Oral History - Humanities and Social Studies Education (HSSE

advertisement

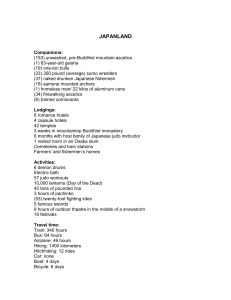

Title : Biography & History An Oral History Project on the Japanese Occupation By : Kwek Jin Foon Janet Programme : Advance Diploma in Primary Social Studies. Tutor : Dr Kevin Blackburn National Institute of Singapore 1 Nanyang Walk Singapore 637616 Date : 15 Oct 2002 My Dad’s life during the Japanese Occupation. The subject of my oral history interview is my father, Kwek Keng Tee, who was about 18 years old during the Japanese Occupation. The interview was done in Hainanese punctuated with the occasional Malay or English words when I was struck with a Hainanese vocabulary. Dad lived on a farm with his parents and his two younger brothers in Pasir Panjang area. Grandma managed the farm while grandpa ran a coffee-stall business near the beach opposite Tiger Balm Garden. As they were staying in Pasir Panjang, they experienced the beginning of the war. “(1 : pg 11)The Japanese had finally landed near the causeway, and there was fighting in Kranji and Mandai. Before long, it was Pasir Panjang, Bukit Timah and Yio Chu Kang.” He described the bomb shelter of those days as trenches covered with planks and soil at the top. They were deep enough for man to walk through upright. <Q2 & Q3. However, he could not recall the Malay Army Officer, LTA Adnan, who had fought bravely in Pasir Panjang as he claimed that they had already evacuated from the area.<Q19. Probably also, at that time, they were not able to read or had any radios. “(8 : pg 21) On 13 February, a battle between the British and the Japanese took place in Pasir Panjang. The Japanese attacked the British military stores there. The British troops, together with the Malay soldiers led by Lieutenant Adnan bin Saidi, fought bravely against the Japanese. (1: pg 6) From then on, we depended only on the newspaper for news. The radio was too expensive and hardly anyone owned one. “ It’s so sad to hear that they were left on their own to look for a safe place to stay and they had to stay in a pig sty at their first stop, Holland Road! Luckily, the shop owner at Tanglin/Orchard area was kind enough to take them in although they were not related. <Q4. At the Sook Ching operation, I am glad to know that although Dad is not highly educated, he was intelligent enough to listen to advises of others telling him to say the right thing when being ‘interviewed’. I have yet to find any historical link of Kampong Java as a screening area, but then it was a possible place.<Q6 & Q7. “(1 : pg 13)Orders were put out that all males above the age of 12 must be assembled at certain designated places. (1 : pg 16) There were other concentration areas set up in other parts of Singapore, for instance, in Jalan Besar, Tiong Bahru, Orchard Road and other places. (3 pg 7) It was only later that we found out that this was a mass screening exercise, a purging operation that was to be known as Sook Ching. The Sook Ching operation, which lasted for two months beginning in February, was but an early introduction to the arbitrary method of persecution by the Japanese Imperial Army and its officers.” At the screening, Dad had seen people being sent into different queues and never to be seen again. <Q7. “(1 : pg 17) Those suspected of being with the British Forces, auxiliary services like the MAS, ARP, the police Force or anything connected with the government, were taken away in the trucks waiting at each area. Most of these people were never seen alive again. --------- months later, it was discovered that those who did not return were shot at Ponggol, Changi Beach and other secret places.” The fact of innocent civilians being killed at beaches was evident when my dad mentioned seeing human skulls being washed up at Pasir Panjang Beach but he was not sure where they came from. <Q8. I wondered whether the skulls could have come from the sea off Sentosa as the island is quite near Pasir Panjang Beach. “(2 : pg 112) The prosecution said that massacres had taken place at the seaside at Ponggol, the seaside at the tenth mile on the Changi Road, and the sea off Pulau Belakang Mati (now called Sentosa). (2 : pg 114) Then another witness, a survivor of the massacre off Pulau Belakang Mati, gave evidence. He told the court that several hundreds Chinese were put into boats which were towed out to sea by a tug. Off the island, they were thrown into the sea and machine-gunned.” Dad also revealed how some people escaped death by pretending to be dead in trenches. <Q8. “ (5 : pg 262)…. a Chinese boy ….. stood behind a grown man, and the bullet from the Japanese rifle, passing through the heart of the man in front of him, went harmlessly over his shoulder. The weight of the corpse falling back pushed him into the grave . The Japanese soldiers shuffling through the mud thought he was already killed, and by some error did not completely fill the grave . As a result the boy could breathe, could still see a small patch of sky. All day, he laid under the weight of the dead man . When darkness came, he crawled out of the grave, along a monsoon drain ….. and eventually he reached the safety of a Chinese village, where he explained