Oct 28 2009 - The Origins

advertisement

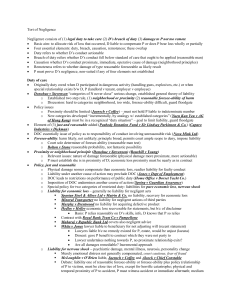

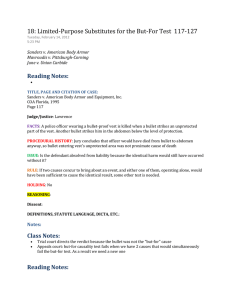

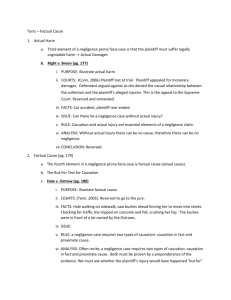

TORTS I 10.28.09 Class Notes Mastering Torts Casenote 4lawnotes.com o 1. Was the plaintiff's conduct in Williams v. Steves Industries, Inc. a but-for cause of the accident? Explain. Can there be more than one but-for cause of an accident? o Sine Qua Non: The “But For” Test Yes, the s conduct can be construed as a “but for” cause of the accident the court held that an award of damages for the death of the s children had to be reduced by reason of the s comparative negligence, since but for the s negligent failure to keep gas in the car, the car would not have stalled on the highway where it was foreseeably struck by the s truck. o Yes, there can be more than one “but for” cause of an accident o 2. How much “foreseeability” is required before tortious conduct will be found to be a proximate cause of resulting harm? o There should be an element of possible foreseeability to establish proximate cause o 3. What is the rule that comes out of Reynolds v. Texas & Pacific Ry.? What effect does post hoc ergo propter hoc have on the court's reasoning? Is expert testimony necessary to establish that lack of light multiplies the chances of a fall? o A is not required to establish causation in fact with absolute certainty; it is sufficient that the evidence shows that the s conduct more likely than not brought about the accident o Post hoc ergo propter hoc It is not enough that negligence of the employer and injury to the employee coexisted, but the injury must have been caused by the negligence o 4. Compare Reynolds with Kramer Service, Inc. v. Wilkins and distinguish the substantial factor (but-for) test from the evidentiary standard applicable to proving substantiality. o A careless reading of Reynolds and Kramer may lead one to conclude that not only must the s tortious conduct have multiplied the chances of harm to the , it must have multiplied those chances so much that harm was more likely than not to occur o Reynolds (p.117) s conduct cannot be a substantial factor (ie a factual or but for cause) unless it multiplies the chance for harm As to how much they must be multiplied, nothing more can be said than that the increased chances of harm must usually rise to the level where they make an indispensible (i.e. “but for”) contribution to the harm o 5. If the plaintiff in Saelzler v. Advanced Group 400 did not get a good look at her attackers, how could she prove that they were unauthorized intruders, rather than tenants of the complex? As a matter of public policy, why does the plaintiff have the burden of proving factual causation? Is it consistent with tort law's goal of compensating innocent victims? o She couldn’t prove who actually committed the crime but the proof of liability on the isn’t determined by who, whether authorized or not, committed the crime but whether the was negligent in providing sufficient security measures to protect its residents from all threats on the property. o 6. What is the rule that you are able to derive from Anderson v. Minneapolis, St. Paul & S.S.M. Ry.? o The s property was destroyed by (a) a fire negligently started by , (b) another fire of uncertain origin, or (c) a combination of the two fires. To recover from , the was not required to prove that but for the ’s negligence the harm would not have occurred. If ’s fire was a “substantial element” in causing the ’s damage, libability could be impose o If one negligently sets a fire which combines with another fire of no responsible origin, he is liable if his fire would have caused the damage independent of the other fire, or if his fire materially caused the damage. In other words, if one’s negligence would have caused the damge complained of, he is liable and it is irrelevant whether, in fact, another force combined to cause the damage o 7. Simultaneously, A stabs B with a knife and C fractures B's skull with a rock. B dies, and either wound alone would have been fatal. Can A or C be held liable for the death? Explain. o Both are held liable o 8. Analyze and be able to describe the “cases” at J&G page 367. o Case 1 Denise’s negligence was not a but-for cause. Denise is not liable for the loss o Case 2 Darryl’s negligence was a but-for cause, but so is Donald’s. Both are liable for the loss. o Case 3 Neither Donna’s negligence nor Darryl’s negligence were but-forcauses of the loss…but each of their conducts was an “independently sufficient cause.” Both are liable. Without the independently sufficient cause analysis, the will lose under but for causation BUT FOR causation does not apply o Case 4 Doris’ negligence was not a but-for cause. A difficult question. See Res. 3d Torts §23 (J&G at 370) o 9. What is the rule of law from Matsuyama v. Birnbaum? Does