Review of Native Vegetation Framework submission 075

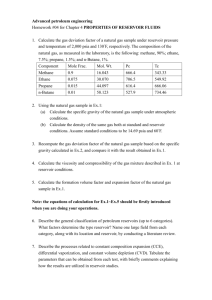

advertisement

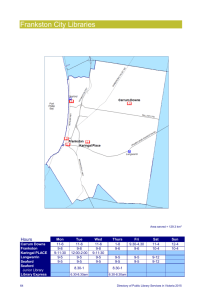

AUSTRALIA’S NATIVE VEGETATION FRAMEWORK CONSULTATION DRAFT SUBMISSION 31 MARCH 2010 Contact Details: Friends of Frankston Reservoir Inc. PO Box 5030, Frankston South, Victoria, 3199 email: friendsoffrankstonreservoir@yahoo.com.au website: www.friendsoffrankston.webs.com CONTENTS 1.0 Introduction ………………………………………………………………….............................2 2.0 Frankston Reservoir………………………………………………………. ...........................2 2.1 Natural Values........................................................................................................4 2.2 Cultural Values.......................................................................................................5 2.3 Regional Context....................................................................................................5 2.4 Reserve Designation..............................................................................................6 3.0 Melbourne’s Liveability and Natural Values………………………………………………......6 4.0 Management of Land…………………………………………………………..........................8 5.0 Native Vegetation Regulation…………………………………………………………...........11 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1. The Friends of Frankston Reservoir Inc. welcome the commitment of the Natural Resource Management Ministerial Council (NRMMC) to guide the ecologically sustainable management of Australia’s native vegetation for ecosystem resilience and the opportunity to make a submission. 2. The Friends of Frankston Reservoir Incorporated (FOFR) was formed in March 2006, as a result of the Victorian Government’s decision to decommission Frankston Reservoir, to give the Frankston community a voice in the future of the public asset which is Frankston Reservoir and to give the community a means by which they can contribute to the maintenance of the site as a public asset for the purpose of conservation. 3. FOFR are committed to ensuring that the Frankston Reservoir be established and maintained as a conservation reserve and that the surrounding catchment areas be conserved to meet this aim. A Frankston Reservoir Landcare group has been established under our auspices. 4. Australia has a growing population and particularly in Victoria, areas of open space are disappearing rapidly. With this decline, indigenous Flora and Fauna is also continuing to be increasingly threatened. FOFR believe it is their duty and responsibility to ensure the preservation of the Frankston Reservoir for future generations. It would be irresponsible to do the contrary. 5. Reflecting our interest and expertise, our submission centres on the Frankston Reservoir and the possible ecological linkages for this area of remnant native vegetation. 6. Friends of Frankston Reservoir broadly support and endorse the Consultation Draft paper. We focus on identifying those areas, where we believe the most impact will be felt in maintaining native vegetation. 2.0 FRANKSTON RESERVOIR 7. The Frankston Reservoir was constructed in 1920 by the State Rivers and Water Supply Commission. Since this time, the Frankston Reservoir and surrounding land has been managed and operated as an open storage reservoir, which has been securely fenced with public access prohibited to protect the quality of the water. Since its construction in 1920, Frankston Reservoir has had a variety of Statutory Authorities as Managers. It was last managed as a water catchment, by Melbourne Water. 8. Open storage reservoirs are being progressively replaced by Melbourne Water within the metropolitan region with enclosed tanks to protect water quality. Melbourne Water elected to construct an enclosed tank at the Frankston Reservoir site and therefore much of the 98 hectares and water body of the Frankston Reservoir was no longer required, for the protection of water quality. 9. In November 2005 the then Minister for the Environment and Minister for Water, Mr. John Thwaites MP, established a working group to advise as to the values of the area and the options for the establishment of a park at this site. The Working Group Terms of Reference were as follows: The Frankston Reservoir Working Group is convened to undertake a study of the Frankston Reservoir Site, an area of about 98 hectares owned by the Melbourne Water Corporation. The purpose of the study is to provide advice relevant to the future uses of the land within the Reservoir site including: a) The relative values of the site and their distribution within the site, with particular reference to ecological, natural, landscape or cultural interest or significance, and geological or geomorphological significance. b) Existing threats to natural and cultural values and public safety, including, but not limited to, pest plants and animals, inappropriate hydrological and fire regimes, wildfire, changed access arrangements and dangerous structures or features c) The nature and range of activities that should be provided for in a Frankston Reservoir Park and the assemblage of facilities that should be provided to accommodate such activities, having regard to its identified conservation values. d) The possible costs of establishing and managing the site as a conservation park e) The options for management of a conservation park comprising most or all of the site1. 