EPISTEMOLOGY

advertisement

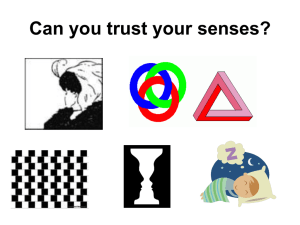

EPISTEMOLOGY Greek: Episteme = knowledge Logos = science/theory/study of Philosophical relevance: 1. Philosophy seeks truth, wisdom, and understanding. i. How do we know that we have obtained the truth? ii. Need to know the conditions of knowledge. 2. Seeking knowledge is irresistible to human beings. 3. Want to understand science. 4. Problem of scepticism. 1 Different senses of “knowledge” 1. Skill knowledge (“know-how”) X knows how to: walk, ride a bike, etc. May be unable to explain how it’s done. 2. Knowledge by acquaintance (familiarity) I know: John, this city, her voice, etc. Perception: I’m aware of this board. Animals have these kinds of knowledge. 3. Propositional knowledge (“know-that”) S knows that p. Propositions: true/false. I know that: 2 + 2 = 4, this is a chalkboard, etc. Requires cognitive ability to distinguish propositions. Epistemologists tend to focus on #3. Why? 2 Historical reason: Science Science is perhaps the most successful knowledge-gaining enterprise in history. Think of the advances made after learning: That F = ma That E = mc2 That the atom is composed of parts That humans evolved from animals Etc. Understanding how propositional knowledge is gained will help us to understand science. Is this a theoretician’s bias? Much of science depends on developing new experimental techniques. I.e., “know-how”. Have philosophers overlooked the importance of this? 3 Historical Reason: Intelligence Our uniquely human intelligence seems to be the result of our ability to represent and understand propositions. Classic view of the mind: Understanding is grasping propositions. E.g. knowing what snow is = representing to oneself all or most of the propositions about snow (that it is white, cold, melts at room temperature, etc.). Classic AI theory: intelligence = manipulation of symbols that represent propositions (“have content”). Problem: Machines programmed with millions of representations. When connected to a robotic body, couldn’t perform simple of tasks (avoid an obstacle, pick up an item, etc.). Is there more to intelligence than propositional knowledge? 4 Propositions Nonetheless, propositional knowledge is of central importance. Here’s why: It seems to be what’s special about humans (and perhaps higher primates, dolphins). I.e. we can form complex conceptions: Right/wrong; rational/irrational; true/false; matter/antimatter; etc. We make sophisticated claims about the world. E.g.: “It is irrational to act immorally”; “Everything is made of matter”. The ability to form such ideas underlies all of politics, science, law, philosophy, etc. So, evaluating these sorts of knowledge claims seems particularly important to understanding the human condition. 5 Propositional knowledge Key epistemological questions: 1. What is it? 2. Is it possible and if so, how? Historically a great deal of epistemology was stimulated by worries over #2: Is it possible to know anything? Descartes thought that investigating whether knowledge is possible teaches us what knowledge is. 6 Descartes: Scepticism to Rationalism The source of our knowledge appears to be the senses. But often the senses deceive us (e.g. about what is far away, illusions). Can I at least be certain that I am standing in a room, talking, looking at a window, etc? Descartes: No! You could be dreaming. There could be an omnipotent demon that constantly deceives you so that all your sense impressions are misleading. Contemporary version: Maybe you are a brain in a vat! Even what appears most certain might be misleading. 7 Radical doubt 1. In order to have knowledge we need to be able to tell the difference between a hallucination (deception) and a perception. 2. It is impossible to distinguish between a hallucination (deception) and a veridical perception. Therefore: 3. We do not know whether any of our perceptual beliefs are true. We don’t know whether anything exists at all. We have “lost the world”. 8 Certainty: not from the senses No matter how much I may be deceived, one thing cannot be doubted: That I am having some kind of thought (even a deceptive one). No matter how hard the Demon tries to deceive me, if it succeeds it follows of necessity that I exist at least enough to have thoughts, perceptions, desires, etc. So it is absolutely certain that I exist as a thinking thing. The senses did not give me this knowledge (see also: wax example). This knowledge came from reason alone. Rationalism: knowledge is derived from reason not sensation. Reason may use the senses as data. 9 Wax example I observe a piece of wax. It is: Solid, cold, scented, white. I approach the fire. The wax changes: Liquid, warm, scentless, clear. Every sensory property has changed. Descartes: If I know that it is one and the same piece of wax, this cannot be based on the senses. Even empirical knowledge does not come from the senses. Conclusion: Even empirical knowledge is derived from reason. 