a plaintiff whose chance of survival has probably declined from 20% to 10% as a result of a doctor's negligence, but who has not yet died, have a cause of action? o The court recognized the loss-of-a-chance doctrine in a case where medical malpractice deprived the of a less0than-even chance of surviving cancer. o The court found that medical science now makes it possible to estimate a patients probability of survival with reasonable certainty and therefore recovery for the lost opportunity of curing a disease was particularly appropriate. To hold otherwise, the court found, would undercut the deterrence principle by insulating whole areas of medical malpractice from liability and would force “the party who is the least bapable of preventing the harm (the patient) to bear the consequences of the more capable party’s negligence 9the doctory) o LOSS OF CHANCE DOCTRINE This doctrine allows a to recover damages by showing that The s negligence diminished likelihood of achieving a more favorable outcome (Massachusetts), or The was a substantial factor in causing the to lose a significant chance of escaping the harm in question… o What is the “multiple fault and alternative liability” rule that come out of Summers v. Tice? Why is such a departure from the general rule fair? Why is such a departure from the general rule fair? o 3 reasons to shift Each is shown to have acted tortiously, Actual wrongdoer is one of the small number of s before the court, and o Nature of the accident makes it impossible for to prove causation o The burden of proof on the issue of causation should be shifted to the s It shifts because only one of several s are at fault If can show that one of them acted negligently, the burden shifts to to show that they were not negligent. Multiple Fault and Alternative Liability o The burden of proof on factual… o 10. What is the rule that comes out of Sindell v. Abbott Laboratories? o Novel Doctrine of “market-share liability” which shifted to the s the burden of disproving factual causation, the court held that the ’s complaint state a cause of action Other doctrines (in particular, alternative liability and enterprise liability) were inapplicable of resolving the dilemma Alternative liability- only five of nearly two hundred manufacturers of DES were before the court Enterprise liability- if failed to show that it could not have produced the particular dosages consumed by the ’s mother, it would be liable only for that proportion of the judgment equivalent to that ’s share of the overall DES market (not liable for the full judgment, as in Ybarra and Summers). P.119 Sindell v. Abbott Laboratories PH: o Trial Ct. dismissed the action. Reversed. o Defendant’s Argument: It is impossible to determine which company produced the DES which caused the injury to PL, and PL failed to name all possible DES. FACTS: o While the PL’s mother was pregnant with her, she was given a synthetic estrogen, DES, to prevent miscarriage. Pl alleges that she developed cancer as a result of this action, and named five manufacturers of DES as co-defendants. There are 195 other manufacturers of DES [diethylstilbestrol]. ISSUE: o Whether the named s represent a substantial share of manufacturers of DES, and thereby the parties which caused the harm? Yes. STAT o 1) Duty, 2) Breach of Duty 3) causation, and 4) damages. The causation element requires proof of both cause in fact and proximate cause. REAS o If all the s jointly controlled the risk of harm, and the pl could establish by a preponderance of the evidence that the product was manufactured by one defendant, the burden of proof as to causation would shift to all dfs, so long as it only applies to a small unit of producers. Where in this case there are some 200 manufacturers this doctrine does not apply. o In determining causation, measure the likelihood that nay of the dfs supplied the product, by the percentage of DES sold by each of them for the purpose of preventing miscarriages. PL asserts that 5 or 6 companies produces 90 % of the DES marketed. Each manufacturer’s liability for an injury would be approximately equivalent to the damages caused by the DES it manufactured. o Plaintiff’s Argument: Pl was injured by a drug that was manufactured where 5 or 6 companies produce 90 % of the DES marketed o 11. Was there any question as to whether the defendants in Sindell were negligent? o o 12. Does the scenario in Sindell fit within the rule from Ybarra? Does it fit within the rule of Summers v. Tice? o 13. Do the facts in Sindell make out a case for enterprise liability? o 14. How does the "New York version" of market share liability in Hymowitz differ from the "California version" in Sindell? o 15. What is the best reason for using a national market in market share liability cases? What is the greatest weakness in using a national market approach?