional novel was constructed. Because each fragment was precisely located in a specific historical and cultural context, the fiction presented itself as a reality. If as stated in the fifth pair of labyrinths that “the book and the labyrinth were one and the same,”1 the fictional text should be understood as a labyrinth (Figure 1). Thus, the fiction and reality became one in the primary labyrinth which Borges called the “labyrinth of labyrinths” or the “infinite labyrinth” where one path of time could lead to others and they sometimes converged, just as in the story where Tsun sat beneath the English trees and reminisced on the lost labyrinth of his grandfather. The infinite labyrinth defines a crosscultural order where physicality remains permanent, which is most likely why Borges did not differentiate the physical details between English gardens and Chinese gardens, but rather emphasized their commonality through the symbol of the labyrinth. Figure 1 An architectural installation work, “A Book of Gardens,” by Hui Zou, 2007 6 Garden of Round Brightness As Borges’s narrative demonstrates, the mystic order of the infinite labyrinth is neither completely controlled nor fully revealed. The mystic order was not of space, but that of time, which confined the historicity of the infinite labyrinth. It is also interesting to note that the name of the infinite labyrinth was “The Garden of Forking Paths,” which implied the physicality of both English and Chinese gardens. Borges’s fictional labyrinth creates a situation where the reader begins to question if a built environment can be experienced as fiction. One of Borges’s metaphysical labyrinths was the Chinese classic novel Dream of Red Chambers, whose narrative was based on the fictional Garden of Grand View. There are two reasons for relating this fictional aristocratic garden with the contemporaneous imperial Garden of Round Brightness. First, the novel was written at the foot of the Fragrant Hill in the northwestern suburb of Beijing where the Garden of Round Brightness was located. Second, the fictional garden shares the same title, Grand View, with a panoramic painting of the realistic garden. During the 1750s, exactly when the novel Dream of Red Chambers was being written, a group of Western Jesuits built a European garden for the Chinese emperor in the most remote corner within the Garden of Round Brightness. The Chinese garden was composed of the Forty Scenes, which were organized into a numeric sequence (Figure 2). The emperor gave a poetic name and wrote a poem for each scene, which was also recorded through a painting created by the court painters. As expressed in its poetic name and poem, each named scene was a passionate encounter between the emperor’s historical mind and the specific garden view. The multiple named scenes created a sort of path, which appeared mystic and confusing. If connecting the spots of the neighboring two scenes with a straight line, a 7 diagram of the zigzagging path, like a constellation pattern in the sky, comes to light. Although the garden was experienced as a labyrinth, in this diagram, surprisingly, there is neither an overlap of the lines nor a center. The hidden cosmic order defined the emperor’s poetic journey towards infinity. Figure 2 The hidden labyrinth path of the Forty Scenes in the imperial Garden of Round Brightness (1740s), Beijing, drawn by Hui Zou In contrast to the winding paths of the Chinese garden, the Jesuit garden was laid out on a T-square plan with two major axes. The garden view was composed of multiple exotic scenes, such as the Western multistoried buildings, mechanical fountains, geometrical pools and a geometrical hill. In a set of twenty copperplates committed by the emperor, the garden scenes were all depicted through the Western technique of central perspective. On the northern end of the first axis, there was a Western labyrinth whose center was occupied 8 by an imperial throne (Figure 3); on the eastern end of the second axis stood an illusionary stage set of an open-air theater. According to the imperial records, the garden usually served as a secret viewing place after the emperor toured among the Forty Scenes. While this secret garden extended the emperor’s poetic journey into opacity, the Western labyrinth and theater within the garden led his imagination further into infinity. Figure 3 The copperplate of a Western labyrinth in the European garden “Western Multistoried Buildings” (1750s) within the Garden of