Non-steroidal Therapeutic Options for Treating Wheezy Infants and

advertisement

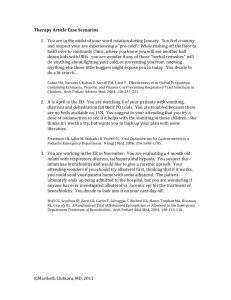

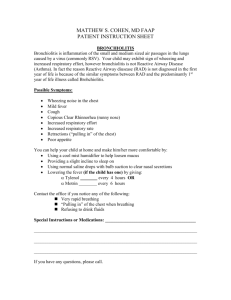

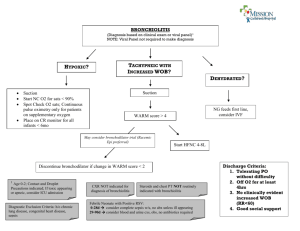

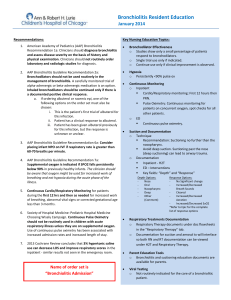

NON-STEROIDAL THERAPEUTIC OPTIONS FOR TREATING WHEEZY INFANTS AND TODDLERS GIOVANNI PIEDIMONTE and MIRIAM K. PEREZ Department of Pediatrics and Pediatric Research Institute West Virginia University School of Medicine, Morgantown, WV, U.S.A. CORRESPONDENCE Giovanni Piedimonte, M.D., Department of Pediatrics, West Virginia University School of Medicine, 1 Medical Center Drive, P.O. Box 9214, Morgantown, WV 26506-9214, Telephone: (304) 293-4451, Fax: (304) 293-4454. Email: gpiedimonte@hsc.wvu.edu 1 Introduction The following paragraphs review non-steroidal therapeutic agents commonly used for treating infants and toddlers with wheezing, which, in the absence of structural airway abnormalities, is almost always triggered or caused by an acute respiratory infection. This review deals in particular with the management of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infections, because this virus is by far the most common etiologic agent in this age group, and also the focus of most available literature in the field; however, because of the lack of effective virus-specific therapeutics, the pharmacological management of virus-induced wheezing in early life is quite similar independently from the specific infecting agent. In general, pharmacologic interventions in this setting are adopted by physicians based on anecdotal experience or lack of alternatives, and despite the lack of evidence-based efficacy data. Although a few alternative approaches have been tested in humans and hold some promise for the future (e.g., anti-leukotrienes), the antiviral compounds and putative vaccines currently being developed are not likely to become available for clinical use in the near future, and therefore were not included in this review. Bronchodilators Bronchodilators are frequently used in infants with wheezing associated to viral infection; however, their routine use remains controversial and most randomized controlled trials (RCT) have failed to find objective evidence of clinical benefit. Albuterol – Some small RCT have shown a possible benefit to the use of albuterol in viral lower respiratory tract infections (LRTI). Schuh et al. evaluated 40 infants between 6 weeks and 24 months of age with a first episode of wheezing and signs and symptoms of bronchiolitis. The infants were randomized to receive nebulized albuterol vs. saline as 2 doses 1 hour apart. In this study, the authors demonstrated improvements in work of breathing and oxygenation after two doses of albuterol. In another study, Schweich et al. evaluated the efficacy of nebulized albuterol in infants under 2 years of age 2 who were seen in the emergency department for first time wheeze due to LRTI. Twenty five infants were randomized to receive nebulized albuterol or saline placebo. Significant improvements were seen in wheeze and oxygenation scores of those infants receiving albuterol, although oxygenation did not improve until after the second dose; in fact, there was a decrease in oxygen score after the first dose of albuterol and there was no difference in respiratory rate or heart rate. A significant shortcoming of both studies is that the patients were not followed over time; consequently neither study demonstrated an improvement in length of stay (LOS) or improved resolution of symptoms. Several other studies have demonstrated the opposite to be true, i.e., that albuterol offers no consistent benefit in patients with bronchiolitis. Klassen et al. enrolled 83 infants in a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial to evaluate nebulized albuterol vs. placebo. Outcomes measured at 30 minute intervals included respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, wheezing and retractions. The authors found short-term improvement in clinical scores 30 minutes after a single albuterol nebulization; however, no difference was seen between the two groups 60 minutes after the treatment. Gadomski et al. evaluated infants presenting to the emergency department with a first episode of wheeze. Eighty-eight infants were randomly assigned to receive two nebulized albuterol treatments or nebulized saline 30 minutes apart, or a single dose of oral albuterol or saline placebo. Among the four