Africa 600-1450 - Newsome High School

advertisement

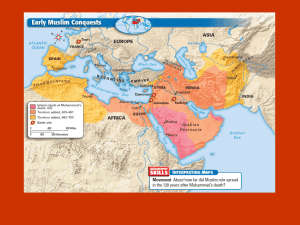

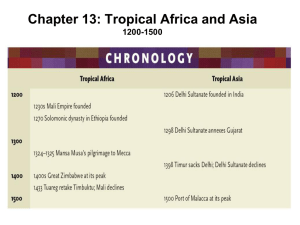

Africa: 600-1450 Malay seafarers colonized Madagascar between 300 and 500 CE, bringing with them bananas, which then became established in Africa and spurred fresh waves of population growth and migration … so that by about 1000 CE the millennia-long Bantu migrations had introduced agriculture and metallurgy to most of sub-Saharan Africa. The population of subSaharan Africa surged from about 3.5 million in 400 BCE to more than 22 million in 1000 CE. The widely prevalent political organization in Africa before 1000 CE was a system of kin-based, stateless societies that featured little bureaucracy to administer affairs. Instead, male heads of families made up a ruling council for a village, which might consist of only 100 or so people. A group of villages made up a district, which usually had no larger government. The most prominent family head was the chief representing the settlement when negotiating with neighboring peoples. Stateless societies did not disappear until the 19th century but much earlier than that, in th the 11 and 12th centuries, began evolving into larger chiefdoms. Necessitated by increasing conflicts as population rose, powerful chiefs overrode kinship groups in larger and larger districts. By 1200, chiefdoms were giving way to formal states called kingdoms. One notable feature of African society was the griot (GREE-oh), or professional storyteller. Griots chronicled the history and social customs of African societies through an oral tradition. They were also entertainers and sometimes even advisors to kings. Nomads crossed the Sahara desert for commercial expeditions in ancient and classical times, but after the camel was introduced from Arabia (and outfitted with a special saddle by the late centuries BCE), the pace of communication and transportation across the desert increased. After about 300 CE, camels replaced horses and donkeys as the preferred beasts of burden throughout the Sahara (and, for that matter, the deserts of central Asia). Caravans took 70-90 days to cross the Sahara from north Africa. After the 8th century, merchants from north Africa – already linked to the Mediterranean trade network – were mostly Muslim … so from that point on Islam profoundly influenced the development of sub-Saharan Africa. Slaves were a prominent feature of African society. Because there was little if any private property, individuals could only grow wealthy through the increased agricultural production that slavery made possible. Most slaves were prisoners of war, while others came from the ranks of debtors, suspected witches and criminals. In addition to agricultural work, slaves served as construction laborers, miners or porters. When the trans-Saharan and Indian Ocean trade networks expanded rapidly beginning in the 9th century, traffic in African slaves picked up as Muslim merchants provided access to markets in India, Persia, southwest Asia and the Mediterranean basin. Slave raiding within African then picked up as well, as rulers in large-scale states and empires began to make war on smaller states and kin-based societies to provide the captives for northern slave markets. Women in sub-Saharan Africa were subjected to the patriarchy found elsewhere, but generally had more opportunities open to them than did their counterparts in many other lands. Women enjoyed high honor as the sources of life. Occasionally they made their way to positions of power, and aristocratic women often influenced public affairs by virtue of their prominence within their families. Women merchants commonly traded at markets, and they participated actively in both local and long-distance trade. Sometimes they even engaged in combat and organized all-female military units. The arrival of Islam to Africa did not change the status of women nearly as much as it did in other parts of the world. For the most part, Muslim women in sub-Saharan Africa socialized freely with men outside their immediate families, and they continued to appear and work openly in society in ways not permitted to women in other Islamic lands. West African kingdoms Ghana (c. 500 to 1200) Ghana was a regional state beginning around 500 C.E., and with the increase in transSaharan trade (thanks in large part to the camel) its power and influence grew. It became an important commercial site and a center of trade in gold from the south, which it controlled and taxed, in return for ivory, slaves, horses, cloth and salt. This trans-Saharan trade is also often referred to as the gold-salt trade. As Ghana’s wealth and power increased, it built a large army funded by the tax on trade, which kept order and trade safe. In the 900s, the kings converted to Islam, which led to improved relations with Muslim merchants. Islam was not forced on the people, however, and traditional animistic beliefs continued to be important. Those who did engage in the trade often converted to Islam as well. After 1000, Ghana found itself under assault from northern Berbers and other tribal groups nearby, and was eventually absorbed by the West-African kingdom of Mali. Mali (1235 to late-1400s) During the period, the gold-salt trade continued to increase, and Mali controlled and taxed it all. The rulers honored Islam, and provided protection and lodging for merchants. Conversion to Islam was encouraged on a voluntary basis. The most famous emperor was Mansa Musa, who ruled from 1312 to 1337 and may well have been the richest man on earth at the time. A devout Muslim, Mansa Musa made his famous pilgrimage to Mecca (the hajj) in 1324-1325, taking along thousands of soldiers, attendants, subjects and slaves, as well as hundreds of camels carrying satchels of gold, which he doled out as gifts all along the way. When he returned to Timbuktu, the political capital of Mali, he built libraries, Islamic schools and mosques throughout the kingdom. Timbuktu thus became a rich Islamic cultural center for all of West Africa. Christianity in North and East Africa Many Africans in the northern part of the continent converted to Islam after 700, yet there remained a significant Christian tradition in Egypt and Ethiopia. Saint Mark is believed to have preached to the East Africans much earlier during the Roman period. Ethiopia evolved intoa kingdom with strong Christian traditions, developing a unique style of art and architecture. There is a strong monastic strain in both Ethiopian and Egyptian (or Coptic) Christianity. East African City-States As the trans-Saharan trade was to West Africa, the Indian Ocean trade was to East Africa. Bantu people had settled on the coast, and they interacted with Arabic sailors and merchants to create increasingly prosperous city-states such as Mogadishu, Kilwa and Sofala. These and other thriving ports along Africa’s east coast are often referred to collectively as Africa’s Swahili Coast, named after their language, a blend of Bantu and Arabic. Islam thus became implanted along the Swahili Coast in much the same manner it became implanted in West Africa – by Muslim-dominated trade, which included gold, slaves, ivory and exotic animal skins in exchange for Persian carpets, Arabian glass, Indian cotton textiles and Chinese porcelain and silks. In the 1200s, the kingdom of Zimbabwe in southeast Africa created a magnificent stone complex known as Great Zimbabwe, which was a city of stone towers, palaces and public buildings. The ruling elite and wealthy merchants of East Africa often converted to Islam, but did not completely give up their own religious and cultural traditions. For the rulers, Islam amounted to an expedient for political legitimacy and effective alliances.