what had happened to him and was given food and shelter.” Surprisingly, my father liked the life he had during the Japanese Occupation. <Q9 & Q24. He actually mentioned it twice during the interview. He also managed to secure a job in a rubber factory managed by a Japanese Officer. <Q10 & Q11. Not only was he paid with a salary, but he was also able to receive rice more times than others. Firstly, as a Japanese staff, secondly, if he worked over-time and lastly, by using his identification card. Besides rice, he was rewarded occasionally with cigarettes and sugar. He did not have to eat tapioca like some others. <Q17. “(4 : pg 63) The value of my new job lay rather in the payment in kind that went with it – some 10 katis (about 15 pounds) of rice, sugar, oil and, most tradeable of all cigarettes. These rations were better than Japanese money, for as the months went by they would get scarcer and cost more and more in banana notes. (1 : pg 22) People working in the military or semi-government establishments like the wharf and shipyards got partly paid in rice. Others had to buy from black market or supplement with sweet potatoes or tapioca, if you could get your hands on any, because these too were rationed. (1 Pg 31) A job then was like a form of insurance to obtain some food.” Moreover, as a Japanese staff, he was given a special pass in a form of an arm band. Since no name of the owner was indicated on the arm band, my grandpa also made full use of it to go to town to buy necessities. <Q24. Other jobs got other forms of privileges. “(1 : pg 37) It was a clerical job and, being with the government, we were given better rations of rice and potatoes, and a big blue badge of office that was respected by shopkeepers when we are queuing for anything. At times, you could even jump queue. I wore the badge everywhere I went, and was even a bit proud of it.” Another surprising issue is that most of the Japanese soldiers encountered by my dad were actually Taiwanese. They spoke mandarin and Hokkien. <Q22 & Q23. “(1 : pg 16) At the table, one of the soldiers asked me, surprisingly in Hokkien, my name, age and occupation. “ When a colleague told me that Taiwan was once under the Japanese Rule, I decided to look up the history of Taiwan. Taiwan was under the Japanese Rule for 50 years, from 1895 to 1945. “(6 : pg 29) …Under the provisions of the 1895 Treaty of Shimonoseki that ended the war, China ceded Taiwan and the Pescadores to Japan “in perpetuity.”…. (6 : pg 33) Thus, in the fall of 1945, Taiwan was stripped from the Japanese empire and turned over to the Republic of China. (6 : pg 29)After China signed the Treaty of Shimonoseki, an official from Peking formally transferred control over Taiwan to Japanese authorities. (6 : pg 30) Tokyo’s first objectives after it “won” Taiwan via the Treaty of Shimonoseki were to establish order and domestic tranquillity and to promote economic development. Both, of cause, were seen as enhancing the power and prestige of Japan. (6 : pg 33) During the war, many Taiwanese volunteered for military service, and many more were inducted into the Japanese military. Their defection rate was low, and there was little protest against military service by the Chinese population of Taiwan. (4 : pg 78) In Taiwan – ruled by the Chinese, the Portuguese and the Dutch before the Japanese came – there was no hatred. Had the Japanese stayed on in Singapore and Malaya, they would, within 50 years, have forged a coterie of loyal supporters as they had successfully done in Taiwan. “ I was relieved to hear that my grandpa managed to escape death twice. First, for recovery from serious injuries sustained after being hit by a stray bomb. <Q14, Q15 & Q16. It was sad to hear that he was not sent to the hospital. As a young child, I have seen his crooked toe when he was alive but had never asked him about it. His release after being captured for selling “smuggled” goods was also a narrow escape. He could have been killed. <Q14. Dad’s witness of the Cantonese man hung to death for stealing bananas was scary. <Q21. However, this was necessary to maintain some law and order in Singapore at that time. “(1 : pg 23) When things ran short, stealing became a popular sport. The Japanese did try to maintain some semblance of law and order in the early stages. It seemed four persons were caught stealing or doing some other unapproved acts. Their heads were chopped off and displayed on stakes at the little park at the junction of Dhoby Ghaut and Bras Basah Road in front of Cathay Building. People flocked to see those heads, and stealing promptly became unpopular. (3 : pg 7) Heads displayed on poles in the city, tales and experiences of torture by the much-feared Kempeitai (Military Police)……. (4 : pg 60) The man had been beheaded because he had been caught looting, and anybody who disobeyed the law would be dealt with in the same way. (4 : pg 74) The Japanese Military Administration governed by spreading fear. It put up no pretence of civilised behaviour. Punishment was so severe that crime was very rare. In the midst of deprivation after the 2nd half of 1944, when the people half-starved, it was amazing how low the crime rate remained. People could