Cleft Secondary Deformities

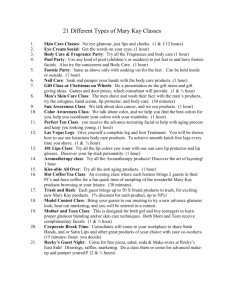

advertisement

SECONDARY CLEFT LIP DEFORMITIES Most children with clefts require a 2nd operation. Often the second operation is more challenging than the first. The frequency and severity of second operations have diminished because of: 1. overall improvements in cleft care 2. cleft care teams in specialised centres 3. presurgical orthopaedics 4. nasal correction at the time of primary surgery 5. the use of nasal moulding. APPROACH 1. Determine which structures are anatomically normally and which are not. 2. Look at the lip nose facial bones 3. Determine why abnormal structures are are abnormal: 1. uncorrected primary deformity 2. recurrence after surgery 3. iatrogenic. 4. Then, determine: 1. Realistic surgical goals, and 2. Optimal timing of surgery. RESIDUAL LIP DEFORMITIES A. UNSATISFACTORY SCARS B. ABNORMAL APPEARING REGIONAL ANATOMY 1. Tissue deficiencies 2. Anomalies of the lip landmarks 3. Vermilion shortage or malalignment 4. Buccal sulcus anomalies 5. Orbicularis malposition or diastasis UNILATERAL LIP DEFORMITIES 1. Unsatisfactory scars The first scar is the best. Often due to technical issues - poor handling of the tissues, closure under tension, use of large sutures tightly tied, and sutures being left in place for too long. Millard urges restraint in scar revision between the ages of 8 and 18 years. Revision techniques: 1. straight line 2. wave line 3. z-plasty 4. w-plasty 5. stair-step 6. Microhair transplantation can also be considered in men to camouflage hair-bearing lip scars These can be used to: 1. re-orientate landmarks 2. lengthen a tight upper lip 3. relax a notched vermilion 4. lift a drooping lateral lip Z Plasty For philtral column scar, only the epithelium is de-epithelialised to maintain bulk in this vest over pants closure 2. Discrepancies in quantity 1. Vertical maldistribution: Short or long lip 2. Horizontal maldistribution: Flat (tight) upper lip 3. Nostril sill / alar base deficiencies. Long lips: Typically with Tennison, Le Mesurier and triangular flap repairs. Correction o Full thickness excision from the upper part of the lip just below the nostril sill. o lip can be further shortened by excising any transverse scars across the philtrum and resecting a triangular composite from the floor of the nasal vestibule Short lips: Typically with straight line repairs (Rose-Thompson) and rotation-advancement. After a year, as the scars mature further, Millard repairs tend to attain normal length. Correction o If straight-line repair was previously performed and the deficiency is severe, then the cleft should be reopened and rotation advancement flap(s) used. o V-Y advancements emphasizing downward rotation of the medial segment o Other lengthening techniques are through-and-through Z-plasties, triangular flap transpositions along previous vertical scars Tight lip: Uncommon. Usually associated with early straight line or triangular flap repair. Correction: Abbe flap. 3. Missing or misplaced landmarks 1. Loss of philtral column effacement Correction of lost philtral definition is difficult; thus primary surgical repair is important. Options i. Subcutaneous rotation flaps ii. Onizuka ‘roll-over’ flap of muscle tissue out of the central dimple iii. Chondral or chondro-cutaneous grafts from the ear or nose. iv. Muscle splitting technique (see below) 2. Deformities of the Cupid’s bow: a) absence of peaks b) asymmetries of white roll Correction: white roll flap (A) small localised z-plasty(B), or free graft (C) 4. Vermilion deformities Lack of vermilion may cause o notching at the free vermilion border (whistling deformity) o deficiency of the central vermilion tubercle o deficiency of the lateral vermilion. If possible, during primary repair, vermilion should be preserved so that it can later be moved around as desired. Whistling deformity o Z-plasty, V-Y advancement and posterior mucosal transposition flaps can be used to move vermilion around. o Free tongue graft (from the lateral aspect of the tongue below the papillary line.) Lateral vermillion deficiencies o Major deficiencies of lateral vermilion can be corrected with a vermilion flap from the lower lip (Kawamoto.) o bipedicled lower to upper cross-lip