Mary Rowlandson and the Captivity Narrative

advertisement

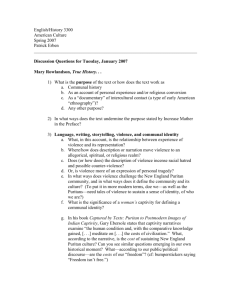

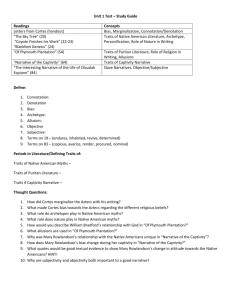

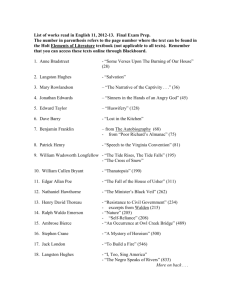

Rowlandson Lecture (F05Rowl Lec Notes), p. 1 Mary Rowlandson and the Captivity Narrative A. Time Line and Brief Biography 1637 (1635?)--Mary White born in Somerset county, England 1639--family moves to Wenham, Mass. 1653--family moves to Lancaster [map from NS] 1656--Mary White marries Joseph Rowlandson 1662--More than 50,000 British in New England 1675--John Sassamon murdered (Jan.)(Christian Massachusett Indian, attended Harvard, aide to Metacom, told English about coming rebellion) murdered 3 Wampanoags convicted and hanged (June 8) Wampanoags attack Swansea under general leadership of Metacom (King Phillip)(June 24) 1676--Feb. 10: 400 Indians attack Lancaster and capture Mary Rowlandson [map] Sold into slavery to Narrangansett sachem Quinnapin (Quanopin) and his three wives, including the "squaw sachem" of Pacosset Wampanoags, Weetamoo (Wettimore) May 2: Rowlandson released from captivity May: Metacom's wife and nine-year old child captured by British and sold into slavery in Bermuda August: Metacom killed, rebellion ends 1677--Rowlandson's move to Wethersfield, Connecticut 1678--Joseph Rowlandson dies 1679--Mary marries Samuel Talcott 1682--Rowlandson's narrative published 1691--Samuel Talcott dies 1711--Mary (Rowlandson) Talcott dies II. Metacom's War (King Phillip's War) [image of Metacom] A. Bloodiest War in American History: 5,000 Indians killed, 40% of the Indian population in that area; 2,500 Colonists killed, 5% of the British population. B. Tensions Over Land (see John Easton, "A Relacion of the Indyan Warre" [1675], pp. 115-118) 1. As in Lear, the conflicts begin over the distribution of land. The Indians had sold land to the Puritans, but as the Puritan communities expanded, and pushed further west, the Indians realized that they were in danger of losing the entire area. 2. Indians said English cheated them through English arbitrators in land disputes (116) and accepting written evidence of agreements (117) 3. Results: a. Border disputes erupted between Indian and Puritan towns and farmfields. Rowlandson Lecture (F05Rowl Lec Notes), p. 2 b. Dissension among the Indians who blamed other Indian towns for giving up too much, and blamed their leaders for making bad deals. C. Two Interpretations 1. God's punishment of his people: [text] a. E.g. Samuel Groome's sermon just after the outbreak of King Phillip's War: he attacked the New Englanders for "quarrels which you have brought upon yourselves, through your pride and unequal dealing with dissenters in matters of religion, and by your treacherous practices toward the Indians, all which crieth very loud for vengeance. . . . since ye fled out of Old england into the Wilderness of Neew England . . . have not brought forth many monstrous births, like bruit beasts, like dragons, like cockatrices, like roaring lyons and Devouring Wolves?" (A Glass for the People of New England in Which They May see themselves [London 1676] q'ed in Bauer 670) Afflictions are signs of both punishment and election, hence the double message of the jeremiad: you are God's people, and you are in danger of losing that status because of your sins. b. E.g.: Joseph Rowlandson's sermon c. E.g.: Rowlandson: 105-06 2. Satan's war against God's people: Apocalyptic struggle of good vs. evil E.g. Rowlandson: demonizes Indians:[image of Indians as devils] Read: devils and heathens: 69-71 "O" 3. Association and Dissociation The two interpretations are compatible because if Satan is really acting on God's orders, as he always is, then his attack is really God punishing his people indirectly through Satan. However, their implications for notions of community are very different: a. Punishment implies disruption If God punished for backsliding, that indicates disruption and difference within the community as some people fall away from the right path b. Attack create unity If Satan attacks, the threat comes from the outside and is directed against a community that is actually unified by that threat. III. The Cultural Work of the Captivity Narrative Rowlandson Lecture (F05Rowl Lec Notes), p. 3 A. "the starting point of American mythology" (Slotkin)--Cast Puritan experience of the New World in terms of the archetypal drama of the Bible, thereby adapting Old World mythology to a new setting. 1. Jeremiad and the national covenant: State genres: threat derived from typological parallels linking the Puritans to the Israelites, God's chosen people in the Old Testament, via a national covenant : Mary Rowlandson: 106A. Move to Winthrop section earlier: John Winthrop: "thus stands the cause betweene God and us, wee are entered into Covenant with him for this worke . . . If wee shal neglect the observation of these articles . . . the Lord will surely breake out in wrathe against us be revenged of such a perjured people and make us knowe the price of the breache of such a Covenant" (Spring Reader 265) John Cotton: "looke well . . . to your children, that they doe not degenerate as the Israelites did; after which they were vexed with afflictions on every hand" (Spring Reader 251). 