10. The site of the reservoir is 98 hectares in total, of which 10 hectares comprises the reservoir, with the remainder of the site densely vegetated. The southern extremity of the site is 120 metres above sea level and affords views across the water body, Frankston, Port Phillip Bay, Melbourne CBD and 1 Frankston Reservoir Working Group, Frankston Reservoir Working Group Report, The Victorian Government Department of Sustainability and Environment, Melbourne, August, 2006, pages 2-3 across Mount Macedon. Frankston Reservoir is completely encircled by residential properties, with more than 200 homes directly bordering the Reservoir site. 11. Although the State Government Working Group process was completed in August 2006, no management authority has been appointed for the Frankston Reservoir as yet. The area has been reserved as a Natural Features Reserve pursuant to s.4(1)(m) of the Crown Land Reserves Act (Vic) 1978, although FOFR believe that the area would more appropriately be designated as a Nature Conservation Reserve the same as the decommissioned Beaconsfield Reservoir is designated. 2.1 NATURAL VALUES 12. Frankston Reservoir is a significant area of native vegetation and fauna habitat. The site supports state and regionally significant flora and fauna species, plant communities and fauna habitats. The site boasts 6 ecological vegetation classes (EVCs) of State significance2, so designated as a result of the high and very high depletion of similar vegetation classes throughout the state. 13. The most extensive of the EVCs, Grassy Woodland, is considered as endangered in the Gippsland Plain Bioregion and the Frankston Reservoir supports the largest stand of Grassy Woodland in the southern metropolitan area and the Mornington Peninsula and represents 16% of Grassy Woodland on all public land within Victoria3. Grassy Woodland is one of the most species rich ecosystems in temperate Australia, and in the temperate world generally and is particularly rich in native grasses, orchids and lilies4. 14. It is likely that the nationally threatened Growling Grass Frog occurs at the Frankston Reservoir. The site is an example of good habitat required for the survival of many amphibious creatures. It is vitally important that the water in the reservoir be treated to ensure that refuse from suburban streets does not contaminate the millions of litres of water within the reservoir and destroy the home of these rare and endangered species. 15. One of the Working Group report’s key recommendations was that “Native wildlife and vegetation on site should be protected under any future management regime”5. And further, we have been informed in writing that “It is vital that we save this asset for the community, because it contains some very special plants and animals – some of which are endangered”6 and “This 2 Practical Ecology, Flora and Fauna of Frankston Reservoir Report, April 2008, p.36 Ibid, p.36 4 J. Yugovic, Flora Assessments of Proposed tank sites Frankston Reservoir, Victoria. Report prepared for Gutteridge, Haskins and Davey Pty. Ltd., 2001, Biosis Research Pty Ltd, p.9 5 Frankston Reservoir Working Group, Op cit, p. 21 6 Dr. Alistair Harkness MP, Member for Frankston, letter to community members dated 12 February 2008 3 site contains some very special species of flora and fauna and is valued highly by the community as open space”7. 16. FOFR believe that preserving the Frankston Reservoir site as a dedicated conservation reserve, is the only means by which the biodiversity of the area can be preserved for the benefit of future generations. 2.2 CULTURAL VALUES 17. Aboriginal people have lived in Victoria for tens of thousands of years. Evidence of this occupation is present throughout the landscape in the form of Aboriginal cultural heritage places and in the personal, family and community histories of Aboriginal people. The Frankston Reservoir lies within the traditional lands of the Boonerwrung people and provides a strong link with Boonerwrung culture and economy. The intact bushland is much more representative of the pre-European landscape than most other areas in Boonerwrung country are at present. 18. There is a high probability that Indigenous Artefacts exist within the site, but remain undetected due to the dense vegetation within the site. 19. In the planning for the future of the reserve, FOFR believe that there must be consultation with representatives of the Traditional Land Owners of this area. It should be a priority of park planning that the Traditional Land Owners be included in the process. FOFR note that outside of the Working Group process, which concluded in August 2006, this has not occurred. 