a before and after evaluation of acute kidney injury outreach

advertisement

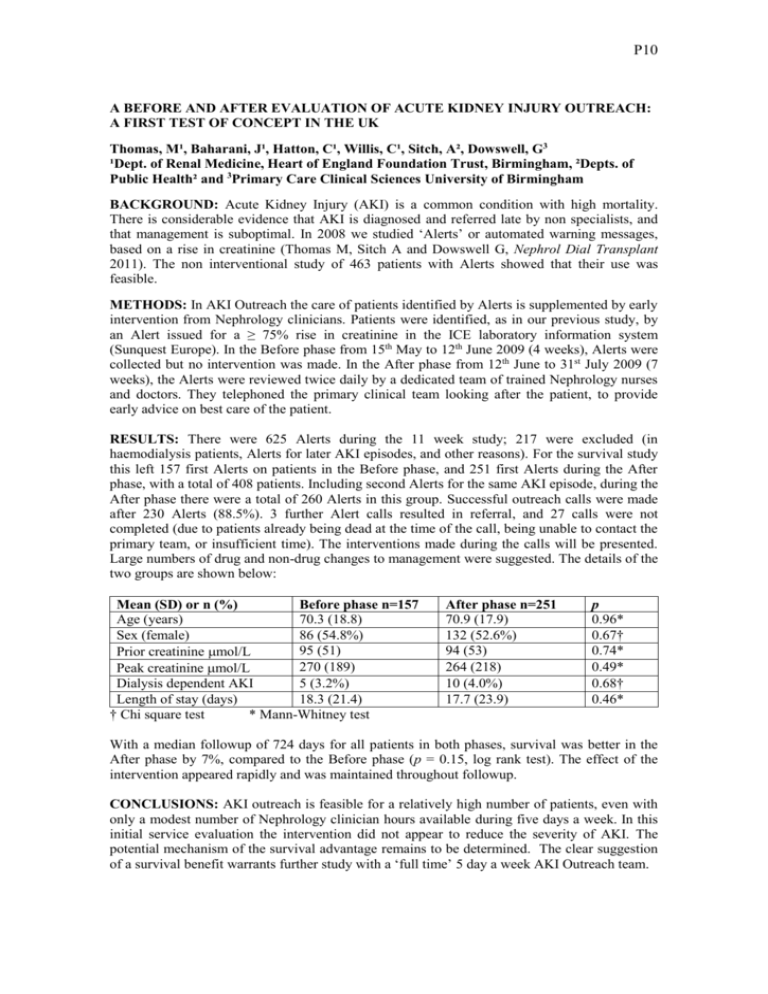

P10 A BEFORE AND AFTER EVALUATION OF ACUTE KIDNEY INJURY OUTREACH: A FIRST TEST OF CONCEPT IN THE UK Thomas, M¹, Baharani, J¹, Hatton, C¹, Willis, C¹, Sitch, A², Dowswell, G3 ¹Dept. of Renal Medicine, Heart of England Foundation Trust, Birmingham, ²Depts. of Public Health² and 3Primary Care Clinical Sciences University of Birmingham BACKGROUND: Acute Kidney Injury (AKI) is a common condition with high mortality. There is considerable evidence that AKI is diagnosed and referred late by non specialists, and that management is suboptimal. In 2008 we studied ‘Alerts’ or automated warning messages, based on a rise in creatinine (Thomas M, Sitch A and Dowswell G, Nephrol Dial Transplant 2011). The non interventional study of 463 patients with Alerts showed that their use was feasible. METHODS: In AKI Outreach the care of patients identified by Alerts is supplemented by early intervention from Nephrology clinicians. Patients were identified, as in our previous study, by an Alert issued for a ≥ 75% rise in creatinine in the ICE laboratory information system (Sunquest Europe). In the Before phase from 15th May to 12th June 2009 (4 weeks), Alerts were collected but no intervention was made. In the After phase from 12th June to 31st July 2009 (7 weeks), the Alerts were reviewed twice daily by a dedicated team of trained Nephrology nurses and doctors. They telephoned the primary clinical team looking after the patient, to provide early advice on best care of the patient. RESULTS: There were 625 Alerts during the 11 week study; 217 were excluded (in haemodialysis patients, Alerts for later AKI episodes, and other reasons). For the survival study this left 157 first Alerts on patients in the Before phase, and 251 first Alerts during the After phase, with a total of 408 patients. Including second Alerts for the same AKI episode, during the After phase there were a total of 260 Alerts in this group. Successful outreach calls were made after 230 Alerts (88.5%). 3 further Alert calls resulted in referral, and 27 calls were not completed (due to patients already being dead at the time of the call, being unable to contact the primary team, or insufficient time). The interventions made during the calls will be presented. Large numbers of drug and non-drug changes to management were suggested. The details of the two groups are shown below: Mean (SD) or n (%) Before phase n=157 Age (years) 70.3 (18.8) Sex (female) 86 (54.8%) 95 (51) Prior creatinine mol/L 270 (189) Peak creatinine mol/L Dialysis dependent AKI 5 (3.2%) Length of stay (days) 18.3 (21.4) † Chi square test * Mann-Whitney test After phase n=251 70.9 (17.9) 132 (52.6%) 94 (53) 264 (218) 10 (4.0%) 17.7 (23.9) p 0.96* 0.67† 0.74* 0.49* 0.68† 0.46* With a median followup of 724 days for all patients in both phases, survival was better in the After phase by 7%, compared to the Before phase (p = 0.15, log rank test). The effect of the intervention appeared rapidly and was maintained throughout followup. CONCLUSIONS: AKI outreach is feasible for a relatively high number of patients, even with only a modest number of Nephrology clinician hours available during five days a week. In this initial service evaluation the intervention did not appear to reduce the severity of AKI. The potential mechanism of the survival advantage remains to be determined. The clear suggestion of a survival benefit warrants further study with a ‘full time’ 5 day a week AKI Outreach team.