2. conversion narrative and the personal covenant: personal convenant and the search for spiritual knowledge and identity. National Covenant is worked out on the personal level; personal salvation linked to national redemption. Indian captivity as bondage of the spirit to the flesh--individual psychology of conversion, the personal covenant--captivity as the conversion narrative: innocent complacency disrupted by descent into doubt and fear (note how this is expressed by physical separation and journey in MR); trial and ordeal leads to despair; redemption by faith; revelation and a new state of assurance; rebirth into a "new man." 3. Family and the State: Joseph Rowlandson, 160-62. The connection between personal and national convenants linked the individual to the state/nation/community through a shared spiritual identity and destination: Election. This made the family and the State (private and public associations) replicas of each other. B. Expressed Separation Anxiety (physical separation from the community = isolation and despair; spatial dispersion = spiritual degeneration): Captivity narrative translated the emigrants' anxiety about crossing the Atlantic to an anxiety about crossing the border of the town. The captive's anxiety about being Rowlandson Lecture (F05Rowl Lec Notes), p. 4 isolated from the community expressed a more general anxiety among the Puritans about being isolated from England and their families at home. Compare Cotton and Winthrop's reference to the anxiety of separation to Rowlandson's despair at being captured: "all was gone . . . gone. . . gone . . .I must turn my back upon the town, and travel with them into the vast and desolate wilderness, I knew not whither. . . . (71x, whole section is great) C. Confronted the Frontier Captivity narrative contained the anxiety and real threat of life on the frontier: degeneration and dispersion from one's community raised the threat of "going native" i.e., outside the Law of the State, or, even worse, the possibility of the "social instinct" to form new associations with others. 1. safe contact effect of contact with Indians was safe because forced, not desired, therefore satisfied a curiosity about the wilderness without representing it as desirable 2. trial and judgment adversity and adventure were represented as spiritual trials and judgment, and so became a means for reinforcing the very laws and associations that were abandoned when one crossed the border into the wilderness 3. borders confirmed the importance of physical community, the town-limit, by transgressing it 4. sex and racial difference confirmed the significance of sexual/racial boundaries by threatening to transgress but not. Sexual temptation was viewed as a threat to the internal harmony of the community (hence severe penalties for adultery, premarital sex) and to the racial boundary between "Red" and "White," a division that was only beginning to emerge (vs. the more predictable one of differences in customs, degree of civilization). The threat always there, but especially acute for women. No rape: "Not one of them offered the least imaginable miscarriage to me" (84); "not one of them ever offered me the least abuse of unchastity to me, in word or action" (107C). Note the drunk Quinnan chasing his old squaw around the wigwam: 104A. He does not bother Rowlandson. D. A New Way of Representing Women's Experience 1. Power and visibility women were very powerful in the colonies and often ran the domestic economy (the home, education of children, household trade, etc.), but they had no formal political authority: usually not allowed to speak in Church, did not hold public office, etc., legally subordinate to their husbands, brothers, even sons. The captivity narrative give them setting in which that power could be exercised. Rowlandson Lecture (F05Rowl Lec Notes), p. 5 a. Hannah Dustin an obvious example of that. E.G. of Hanna Dustin, pp. 16668: She is not protected by the Law, therefore the Law does not prohibit her from killing her enemies: 167-68. b. Note the Gov./State sanctions her act. Consider Weetamoo (Quinnan's squaw and MR's mistress) and Rowlandson: two very powerful women, subordinate to their husbands, but eminent in their communities and dominant in domestic affairs 2. Speech and authority Captivity narratives gave women a discursive role to occupy, narrativized their social and cultural importance in way that was not otherwise available to them. This gave them an opportunity to speak, or write, publicly about their experience in a way that made it valuable and significant to the community. At the same time, that speech was also interpreted at the time as a violation of the social norms, and the experience it described could not always be fitted into the status quo. We saw how careful Cotton Mather is to “contain” Hannah Dustin’s actions. Some say the emergence of women’s voices, like the