visor flap to augment the upper lip vermilion. Requires 2 stages (Wagner) Central tubercle deficiencies o VY and Z plasties o Temporoparietal fascial graft for augmentation of the free border of the lip. o Buried tunnelled flap (Juri) 5. Buccal sulcus abnormalities The sulcus may be stuck down by adhesions or may be too shallow. It may be released by z-plasty, local mucosal flap, SSG, or free mucosal graft (A prosthetic device is usually needed for graft inset and take.) 6. Orbicularis oris derangement Muscle may be deficient, discontinuous or diastased. Problems usually occur when the muscle is not properly identified, repositioned or sutured at the time of primary repair. Results in unsightly bulging of the muscle on either side of the lip scar, depressions, and asymmetries that are further accentuated during animation and give the lip an unnatural look Correction: o Secondary identification, repositioning and suturing. o medial muscle is sutured in the midline of the lip, the oblique fibers are anchored to the periosteum of the nasal spine, and the lower fibers are directed into the pouting tubercle of the lip. o For small deformities, the lip scar can be excised, and the muscle fibers can be identified after undermining from their abnormal attachments and sutured together without tension. When a more significant deformity exists, such as the one seen in some bilateral repairs requiring skin and mucosal excision in addition to the muscle realignment and approximation, then a total lip repair should be planned, and all elements of the lip should be repositioned in the correct position. Special attention should be given to the width and length of the philtrum in rapport to the lateral lip segments BILATERAL LIP DEFORMITIES Most of the principles for unilateral lips apply to bilateral lips. 1. Scars Millard recommends: 1. Do one side at a time 2. Bank any excess tissue in case it is later needed for columella lengthening. 2. Discrepancies in quantity Correction of the tight lip (lack of horizontal length) is with an Abbe flap from the mid lower lip to the upper lip. Wide Lip The wide lip is due to a failure to reunite the muscle at the time of primary surgery and secondary correction thus aims to deal with skin and the muscle. Muscle should be completely released and reapproximated. Tight Lip Philtrum should be reconstructed with the following dimensions: o 0.8-1.2 cm wide at the vermilion border o 0.6-0.9 cm wide at the base of the columella o 1.7 cm high The common mistake made by many is fitting the Abbe flap to the apparent defect rather than reducing or rearranging the defect to philtrum dimension Z-plasties along the mucocutaneous junctions help prevent secondary notching of the vermilion margin. Pedicle can be divided at 2 weeks Millard reports survival of flap on mucosal bridge Short Lip VY and Z plasties are used but at the expense of width. Abbe is required when width cannot be sacrificed. 3. Missing or misplaced landmarks 4. Vermilion deficiencies interdigitate a denuded flap from the “excess” lateral vermilion tissue into the medial vermilion to minimize notching. Correction of large absolute tissue deficits in the central vermilion may necessitate the transfer of vermilion flaps from the lower lip. Holmstrom described a deepithelialized Abbe island flap that brings ample bulk and suitable lining for tubercle reconstruction and to help balance the lips. Alternatively, Guerrero-Santos suggests pedicled tongue flaps that are either transferred directly from the tip of the tongue or denuded and buried in the central upper vermilion. 5. Buccal sulcus abnormalities Because of their tendency to contract, mucosal transposition or advancement flaps should be designed with size and bulk to spare. combinations of Z-plasty and V-Y flaps supplemented with mucosal grafts on the denuded alveolar bone have been used 6. Muscle Deformities Treat same as for unilateral defects 7. Lower lip changes parallels the severity of the cleft and is particularly noticeable in patients with bilateral complete clefts. Changes include soft-tissue components that manifest as lower lip hypertrophy and ectropion with anterosuperior displacement of the soft-tissue points and inferolateral displacement of the oral commissure.