Round Brightness, drawn by Yi Lantai, 1786 According to the emperor Yongzheng’s garden record, the concept of Round Brightness indicated a “deep and distant” virtue, which was difficult to understand.2 His approach of interpreting the meaning of the garden was referring to ancient books, meanwhile identifying the “virtue of Round Brightness” through his garden experience. The virtue of Round Brightness reflects the Daoist sage Laozi’s concept of “deep and distant ethics,” which can reach the ultimate harmony by “acting opposite of the regular way,”3 like the detour in garden labyrinths. It is this paradoxical movement of detouring that unified Jesuit perspective view and the emperor’s discursive mind. 9 Two Cultural Plazas The Garden of Round Brightness demonstrated how the paths of varied historical times and cultures forked and converged within a garden reality where the named garden scenes acted as metaphoric images. The surrealist André Breton called the assemblage of metaphoric images as the “poetic analogy” which acted as the bridge between two objects of thought situated on different planes.4 Dalibor Vesely referred the theory of poetic analogy to the art of collage in which two distant realities met by chance. He analyzed how the architectural collage of environmental metaphors can be open to a series of readings and reveal the situational character of dwelling in an overlapping context.5 This poetic analogy is hard to realize in today’s Chinese urbanism, which advocates a technical worldview of realism. The homogenous urban landscapes that make up the reality of modernization fail in creating the fictional context for ecstatic cultural encounters. Nevertheless, at the beginning of this new urbanism in the 1980s, Borges’s works were seriously studied by the younger architectural faculty and their students in a remote city of southwestern China.6 One member from this group, Tang Hua, won a design award in Japan in 1986 with a fictional project, a neighborhood cultural plaza. A decade later, he designed another cultural plaza project that was built in Shenzhen, a coastal city in southern China. In the 1986 project, Tang Hua used the broken bridge as a metaphor, implying his design as a “metaphysical bridge” (Figure 4).7 He constructed an architectural fiction of a labyrinth, which was composed of mnemonic fragments such as the clock tower in an old town, the 10 stories circulating in a pebbled plaza under moonlight, and a long stone bridge leading towards a distant place where you feel as if you have been before. The center of this labyrinth is occupied by a solitary man, the dreamer. The clock tower looks exotic in the Chinese tradition, but its image in silence, as in De Chirico’s paintings, brings about the sense of time. Both the bridge and the clock tower create a path towards the mystical world. The composition of the design drawing evokes the paradigmatic memory of the Chinese poetic landscape of water, mountains, a pagoda and a stone arched bridge. Figure 4 The Cultural Plaza of a Community of Tiled-roof Houses, designed by Tang Hua, 1986 Tang Hua’s dedication to constructing architectural fictions was not held up by the prevalent pragmatic practice in Chinese urbanism. To the contrary, he developed his solitary revelry into a new understanding of urbanity through architectural practice. In the Nanyou Cultural Plaza in Shenzhen (Figure 5), built in 1994, the geometrical elements and architectural forms originating from different cultures were used as metaphoric images, such as the horizontal 11 circle, vertical clock tower, shadowed colonnades, gateways, zigzagging corridors and long stairways. These mnemonic images were assembled with a geometrical play of fusion and contrast, which implied the movement of the Daoist diagram of taiji, the ultimate harmony.8 The plaza, working as an open-air theater, is also the entrance of an interior theater. The theatricality of the building, incorporating the sky and the distant mountain landscapes, provides an evocative stage for urban life. Figure 5 The final model of the Nanyou Cultural Palza, Shenzhen, China, designed by Tang Hua, 1994 As an architectural intellectual, Tang Hua observed the paradox between the increasing accumulation of wealth in modern civilization and the loss of our spiritual home. In his designs, he explored the possibility that spirituality could be retrieved through composing a mythical architectural text. On the built cultural plaza, he wrote, “This