heightened visibility of their experience literally outside the boundary of normal social life, inevitably work against the drive to reincorporate her experience into the community of saints at the end, that they demonstrate an interest in individual experience, a woman's experience, that suggests an autonomy and independence that is incompatible with the rhetoric of spiritual subservience and Woman’s place in the Family and State. This tension is evident in Rowlandson’s narrative, and she responds to it in several ways. a. women's speech and the threat of dissension Therefore created tension about the woman's authority to speak: Fitzpatrick claims this tension between corporate and personal salvation was especially acute in narratives of women, but Rowlandson's whole strategy is to dissolve her "self" in favor of corporate narrators figured by the Bible. "Some are ready to say, I speak of it for my own credit; but I speak it in the presence of God, and to his glory" (107B) b. typological authority and women's speech as exemplum she is an eye-witness, thus invoking the eye-witness authority we have seen so often this quarter since Columbus: "Now is that dreadfull hour come, that I have often heard of . . . but now my eyes see it." But to the authority of the eyewitness she adds something else: notice that she says the one person out of 37 in the garrison who escaped death or captivity "might say as he in Job 1:15, 'And I only am escaped to tell the news.'" We will see that gesture throughout the narrative, i.e., rather than speaking only about herself, or as herself, she will quote a passage from the Bible and let the speaker in that passage speak for her. This typological parallel between her own situation and that of (in this case) David in Psalms allows her to see the spiritual significance of her visible Rowlandson Lecture (F05Rowl Lec Notes), p. 6 condition (e.g. p. 74 A) and to associate herself with the spiritual community of God's people, the Elect. To reinforce that context, and make the narrative “safe” as a reinforcement of the status quo, there is a preface by a leading male Puritan minister (Increase Mather), which oddly focuses on Joseph Rowlandson and subordinates MR’s personal voice to her role as model wife, member of the community, and Puritan Thus the captivity narrative performed an important social function: it reinforced the boundaries of the State (physical, moral, social, spiritual) right at the edge of the wilderness. In Freudian terms, we could say it sublimated the fear and anxiety—and the powerful appeal—of contact with the Indians into a form that was compatible with the State. But sublimation is notoriously fragile, and as we have seen this cultural work was very complex and delicate. As a result, it often failed to work, or work completely, and as a result gives us a glimpse into life on the frontier that is not so easily accommodated by the symbols, customs, and practices of the English Puritan community. That is the thesis for my reading of MR's narrative. IV. A Narrative of Dissociation and Association Fundamental paradox of the captivity narratives: captivity starts through dissociation of MR from her house, town, and family, and her isolation. It was led to the re-association of the captive with the community, and reinforced that connection through an increased awareness of one's identity as a Christian woman/man. A. Captivity as Redemption As the title of the American edition suggests, the whole experience of captivity is set within the context of MR's redemption from the beginning. She relates her time as a captive from the point of view of one who has been redeemed, and she constantly compares her experience in captivity to her attitude before she was captured to contextualize her experience within the ideological framework of the State. 1. divine intervention disrupts her complacent life: the attack on Lancaster a. natural order disrupted, family dispersed, town destroyed : the dogs don't bark; what might normally be hail and rain are bullets; there is no respect for nursing children, or women. Rowlandson begins with a vivid and horrible account of the attack. The graphic quality of the violence in her description is a direct appeal to pathos: it is supposed to shock you, to disrupt your complacent view of the world, and open your eyes to a spiritual significance beyond the visible world. b. translates the attack into typological terms as a spectacle staged by God for our edification: eyewitness as type Rowlandson Lecture (F05Rowl Lec Notes), p. 7 As she says "Now is that dreadfull hour come, that I have often heard of (in time of war . . . ) but now mine eyes see it": READ p. 69-A. The whole scene is treated: READ p. 70A "Oh!, the dolefull sight that now was to behold at this house! Come, behold the works of the Lord, what desolations he has made in the earth" (p. 70). 