leave their front doors open at night.” I feel proud of Dad when he mentioned that he would rather face punishment or even possible death rather than to get the man who spilled human waste at a sentry post into trouble. <Q20 & Q21. The slap he got must had been very hard to have made him go deaf in one ear. Getting slaps seemed to be one of the more merciful punishments melted out during the Occupation. “(1 : pg 34)One day, I broke a bracket that held the filter for the bouillon and Takemoto was not slow in delivering a right-fisted smack on my jaw. My molar was loosened and my lips cut. (1 : pg 36) One after another, we were given two whacks on the jaw by the officer – one on the left and one on the right, just to be even. This was done with the finger potion of the fists. If he had used his knuckles, we would have been out for days.” When I tried to find out whether the women were abused during the Occupation, I observed that Dad did not want to elaborate much on the subject. <Q18. Perhaps being a conservative man, he must have found it embarrassing to talk about such things to an opposite sex. Although ‘comfort houses’ were provided for the soldiers, sad to say that women did suffer. [(4 : pg 58 )Within 2 weeks of the Surrender, ………..I cycled past and saw long queues of Japanese soldiers snaking along Cairnhill Circle outside the fence. I heard from nearby residents that inside there were Japanese and Korean women who followed the army to service the soldiers before and after battle. …… there was a notice board with Chinese characters on it, which neighbours said referred to a “comfort house.”] Dad revealed ‘disturbances’ of women which was quite possible, maybe the comfort houses were not available at the beginning of the Occupation. [(4 : pg 59) Although rape did occur, it was mostly in the rural areas….. (7 : pg 34) One source mentioned that after the rape, the Japanese man shot the woman in the back as she tried to escape. Another Japanese war veteran recalled, “ Once I saw a woman’s corpse with a bamboo pole stuck into her genitals.”] Dad was not so happy when the Japanese surrendered as it meant losing his job with an income of salary and food. <Q24. He missed his Japanese superior at the Rubber Factory. <Q12. “ (2 : pg 122) After the surrender, Japanese soldiers were put on the labour force. They worked at Keppel Harbour, Bukit Timah and Paya Lebar Airport.” Fortunately, he had my grandparents’ farm and coffee stall business to fall on. To conclude: As time goes by, we will reach a day when it’s not possible to interview one who have had authentic experience of the war and Japanese Occupation. As the Japanese Occupation occurred more than 60 years ago and ‘perish’ with time, the timing of this assignment is perfect. before such people It gave me the opportunity to keep a record of what my father had to go through. My greatest regret is not being able to interview my grandparents. They must have had a different story to tell. Footnotes: 1. Escape from Battambang. A personal World War II Experience by Geoffrey Tan. 2. Syonan – My story. The Japananese Occupation of Singapore by Mamoru Shinozaki. 3. Beyond the Empires. Memories Retold by Cindy Chou. 4. The Singapore Story. Memoirs of Lee Kuan Yew. 5. SingaporeThe Battle That Changed the World. The enthralling story of the rise and fall of a magical city by James Leasor. 6. Taiwan (third Edition). Nation-State or Province? By John F. Cooper. 7. Living Hell. Story of a WWII Survivor at the Death Railway by Goh Chor Boon. 8. P4 Social Studies Textbook 4B. Discovering our world. The Dark Years by Curriculum Planning & Development Division, Ministry of Education, Singapore. Bibliography: 1. Cooper, John F. Taiwan (third Edition). Nation-State or Province? Westview Press, 1999. 2. Chou, Cindy. Beyond the Empires. Memories Retold by Cindy Chou. National Heritage Board, 1995. 3. Goh, Chor Boon. Living Hell. Story of a WWII Survivor at the Death Railway. Asiapac Books Pte Ltd, 1999. 4. Leasor, James. Singapore. The Battle That Changed the World. The enthralling story of the rise and fall of a magical city. House of Stratus, 2001. 5. Lee, Kuan Yew. The Singapore Story. Memoirs of Lee Kuan Yew. Times Editions Pte Ltd, 1998. 6. Shinozaki, Mamoru. Syonan – My story. The Japanese Occupation of Singapore. Times Books International, 1982. 7. Tan, Geoffrey. Escape from Battambang. A personal World War II Experience. Armour Publishing Pte Ltd. 2001. Reference: Curriculum Planning & Development Division, Ministry of Education, Singapore. Social Studies Textbook 4B : Discovering our world. The Dark Years, 1999. Oral History Transcript Life during the Japanese Occupation Q1. How did you know that the Japanese had invaded Singapore? We heard a siren. An aeroplane dropped a bomb at Pasir Panjang, near the Tiger Balm Garden beach. We ran to an underground bomb shelter. Q2. What was the shelter like in those days? It was a dug out tunnel covered with planks first, then soil and grass on top. Q3. Who dug the tunnel? Could it hold many people and how deep was it? The British. It was very long, from one hill to another hill, head high; we could walk through. Not sure how many people could go in. Q4. Was it