2.3 REGIONAL CONTEXT 20. Within the City of Frankston there are many large recreational spaces for community enjoyment, including Ballam Park, Overport Park and Baxter Park. In addition, there are some 60 other open spaces with playgrounds and barbecue facilities across the municipality. Port Phillip Bay and Kananook Creek provide for many water borne activities. 21. Sweetwater Creek Reserve is approximately 10 hectares in size and extends from Frankston Reservoir to Port Phillip Bay. The water from the Reservoir feeds Sweetwater Creek, so it is imperative that the water leaving the reservoir maintains a high quality for the flora and fauna which relies upon this water downstream. 22. Two other reserves within the municipality are managed by Parks Victoria, namely the Pines Flora and Fauna Reserve and Langwarrin Flora and Fauna Reserve. These reserves are managed for the purposes of conservation. 7 Mr. John Thwaites, Former Minister for the Environment and Water, Frankston News, 1st Quarter 2006 "Frankston Reservoir is smaller than Langwarrin and the Pines Flora and Fauna Reserve but the significance and quality of the vegetation is similar in all 3 reserves."8 The Frankston Reservoir is unique in that it has a water body, which creates a larger diversity of EVC’s. If appropriately managed for the purposes of conservation it is highly likely that the diversity of flora and fauna within the Frankston Reservoir will increase9. 2.4 RESERVE DESIGNATION 23. FOFR supports the upgrading of the designation of the Frankston Reservoir to that of a Nature Conservation Reserve under s.4(1)(o) of the Crown Land Reserves Act (Vic) 1978, to preserve the remaining native species inhabiting Frankston Reservoir and to protect the biodiversity of the area. 24. The current Natural Features designation allows for “controlled low-intensity exploitation of natural resources”. This means that environmentally sensitive areas are susceptible to destruction, direct destruction by park planners and indirect destruction through park planning which enables park users to encroach upon environmentally sensitive areas. 25. The Land Conservation Council’s, Final Recommendations for Melbourne Area District 2 Review 1994, made provision for the designation of Natural Features Reserves in Chapter G. It appears that two principles underlie all of the elements (emphases added): ‘While these areas are not recommended primarily for conservation of significant native species, they are important because (along with road reserves) they often provide the only suitable habitat for the many common and uncommon species that either still use, or were once widespread in, those land types that have been largely cleared.’ ‘They also make various contributions to our well-being, when used for recreation, relaxation, scenic landscape appreciation, education and protection against land degradation.’ 26. Frankston Reservoir has acquired a quite special conservation value due to the exclusion of human activities for the past nine decades. This situation presents a compelling argument to demand a classification of its own. 3.0 MELBOURNE’S LIVEABILITY AND NATURAL VALUES 27. Public open space is an important community asset and contributes significantly to the liveability of a city. Melbourne is frequently referred to as one of the world’s most liveable cities and the Victorian Government actively promotes Victoria as ‘a great place to live, work and raise a family’. This liveability however is threatened by the diminishing of open space and the culture of consumption resulting in environmental degradation. 8 9 Practical Ecology, Flora and Fauna of Frankston Reservoir Report, April 2008, p.39 Ibid, p.39 28. The recently completed State of the Environment Report by the Commissioner for Environmental Sustainability found that Victoria is the most cleared and most densely populated State within Australia10. More than half of Victoria is already cleared and of the native vegetation remaining, there is continuing loss at the rate of 4,000 hectares per year, mostly at the expense of already endangered grasslands11. The need to actively encourage the preservation of native vegetation is glaringly apparent when our State has the highest proportion of subregions, 48%, in poor condition12. 