10 Rationalism and knowledge Descartes: That which cannot be doubted (“clear and distinct ideas”) must be true. Descartes’ solution to scepticism: 1. I cannot doubt that an omnipotent God exists. 2. I cannot doubt that God is benevolent. 3. Therefore, I am certain that God doesn’t deceive me. So, my senses must be trustworthy. Well, this seems quite unsatisfying. It seems quite possible to doubt God’s existence. It certainly seems possible to doubt God’s benevolence. But does the empiricist do any better? 11 Perception and empirical knowledge Descartes assumes that we can have a full array of perceptions without any objects to be perceived. What is certain is that we have ideas (internal) of external objects. What’s doubtful is the existence of the external (physical) world. This assumes that we don’t directly perceive the world. There is something intermediate between a perceiver and reality. The “idea” of an object is directly perceived, not the object itself. Why believe there are such intermediaries? 12 Hume and empiricism Hume: All we ever experience are sensations. These sensations are not of continuous bodies. E.g.: we don’t see objects when we close our eyes. So, our sensations cannot give us the idea of a permanent, physical reality. Can we infer that physical reality exists and causes our sensations? Hume: This would be unjustified. Since we only ever observe sense data, how can we conclude there is something else “beyond” them? 13 What about causation? But surely objects cause our sensations. Hume: causation is only known through observation. It applies to sensations: sensation A always followed by B. Therefore, we can’t claim it applies to the unobservable. I.e., we can’t know that continuing, physical objects cause anything! Let alone sensations. 14 Conclusion We should admit that the only reality is the reality of sense data (and minds?). Physical reality is a useful fiction. It helps us to organize and predict our experience. Physical objects are “phenomena” of perception. “Truth” = “accurate predictions”. Empiricism: all knowledge is derived from sensation. 15 Evaluating empiricism Strengths: Avoids murky talk of unobservable reality “behind” the sense data. Avoids scepticism: only commits to the existence of sense impressions, and we are certain that we have those. Problems: 1. Lost the world again. Reply: No: the only reality is sensory, so reality is quite intimately known to us. 2. How do physical objects persist when not perceived? Reply: Objects are bundles of actual and possible experience. The table persists when not perceived because if you were to look there you would see a table. Sub-problem: what’s a “possible experience”? 16 3. Sense data can be indeterminate (how many leaves on that tree?) but physical objects are not. Possible reply: objects are sometimes indeterminate. 4. Let A, B, and C be slightly different shades of red. I cannot distinguish A from B. I cannot distinguish B from C. I can distinguish A from C. This is possible, but how can empiricism explain it? 17 Some further thoughts on scepticism Descartes: I know that p only if p can’t be doubted. But do we need to accept this criterion? Is absolute certainty required for knowledge? In particular, on what basis do we assume that certainty is required? 18 Common sense and certainty In fact, our ordinary concept of knowledge is one that tolerates uncertainty. If it is 99% certain that p: It is possible (1%) that p is false. Still, can’t I know that p? Example: I claim to know that we are safe. Why? We are flying. Flying is safe: <0.001% of flights crash. Therefore, I know that we are safe. I claim both: 1. I know we are safe. 2. It is possible (though very unlikely) I am wrong. 19 Science and certainty Science never assumes that anything is known beyond all possibility of being wrong. Science proceeds on the assumption that anything might turn out to be false. But science is our best system of gaining empirical knowledge. So its standards ought to be good enough for everybody. So the crux of the issue is: is certainty required for knowledge and if so, why? If logical certainty is required, scepticism is hard to defeat. 20 Where does this leave us? We want to understand the nature of knowledge so it would be nice to determine whether knowledge is possible. Problem: scepticism. Two solutions: Rationalism: physical reality can be known, but only via reason. Empiricism: we can have knowledge of the world, but the world is not what we think it is. To adjudicate this dispute, we need to know just what knowledge is. Fortunately, our investigation into scepticism has given us some clues here… 21