safe to stay in Pasir Panjang then? While the fights were going on, we were told to move away from the area. We packed some clothes and food and ran to Holland Road. We stayed in someone’s pig sty for 2 to 3 nights. Then we headed to Tanglin/Orchard area and stayed in a relative’s work place, a shop, for a few days till the surrender on Chinese New Year day. Pg 1 Q5. How did you know about the surrender? There was a siren. The British Flag was replaced with the Japanese Flag in Tanglin area. Q6. What happened after the surrender? We walked all the way back to Pasir Panjang. There was no water to drink. It was a very long walk. One day, everyone had to go the Kampong Java to be screened and interviewed. Better not say that you are studying or working with the British. Could be captured and be killed. Q7. How did you know not to say these? Those who went before us came back and warned us. Those who said that they were studying, were asked to walk in a line and those who were working for the British, walked on another line. They never came back. Some were sent to Thailand or Malaya to dig tunnels or make roads. Many died of swollen feet, illnesses and starvation. Q8. Were there any killings in Singapore? I heard about those who were killed by firing . Some fell into the trenches and pretended to be dead. They crawled out and escaped in the middle of the night. Once while looking for herbs at the beach opposite Tiger Balm Garden to treat a relative who was suffering from ‘snake’ – shingles , I saw lots of human skulls being washed up to the beach. I quickly ran away. Pg 2 Q9. What was life like during the Japanese Occupation? I quite like life during the Japanese ‘Hand”. Q10. How was that so? A former Japanese Army Officer took over the management of a Rubber Factory in Pasir Panjang. I worked there as a ‘Mandur’ (supervisor in Malay). I was given free rice, food and a salary. Q11. What did the factory make? Were there many workers? We made tyre tubes. There were many pretty Teochew ladies working there. I worked there till the Japanese surrendered. Q12. What happen to your ‘Japanese Boss’ after the Japanese surrender? He cried and the British captured him to do odd job. Q13. Did you continue to work in the Rubber Factory? No, the British took over the factory and I went back to work in our farm. Q14. Did Grandpa continue with his coffee stall business during the Japanese Occupation? Yes, his stall was near the beach. One day, some Japanese soldiers, they were not real Japanese, they were recruited overseas Chinese, sold stolen sugar and cigarettes to your grandpa. After that, they sabotaged your grandpa by reporting to the Japanese officers. Pg 3 The officers went to the coffee stall to check for smuggled goods. Your grandpa was taken away and beaten on the shoulders with logs. He came back with swollen shoulders. He could have been killed by firing if the officers were nasty. Q15. How did grandpa got his big toe crooked? One day, your Grandpa, grandma and myself were standing near the Pasir Panjang hill where firing took place. A ‘bomb’ from a big gun exploded near us. Your Grandpa injured his thigh and toe. He was bleeding badly. Q16. Was he sent to hospital? No, there’s no money. He self medicated and bandaged the wounds himself. After a long time, he recovered. Q17. Did you all have enough food to eat during the Japanese Occupation? It wasn’t a problem. We had our own farm. We also got lots of rice because of me working for the Japanese and everytime I worked overtime, I received extra rice. I could also collect rice with my Identity Card. Pg 4 Q18. Were women ill-treated? The Japanese soldiers ‘disturb’ the women while their husbands were tied up. Young ladies had to hide in the ceilings of their houses to avoid being captured by the Japanese. Q19. Since you were staying in Pasir Panjang area, have you heard of a Singapore Malay Officer who fought bravely against the Japanese? No, we were told by the British government to leave the place. We went to Holland Road area. Q20. You once mentioned that a Japanese Soldier slapped you and caused your ear to go deaf. What happened? One day, the man who collects human waste in buckets accidentally spilled some shit at the entrance of a sentry post. People were asked who did it and I was one of those who refused to reveal the culprit So I was slapped very hard in the face. It was very painful. After that, I became partially deaf on the left ear. Q21. Why didn’t you reveal the culprit identity? The poor man could have been killed. They hung a Cantonese man who was doing building work for the Japanese by the neck till he died for stealing bananas from someone’s backyard. Pg 5 Q22. Do you hate the Japanese? No, they were not pure Japanese soldiers. Most of them were Taiwanese. Q23. How did you know that they were Taiwanese? They were speaking in Mandarin and Hokkien. Q24. Were you glad that the Japanese surrendered? I like those days during the Japanese Occupation. As a Japanese worker, I was also given an arm band for easy travelling. Your grandpa once used it to go to town by bicycle to buy provision as there was no name on the band. It was a great privilege. Thanks Dad, that was interesting. Pg 6