Cardiac catheterization1 - Home

advertisement

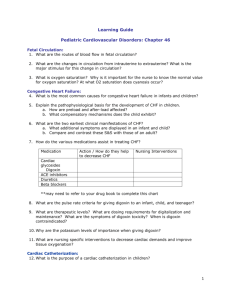

Cardiac catheterization is a procedure that produces special "pictures" of the arteries that supply blood to the heart (the coronary arteries) and of the main pumping chamber of the heart (the left ventricle). These images can reveal if one or more of the coronary arteries is blocked or if the left ventricle is functioning properly and pumping blood throughout the body. Additional information can be obtained about the pressure in the different chambers of the heart and about whether the heart valves are working normally or are leaky or stenotic. Who Should Have a Cardiac Catheterization? Some cardiologists regularly treat patients with cardiac catheterization and others treat patients with medications alone. No absolute rules exist, but there are some general guidelines that can help guide the decision to have cardiac catheterization. For most patients, the primary determining factor is whether a partial or complete blockage in the coronary arteries is present. The doctor and patient must decide whether these blockages should be treated with angioplasty (the balloon procedure) or bypass surgery. The patient must decide whether he or she is willing to undergo one of these revascularization procedures. If the patient is not willing, there is often little reason to undergo a cardiac catheterization. Generally accepted reasons for patients to undergo a cardiac catheterization include the following: Angina pains (i.e., the discomfort from blocked coronary arteries), which are not easily controlled with medication or that interfere daily life Chest pains of uncertain cause that repeatedly recur and defy diagnosis despite other tests Angina that occurs at rest despite medical therapy Recurrent angina after a heart attack Markedly abnormal stress test results Heart failure, when the suspected cause is coronary artery disease Disease of one or more of the heart valves causing symptoms such as shortness of breath Not everyone with angina needs a cardiac catheterization. Patients who have very rare or easily controlled episodes of angina may desire to continue with medical therapy rather than undergo angioplasty or bypass surgery. Many patients who have suffered a heart attack can initially undergo a stress test rather than cardiac catheterization. The risks of cardiac catheterization are low, but sound medical reason should always determine whether to undergo a cardiac catheterization procedure. Risks Factors Although cardiac catheterization is regarded as a relatively safe procedure, complications do occasionally occur. These can include: Bleeding at the site of sheath insertion. This commonly produces a small bruise in the groin, but, in rare cases, can lead to more serious internal bleeding. Infection at the site of sheath insertion Damage to the blood vessels in the groin Allergic reaction to the iodine-based dye Kidney damage and/or kidney failure Stroke Heart attack Death Occasionally, patients have an allergic reaction to the iodine-based dye used during cardiac catheterization. People who have had a previous reaction to intravenous dye or who have allergies to shellfish are at increased risk for allergic reaction. The doctor should be aware of the patient's risk for allergic reactions before performing the procedure. Such patients usually are given a steroid and other medications before the procedure to reduce the chance of serious allergic reaction to the dye. In rare cases, the dye used during the procedure can produce kidney damage, including kidney failure requiring dialysis. People with an increased risk for this complication include those with diabetes or preexisting kidney disease. Patients at higher risk of dye-induced renal failure are sometimes admitted to the hospital the night before the procedure to receive intravenous hydration beforehand. Good hydration before and during the procedure may decrease the chances of dye-induced kidney failure. In general, the risk for serious complications, such as stroke, heart attack or death, is very low — approximately one in 1000 in the general population. Before the catheterization procedure, the doctor usually will meet with the patient to perform an examination, ask about the patient's medical history, and discuss the procedure and its risks. In many cases, he or she will discuss the possibility of performing an angioplasty at the same time the catheterization is done, should the procedure reveal one or more blockages that require immediate treatment. These procedures typically are referred to as a "cath possible" or "on-line" angioplasty. Blood tests, including tests of the patient's blood counts and kidney function, and an electrocardiogram (EKG) usually are performed on the morning of the scheduled catheterization, although some physicians prefer to do these tests several days before the procedure. On the morning of the procedure, the patient typically is connected to an intravenous (IV) line to allow for the administration of fluids, to avoid dehydration, and for the administration of medications, if needed. Most patients are given a Valium-type sedative before the procedure, either in pill form or intravenously, to relax them and keep them as comfortable as possible while the cardiac catheterization is being performed. Patients who do not receive a sedative should feel free to ask the nurse or doctor for one; similarly, if the sedative dosage does not seem to relieve anxiety, the patient should ask for an