groups, no difference was seen in respiratory rate, heart rate, clinical score, oxygen saturation, or level of wakefulness. A 1992 meta-analysis evaluated several outcomes among 8 clinical trials (1). This review found no improvement in hospitalization rate or respiratory rate associated with the use of albuterol. There was a statistically significant, but clinically insignificant, improvement in oxygen saturation and heart rate. The authors concluded that there is no evidence for the efficacy of β2-agonist therapy in viral bronchiolitis. Studies in animal models have suggested that single-isomer preparations like levalbuterol may have a better anti-inflammatory effect than racemic albuterol in virus-infected airways, but this has yet to be confirmed in clinical trials. In summary, albuterol has not been shown to have consistent benefits in the treatment of viral bronchiolitis. A carefully monitored trial in individual patients may be warranted, with discontinuation of therapy if no objective improvement is noted. Racemic Epinephrine - As with albuterol, there is no strong evidence to support the use of nebulized racemic epinephrine in the treatment of viral bronchiolitis; nevertheless, it is frequently used in infants with airflow obstruction. Kristjansson et al. found an improvement in oxygen saturation at 30, 45 and 60 minutes after inhalation of nebulized epinephrine, but this failed to improve the overall clinical course. More recently, a large RCT compared nebulized epinephrine administered every four hours to placebo in 194 hospitalized infants with bronchiolitis. No improvement could be demonstrated in length of stay, respiratory and heart rates, work of breathing, or length of oxygen therapy. In intubated infants with bronchiolitis, inhaled racemic epinephrine has resulted in a significant reduction of airway resistance, but without improvements in oxygenation. Several studies have compared the efficacy of nebulized albuterol against epinephrine. These studies indicate that racemic epinephrine may have an advantage over albuterol in the prevention of hospitalization and reduction of work of breathing. However, the Cochrane analysis of available data found lack of evidence to support the use of epinephrine in the inpatient setting (2). While evidence-based protocols do not support the routine use of albuterol or epinephrine, the use of bronchodilators on a trial basis in select patients is acceptable. If clinical improvement can be documented, then continued use can be recommended. However, treatments should be discontinued if no improvement is demonstrated, because of the possible side effects (e.g., tachycardia, tremor, hypokalemia, hyperglycemia). As epinephrine is typically not prescribed for use at home, albuterol may be a more appropriate choice for outpatient use. Anticholinergic agents - Anticholinergics like ipratropium bromide have not been found to be effective in the treatment of viral wheezing. Several studies have evaluated ipratropium alone and with albuterol. 4 While minor improvements in oxygenation have been reported, there is no consistent, significant benefit to the overall clinical course or outcome. Antibiotics It is not uncommon for infants with virus-induced wheezing to receive antibiotic therapy. It is estimated that antibiotics are used in 34 to 99% cases of uncomplicated bronchiolitis. This therapy is frequently started because the patient is febrile, but fever per se cannot reliably differentiate viral from bacterial infections. In fact, the risk of bacterial superinfection in infants with bronchiolitis and fever is quite low (0.2%), even when body temperature is >39˚C. However, for intubated infants with severe bronchiolitis, the rate of secondary bacterial infection is much higher, and may be as high as 26%. When a secondary bacterial infection is diagnosed, the most common sites are the urinary tract and the middle ear. In particular, infants with secondary infections are more likely to have a urinary tract infection than bacteremia or meningitis (12% vs. 0.43%). Acute otitis media is also seen as a complication of respiratory infections (57-67%), but its presence does not seem to influence the severity of fever, respiratory distress or the overall clinical course of the disease. In one series, evaluation of middle ear aspirates in children with bronchiolitis revealed RSV in 17 (71%) of 24 patients. In addition, all patients with acute otitis media had