29. Human activity continues to cause declines in flora and fauna condition. Population growth, urbanisation and consumption are continuing to the detriment of our environment. Current thinking is to exploit resources leading to a complete use of all land and resources without consideration of the impact of such uses on the land. 30. It is well documented that biodiversity is critical to overall environmental health. “Losing biodiversity or 'species richness' makes environments vulnerable and less able to cope with existing and future pressures”13. In Victoria it is well documented that 157 species of native animals and 778 species of native plants are rare or threatened with extinction. Already in Victoria, 51 native plant species and 24 animal species have become extinct14. The State of the Environment Report highlights that “[t]he Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988 is failing to meet its stated objectives and needs to be reviewed to address Victoria's natural environments and their vulnerabilities to climate change. It also needs an adequate long-term allocation of resources to ensure effective achievement of its objectives”15. 31. Through conservation of areas specifically for the purposes of preservation of biodiversity and the processes essential for human survival, the community benefits. The Victorian Government’s Land and Biodiversity at a Time of Climate Change: Green Paper (hereinafter referred to as “the Green Paper”) recognises the importance of education and behaviour change in meeting the challenges of biodiversity and of maintaining our land, citing multiple benefits including “cost-effective means of achieving environmental outcomes, while playing an important role in building social and human capital, and supporting communities to adapt to change”16. Frankston Reservoir represents an opportunity for use as an educational tool, particularly in biodiversity programs. The Green Paper asserts the need to investigate new directions for educational and behaviour change programs, which place “a greater 10 Commissioner for Environmental Sustainability Victoria, State of the Environment Report 2008: Summary, p.12 11 Commissioner for Environmental Sustainability Victoria, op cit, p.12 12 Ibid, p.12 13 Ibid, p.13 14 Ibid, p.13 15 Ibid, p.13 16 Victorian Government Department of Sustainability and Environment, Land and Biodiversity at a Time of Climate Change: Green Paper (2008), p.63 emphasis on climate change adaptation and resilience, the impact of recreation and biodiversity and broader awareness of the implications of consumer choice and everyday activities on the health of our ecosystems”17. 32. There are a large number of educational institutions within a short distance of Frankston Reservoir, including a campus of Monash University, which could utilise the reservoir for low impact supervised environmental activities within the area as a means to better engage young adults to “take personal responsibility for environmental management”18. 4.0 MANAGEMENT OF LAND 33. Over the past 200 years Australians have destroyed or degraded more than 75 per cent of the country’s native vegetation. Land management techniques are not changing swiftly enough to protect the remaining bush or its species and we are now suffering severely from the excesses of the past. For the benefit of future generations of Victorians it is essential that we conserve and preserve remaining remnant vegetation. Endangered and rare EVC’s are not only a legacy of the agricultural development of European settlement, but also an example of the loss which has continued in recent years. 34. The Green Paper has highlighted that the world is facing a biodiversity crisis19. “Despite improved understanding of environmental issues and the policies and initiatives implemented in recent decades, Victoria's land and biodiversity has continued to decline. Native vegetation is still experiencing net loss, weeds and pests continue to threaten environmental and agricultural values and nearly a third of our rivers are in poor or very poor condition. The situation will be exacerbated by the emergence of additional pressures associated with climate change. The scale of the challenge we face is immense and highlights the long-term commitment required to address it.”20 35. The long-term commitment required to address the loss of biodiversity will largely be dependent upon the role of the Victorian Government and its partner agencies in the management of public land. One third of Victoria comprises public land, however this figure is considerably smaller within Metropolitan Melbourne. One of the Green Paper’s intended outcomes is to maintain the ecological integrity of land so it continues providing public good services. To achieve this the Green Paper further provides for “ongoing public land management which [involves] reducing threats (through activities such as weed and pest removal, erosion control and ecologically appropriate fire management), rehabilitating degraded land and ensuring land is used appropriately so it continues providing ecosystem services”.21 17 Ibid, p.64 Victorian Government Department of Sustainability and Environment, op cit, p.63 19 Ibid, p.3 20 Ibid, p.12 21 Ibid, p.25 18 36. FOFR believe there has been an unnecessary desire in recent times to create recreational outcomes for Open Space. Public open space is an important community asset and contributes significantly to the liveability of a city and provides many opportunities for communities. Management of land, however, should involve the best possible outcomes for the landscape. That is land should be managed in the best interests of the land, rather than for what can be reaped from the land by Victorians. If a site exhibits high conservational significance, these conservation values should be protected and enhanced, without consideration of recreational potential. 