design presents an unnamable mystic tone. Its morphology acts as a metaphor of the cosmos while reflecting the historical sentiment narrated by mythologies and sayings. When these aspects are 12 embodied in architecture, the human existence and the absent divinity begin to be revealed between the earth and the sky” (Figure 6).9 Ten years later, the plaza is now surrounded by homogeneous high-rise buildings and is often covered with kitschy commercial advertisements. However, as he explored in the fictional cultural plaza two decades ago, this built cultural plaza remains as a “primary gate” for citizens to enter into a spiritual dream. Figure 6 The built Nanyou Cultural Plaza, Shenzhen, China, 1996, designed by Tang Hua Observing the unavoidable standardization of housing in the universal way of living, the philosopher Paul Ricoeur points out the conflict between the universal civilization, which is based on the technical worldview, and the national culture, which depends upon “the ethical and mythical nucleus of mankind.” He describes this mythical nucleus as “the awakened dream of a historical group.”10 Through reading Borges and other translations in the early 1980s, Tang Hua and his colleagues acted as a historical group in Ricoeur’s sense. They attempted both the mythical and mystic dimensions of human existence, which led them to explore the poetic truth of architecture. It is the ability to keep the dream awakened that continues to be a challenge to Chinese architects. Conclusion 13 In the infinite labyrinth, there exists the constantly repeated movement of forking and converging that does not lead to a final goal. The activity of walking through confusing paths is itself the intention of the labyrinth. In both the fictional labyrinth and the garden as a labyrinth, there is something that asks to be understood in what it intends. This meaning does not simply lie in what we immediately see and read, but rather, it rests upon an intricate interplay of showing and concealing. The labyrinth requires us to learn how to perceive the labyrinth as it is and how to rise above the universal leveling process in which we cease to notice anything. Such a poetic resistance, acting opposite of the regular way, will lead to Daoist “deep and distant ethics,” the ultimate harmony. This ethical destination approached through poetical resistance compels a necessity of an architectural pedagogy that seeks to evoke imagination through reading to open up another dimension of reality, the fiction. 14 Notes Jorge Luis Borges, “The Garden of Forking Paths,” Labyrinths: Selected Stories and Other Writings, ed. Donald A. Yates & James E. Irby (New York: A New Directions Book, 1964), 25. 2 See the punctuated version of Yongzheng’s record of the Garden of Round Brightness, “Shizong xianhuangdi yuzhi Yuanmingyuan ji,” in Yuanmingyuan: xueshu lunwen ji, ed. Zhongguo yuanmingyuan xuehui 4 (1986): 102. 3 See the concept of xuan-de in chapter sixty-five of Laozi (4th century BC), in Zhou Shengchun anno., Baihua Laozi (Xi’an: Sanqin chubanshe, 1994), 108. 4 See André Breton, “Ascendant Sign,” in Mary Ann Caws ed., Surrealist Painters and Poets: An Anthology (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press), 135. 5 Dalibor Vesely, Architecture in the Age of Divided Representation: The Question of Creativity in the Shadow of Production (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2004), 344. 6 This loosely organized group was active during the 1980s at the School of Architecture, Chongqing Institute of Architecture & Engineering, in southwestern China. 7 Tang Hua, “Wawuding juzhu xiaoqu huodong zhongxin [The cultural center of a community of tiled-roof houses],” Shijie jianzhu, n. 2 (1987): 58. I thank the architects in Shenzhen, including Tang Hua, Liang Ting and Yin Yanming, and Dr. Wang Fangji of Tongji University for providing the photo images of Tang Hua’s designs. 8 The taiji diagram, a circle containing the interpenetrative forces of yin and yang, was created by Zhou Dunyi, a Neo-Confucianist philosopher of the Northern Song dynasty (11 th century). 9 Tang Hua, “Guji: Shenzhen Nanyou wenhua guangchang shiyi [Solitude and tranquility: the design of the Shenzhen Nanyou cultural plaza],” Jianzhushi 68.2 (1996): 96. The quote is translated by Hui Zou. 10 Paul Ricoeur, “Civilization and National Cultures,” History and Truth, trans. and intro. by Charles A. Kelbley (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1965), 274-76, 280. 1