additional dosage. In most cases, catheterization is performed through the patient's groin. To facilitate this, while the patient is in a presurgical "holding area," a nurse or technician will shave the area around the patient's groin. At the appropriate time, the patient will be wheeled into a specially designed laboratory and will lie down on a table. The groin area will be wiped with a sterilizing solution. Sterile drapes will be placed over the groin, and the area will be "numbed" by the doctor with one or two small needle injections of the anesthetic lidocaine into the skin. A pencilsized plastic tube called a sheath is then inserted into the artery that runs below the skin. Through it, differently shaped catheters can be passed up the artery towards the heart and into a coronary artery (see Figure 1). Iodine-based dye will be injected into the coronary arteries and pictures of the arteries will be taken with a special camera. A representative angiogram showing a tight stenosis (blockage) in the right coronary artery is shown in Figure 2. Another special catheter also may be inserted into the heart's left ventricle, through which iodine-based dye can be injected. This will enable the doctor to take pictures that show how well the left ventricle is pumping. Injection of dye during these pictures often leads to a "hot-flash" sensation throughout the body that lasts for 10 to 15 seconds. Pictures of the left ventricle taken during its "relaxation" and "contraction" phases are shown in Figure 3. The arrows indicate how the ventricle walls have contracted to pump blood out of the left ventricle. Additional information also may be obtained during the cardiac catheterization. A second pencil-sized plastic sheath may be inserted through a vein in the groin to accommodate another catheter. This can be threaded up to and through several of the chambers of the heart to measure pressures in different parts of the heart. It also can be used to measure the amount of blood that the heart pumps each minute. Doctors refer to this procedure as a "right heart catheterization." The entire cardiac catheterization procedure can be completed in as little as 15 minutes, although it occasionally can take an hour or longer. After the cardiac catheterization, the sheath or sheaths are removed from the patient's groin and pressure is applied to the area — usually for 5 to 15 minutes — to close off the holes in the blood vessels that were made by insertion of the sheaths. The patient will have to lie on his or her back for 4 to 6 hours to while normal blood clotting seals the holes in the vessels. Several new devices are available that allow the doctor to seal the hole made in the femoral artery immediately after the catheterization. One of these devices, called Perclose, enables the doctor to literally sew up the hole made in the groin. Two other devices, AngioSeal and VasoSeal, use collagen plugs to seal holes made in the femoral artery. If either of these two methods is used, the patient may be able to sit up within an hour of the procedure and begin walking within several hours. Most doctors who perform cardiac catheterization give the patient — and the patient's family — a preliminary report on the results immediately after the procedure is completed. Often they can tell right away whether they think treating with medication is possible, or if angioplasty (the "balloon procedure") or open heart surgery is necessary. Occasionally, the doctor may want to review films taken during the procedure with other doctors before making a final recommendation. Most cardiac catheterizations are performed on an outpatient basis, enabling the patient to enter the hospital early in the morning, undergo the procedure, and go home later the same day, often in the late afternoon or early evening. Occasionally, the doctor may feel it is advisable for the patient to stay overnight in the hospital, so patients scheduled to undergo a cardiac catheterization should plan to bring a small bag of select supplies, such as a bathrobe, slippers, and toiletries, with them. In all cases, the patient should not drive home, but should arrange for someone else to drive him or her after the catheterization. Before leaving the hospital, the patient will receive instructions from a doctor or nurse regarding when and to what extent he or she can resume normal activity. Most doctors advise against any heavy lifting or vigorous activity for several days, principally to ensure that blood vessels in the patient's groin heal properly. Other specific recommendations usually will depend upon what was found during the cardiac catheterization. A gauze dressing usually is taped to the area where the sheath or sheaths were inserted in the patient's groin. This is left on at the time of discharge from the hospital and usually can be removed by the patient the next morning. Taking a shower before removing the dressing can help loosen the tape and prevent discomfort. For several weeks after a catheterization, a small and relatively painless bruise or lump often is present in the area where the sheaths were inserted; the patient should call his or her doctor promptly if pain or tenderness develops. This can indicate infection or bleeding in the area or blood vessels that have not sealed off properly. Other symptoms which should prompt a call to the doctor include fever, shaking, or chills in the days after the procedure, which can indicate infection, or pain or discoloration in the leg, which may indicate damage to a blood vessel.