bacterial pathogens isolated, the most common being Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis. If present, otitis media should be managed according to current AAP recommendations. Several prospective RCTs have evaluated the clinical outcomes of infants who received antibiotics for the management of bronchiolitis. As early as 1966, a doubleblind RCT failed to demonstrate a benefit to treating bronchiolitis with antibiotics. Friis et al. evaluated 136 children between the ages of 1 month and 6 years and found no difference in the course of the acute illness, fever relapse, or pulmonary 5 complications in those patients with bronchiolitis who received antibiotics when compared to those who did not. We conclude that antibiotics should be used in patients with bronchiolitis only when specific evidence of coexistent bacterial infection is present, and confirmed bacterial infections should be managed no differently than in the absence of bronchiolitis. Anti-Leukotrienes As discussed above, strong experimental evidence in animal models and a number of clinical studies indicate that cysLTs are released during viral infections and contribute to airway inflammation and hyperreactivity. Therefore, it would make sense if leukotriene antagonists would have therapeutic activity in the settings of acute bronchiolitis, and possibly prevent or reduce the recurrence of wheezing episodes post-bronchiolitis. The first pilot trial testing this hypothesis was conducted in Denmark by Bisgaard et al. (3). One hundred and thirty children hospitalized with acute RSV bronchiolitis were randomized into a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of the cysLT1 receptor antagonist montelukast given for 28 days starting within 7 days of symptom debut. Children on montelukast had significantly less symptomsfree days compared with children on placebo (22% vs. 4%); in particular, daytime cough was significantly reduced on active treatment and exacerbations were delayed. This study generated a lot of interest and hope in the use of leukotriene modifiers in viral bronchiolitis despite its several limitations, especially the small sample size and wide age range (3 to 36 months old). To address the latter, the author conducted a post-hoc analysis of the same data revealing that the effect of montelukast was larger in the younger children compared with the older children, which was consistent with previously reported data on the age-dependency of cysLTs production (4). To address the issue of statistical power, a larger multi-center double-blind study of 979 children 3 to 24 month old with RSV bronchiolitis was completed recently (5). This time, no significant differences were seen between 6 montelukast and placebo in symptoms-free days. However, post-hoc analysis limited to the 523 patients with persistent symptoms showed more symptoms-free days in the montelukast group. Therefore, additional studies are necessary to define conclusively the role of leukotriene modifiers in the management of patients with more persistent or more severe respiratory symptoms following viral infection. Furthermore, it would be important to compare the effect of anti-leukotriene therapy during the infection with its prophylactic use starting before the viral season, and also assess its effect on the incidence of post-viral asthma. References 1. Flores, G., and Horwitz, R.I. 1997. Efficacy of beta2-agonists in bronchiolitis: a reappraisal and meta-analysis. Pediatrics 100:233-239. 2. Hartling, L., Wiebe, N., Russell, K., Patel, H., and Klassen, T.P. 2004. Epinephrine for bronchiolitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev:CD003123. 3. Bisgaard, H. 2003. A randomized trial of montelukast in respiratory syncytial virus postbronchiolitis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 167:379-383. 4. Piedimonte, G., Renzetti, G., Di Marco, A., Auais, A., Tripodi, S., Colistro, F., Villani, A., Di Ciommo, A., and Cutrera, R. 2005. Leukotriene synthesis during respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis: Influence of age and atopy. Pediatr Pulmonol 40:285-291. 5. Bisgaard, H., Flores-Nunez, A., Goh, A., Azimi, P., Halkas, A., Malice, M.-P., Marchal, J.-L., Dass, S.B., Reiss, T.F., and Knorr, B.A. 2008. Study of montelukast for the treatment of respiratory symptoms of post-respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis in children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 178:854-860.