37. The proposed 50 year vision for land and biodiversity in Victoria is, “Victorians actively conserving and restoring ecosystems to ensure our land, seas and waterways are healthy, resilient and productive”22. A natural progression from this is that areas such as the Frankston Reservoir be conserved and restored to meet this vision. The Green Paper further submits that “Parks and forests will provide some of our best opportunities to respond to the threats posed to natural systems by climate change”23. 38. The need to protect and conserve the Frankston Reservoir becomes increasingly apparent as the population growth and expansion in Frankston and the Mornington Peninsula continues to encroach upon open spaces within the region. The Frankston Reservoir provides an opportunity to protect flora and fauna species; develop captive release programs; conduct further studies and research; and opportunities to raise awareness of the values of the site through community engagement activities and educational activities. The Frankston Reservoir could also play a role in Biolinks, by providing an opportunity to restore ecological connectivity within human modified habitats. 39. In most metropolitan parks, conservation is treated as having a low priority, and intensive human activities are dominant. In contrast, conservation is the dominant objective for National parks and conservation reserves, which are generally considerably larger than 98 hectares and necessary infrastructure can be hidden unobtrusively. The existing area of the Frankston Reservoir is so precious that people-intensive activities and infrastructure on the site would be counterproductive to the main conservation objective. 40. Public participation can improve planning and decision making in respect of land management and such participation reflects the public interest nature of land management and biodiversity conservation and is consistent with Victoria’s Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities, which recognises the legal right to “take part in public affairs”. 22 23 Victorian Government Department of Sustainability and Environment, op cit, p.30 Ibid, p.52 41. Statutory authorities including Catchment Management Authorities, Parks Victoria, Coastal Boards and Water Boards as well as local governments contribute to strategic planning and implementation of a number of natural resource management programs, however, community groups, landholders and volunteer organisations have a critical role in articulating local priorities and are often the primary agents for on-ground implementation. The contributions of local volunteers in relation to maintenance activities at Frankston Reservoir have been enunciated in both the State Government’s Working Group Report24 and the Frankston City Council’s draft plan25. This emphasises the absolute necessity for community engagement in planning and recurrent resource capacity. In the pursuit of ongoing funding, care should be taken to avoid exclusion of community, which could be the result of any potential land transfers required as a result of potential Caring for our Country land management funding criteria. 42. It has been observed that bushfires will occur more frequently and severely as a result of climate change. “The number of very high or extreme fire danger days across south-eastern Australia is expected to increase by up to 25% by 2020 and up to 230% by 2050”26. The recent bushfires in Victoria highlight the importance of appropriately managing the risk of fire, for both preservation of human health and property and preservation of biodiversity and conservation. The urban setting of the Frankston Reservoir highlights the importance of management requirements. An accidentally lit fire in 2003 was able to be controlled within the reservoir by the Country Fire Authority (CFA), although a significant portion of the vegetation was burned. This exemplifies the need to control and supervise access to the area as one element of risk management. Of considerable concern is the failure of Frankston Council in the development of their plan for the area to include the CFA recommendations, instead branding the measures as “over the top”. 43. The Green Paper discusses the need to prevent negative off site impacts at the boundaries between private and public land. “[T]he boundary between public and private land is often a place of conflict. Just as private landholders are required under the Catchment and Land Protection Act 1994 to avoid offsite impacts of their land management actions, the government has a responsibility to limit the spread of weeds, pests and fire from public to private land”27. 