2. Descent into despair: gone, gone, gone 71X; then gone from God: 74X Pit of Despair: pivotal moment in conversion narratives: The Fourth Remove dramatically demonstrates the importance of this typological parallel between her situation and that of God's people in the Bible. It begins with Rowlandson being plunged into utter despair: she is separated from her daughter Mary, never to see her again until they were both freed; and she is separated from other members of her family and friends who had been captured with her. Rowlandson tells us that she hears one of the women was killed along with her child and both are burned to death. Rowlandson is at rock bottom, but while she cannot express what she is feeling to men, the Lord helps her by letting Jeremiah the profit speak for her: READ 78-A. Thus, what is inexpressible in a worldly situation is perfectly expressed through scripture; her experience represented literally by a typological parallel with the Bible. This tends to deemphasize the individuality of her experience and its specificity to the American wilderness, while automatically situating her as a member of the community of the Elect. Therefore MR will be an example to the whole community (67A) rather than a contradiction to women's roles. a. benefits of affliction : it helps her understand the Bible: 93-94, examine her ways (91), etc. Compares herself to David in Psalms, "It is good for me that I have been afflicted." b. subject to God's will: At no time does she ever claim to seize the initiative or act independently to improve her condition (1) captives have to await God's will: 77 NB: the absolute predestination of her captivity: God preserves the heathen and inhibits the English army because the captives "were not ready for so great a mercy as victory and deliverance": 80. Note how historical events wait on the providential plan and the process of conversion. The colonists had not yet sunk far enough into despair to see the truth of God's benevolence toward them. (2) she refuses individual initiative in favor of providence She claims that she refused to escape when she had the chance because she wanted to wait for "God's time": READ 107A. This abdication of individual initiative in favor of providence is similar to her abdication of the narrative voice in favor of typological parallels--both subordinate the individual body to divine spirit. 3. Redemption and reunion Rowlandson Lecture (F05Rowl Lec Notes), p. 8 Released from captivity, she returns to the community and is reunited with her family-except six-year old Sarah, who was buried in the woods. That all reflects the renewed spiritual association she experiences with God. She re-casts the story in terms of a conversion experience: READ 111-12: complacency, disruption, trial, revelation, assurance. B. Captivity as Adventure: the frontier How complete is that return to the community? Little Sarah is buried out there in the woods, and when her neighbors are sleeping, Mary is awake weeping. Did Mary's captivity change her in other ways that she does not tell us, maybe even that she is not aware of herself? And has that made it impossible for her ever to be completely re-integrated into what used to be her community? Although MR represents her captivity as reinforcing the State and her place in it, there are elements of her narrative that pull our attention in other directions, towards dissociation from the Puritan community rather than re-association with it. Part of that “pull” takes place through MR’s implicit recognition of Indian society as an alternative to her own, another civil State, not simply dismissed as “savage” and “uncivilized.” In other words, MR shows us the social instinct alive and well among the Indians. Is she “instinctually” drawn to that other State? 1. Acts of kindness (a) the kindness of God The Indians do treat her humanely at times, but MR usually dismisses it as a arbitrary or personal idiosyncrasy of a particular Indian. That strips the act of any significance as part of a larger social system and set of values that might be the basis for an alternative form of association—i.e., viewing the Indians as a “State” or “family” or community. She almost always reads acts of kindness as sign of God's direct intervention in her plight, and as a result of His generosity: 79A (Cf. 93, where they build her a shelter but they sleep in the rain, and she attributes that to the Lord's mercy.) The care with which she presents these acts of kindness are an attempt to keep the contact “safe,” with the Law. It reflects her hatred of any suggestion that the boundary between English and Indian can be crossed productively: hatred of the Praying Indians: 98 That ambivalence, which is often expressed in wild swings from accounts of kindness to accounts of brutality, is also expressed in the exaggerated hatred of the "Praying Indians" because their hybridity, as converted Indians, suggests closer contact between the two sides than Rowlandson can accept, i.e., the very idea of "conversion" in that sense suggests that the culture AND SPIRITUAL boundary between the English and the Indians is not so secure as she would hope. Disappointment at being fooled by Indians dressed as Englishmen: 94Q (b) the kindness of Indians Rowlandson Lecture (F05Rowl Lec Notes), p. 9 Nine days after the attack, in the middle of a New England winter, through the snow, with no food, her child finally dies (75). But there are odd moments of sympathy demonstrated by the Indians, with no comment from Rowlandson: after making her leave the dead child, they then bury her daughter Sarah (75), not easy to do in frozen ground. One of the Indians, fresh from killing and plundering the town of Medfield, brings her a Bible (76). They "favor" her because of her wound, not making her carry as much as others (79). They comfort her a bit when she weeps in front of them for the first time (82). She repeatedly seems moved by that kindness in a way that would undermine the absolute difference between her and them. Finally, in the ninth remove, she describes a squaw as being kind to her, with no reference to God: READ 84-5A. At such moments, the Bible often disappears from the narrative, and the scene is presented as two women connecting at a personal level. Her master's oldest squaw also shows her "kindness" (97). See also p. 101A-kindness, appreciated, now even while the Englishmen's bloody clothes lie behind her! 2. economic exchange She makes a couple of shirts for another Indian, who gives her a knife, that she then gives her master and is happy that he will accept it: Stockholm syndrome? Acculturation? 3. social exchange (a) tastes She gradually becomes accustomed to the food during her captivity, and actually develops a taste for it, even to the point turning against her “own kind.” She eats the raw horse liver with blood on her mouth, she appears as a savage: 81. Eats boiled horse-feet and guts, and says about it with Jonathan of the Bible, "this honey" (95). In the next remove, she actually takes some horse-foot from the mouth of a and English child: READ 96. (b) the dinner party: Refuses to smoke with King Phillip, but for personal reasons; reduces the big cultural contact to a reflection on her weakness for tobacco: 82. He pays her to make a shirt for his boy, is invited to dinner with him and loves the bear-grease pancake, which is the best tasting "meat" she has ever had. She then invites her master and mistress to dinner and observes her mistress's snobbishness.: 83 This is an implicit recognition of the Indian society as structured around rules of association, and hence in that way at least equivalent to the Puritan society as a human civilization. (Note the way she is reproducing her paradoxical status as the wife of a minister and daughter of a wealthy landowner: she hosts a dinner and scorns the visiting wife, but is subservient to the male power.) (c) sluttish tricks The Indians are often disgusted at her manners: she uses her own dish to dip their water (93), she serves her master and mistress out of the same dish (83B), etc. Master and mistress are Rowlandson Lecture (F05Rowl Lec Notes), p. 10 disgraced by her begging (96). NB here Rowland's sensitivity to—and hence at least recognition of—Indian manners as a system of etiquette different from hers, AND from that perspective SHE is inferior. 4. fashion Rowlandson clearly has a taste for Indian finery. She reports fancy dress in great detail, lingering over it. (Cf. her more general curiosity about their rituals: preparing for the battle at Sudbury: 100. This is presented absolutely straight-forwardly, almost as an anthropologist would describe it, even though it is preceded by her hateful account of some Praying Indians. She hates them more than her captors. Why? Is it because they are hybrids, as she is terrified of becoming?). dressing for the dance: 103 Weetamoo’s finery: 97 5. going home (MexBoy image/two paths) This description of Weetamoo immediately follows a scene in which the Indians tell MR to clean herself up because she is going home: the mirror scene, 96-97. The mirror scene: She clearly is quite a sight: she has not washed for a month, she must look like a "savage." Esp. note the contrast between unwashed Mary and the dressed up Squaw in the next paragraph (Weetamoo's toilet and vanity, "as any of the gentry of the land" (97). But Mary is oddly silent about what she sees in the mirror. Is it the image of a hybrid, a mestiza, and as such cannot be recognized by her? Or recognized, but not named? How close is she to becoming a hybrid like the "praying Indians," whom she hates? Which road has she really taken? The road to Boston? Or the road to Metacom’s fort? End with two images: the path to Philip's fort, and an image of Boston where Mary is living at the end. Little Sarah is still out there in the woods. Does Mary think about her when she's warm in bed at night? And when Mary looks at herself in the new mirrors in her house in Boston, does she ever see what she say, but would not describe, in the mirror that Metacom handed to her before her release? What she sees is the new figure on the historical stage, a hybrid, both Indian and European (British), and yet neither: the American. This new figure will quickly become a symbol for the emergence of a new State—the United States of America—that