44. There exists the potential for ecological linkages and wildlife corridors between the Frankston Reservoir and other areas of open space such as Sweetwater Creek and Tangenong Creek, which are directly aligned with 24 Frankston Reservoir Working Group, op cit, p.33 Aspect Studios, Frankston Reservoir Master Plan Discussion Paper, completed for Frankston City Council, 19 May 2008, at 7.4, p.68 26 Commissioner for Environmental Sustainability, op cit, p.14 27 Victorian Government Department of Sustainability and Environment, op cit, p.25 25 Frankston Reservoir. Further linkages are possible extending through Baden Powell and Paratea reserves and through Mount Eliza, including Moorooduc Quarry. 45. Although there are significant conservation areas east of the Moorooduc Highway, such as the Langwarrin Flora and Fauna reserve, due to the presence of the Moorooduc Highway, there are limited opportunities for creation of any wildlife corridor in that direction. 5.0 NATIVE VEGETATION REGULATION 46. FOFR believe that there are significant deficiencies in the implementation of native vegetation regulation, which undermine our ability to maintain native vegetation. Native vegetation contributes to carbon sequestration, biodiversity conservation, water quality management as well as many other ecosystem services, for the betterment of all Victorians. 47. The Policy Document Growing Victoria Together: Innovative State. Caring Communities, describes priority actions with respect to “Protecting the environment for future generations” as “increasing and providing greater protection for areas of high conservation value”28. The Frankston Reservoir represents an area of great conservation value. 48. There is scientific consensus that climate change will significantly impact upon our environment, but whilst climate change offers a new challenge for Victorians and the liveability of our city, the current state of our environment, and the issues of unsustainable land use and perilous state of our biodiversity, are also the legacy of past practices and more recent failures to address these past practices. Unless we address native vegetation regulation we will continue to observe loss of native vegetation extent and condition and the fragmentation of habitat. 49. FOFR believe there is need for independent oversight of the implementation of the effectiveness of land management and biodiversity conservation policy in Crown and public authority land. There is a need for greater enforcement of native vegetation retention controls and threats management, which requires more monitoring and auditing of land and activities. We need to maintain Victoria’s natural assets, including plants and animals found nowhere else in the world. The threat is well documented and real. Human activity is impacting upon the environment like nothing before it. 50. The implementation of Victoria’s Native Vegetation, A Framework for Action, has led to some significant advances, such as: - The development of management and assessment tools in the form of systems of bioregional classification and EVC’s; 28 Growing Victoria Together: Innovative State, Caring Communities, policy document, p.25 - Recognition of the importance of not only vegetation extent, but also vegetation condition; A framework for the assessment of conservation significance and determination of regulatory responses on the basis of this assessment; A system of offsetting which, has the potential to provide some disincentive to clearing at the outset and can assist to provide some mitigation should clearing be permitted. 51. There are however significant deficiencies in implementation which undermine the “net gain” objective. Lack of monitoring and enforcement has resulted in the cessation of net gain offset works within the Frankston Reservoir. Despite an agreement by Melbourne Water, to offset removal of native vegetation for a period of 10 years, approximately four years ago, it has emerged that these works were ceased in early 2008 only a few years after their commitment. 52. The goals set out by the framework are laudable, however will not be achieved unless the mindsets of Government’s are altered to consider the importance of native vegetation intrinsically. Unless the land is managed in its best interests, the goal of conservation and maintenance of native vegetation will be lost. It is too common that the land is used for the purposes of human benefit. For example, practices involving recreational outcomes, exploit native vegetation for human interest. Only when human activity and use is not the driving factor in determining land management techniques will there be genuine protection for Australia’s native vegetation.