Chapter 4

advertisement

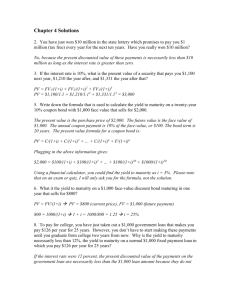

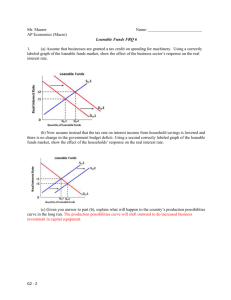

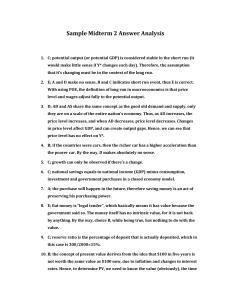

Chapter 4 Interest Rate Measurement and Behavior CHAPTER OUTLINE I II. Calculating Interest Rates A. Simple interest B. Compound interest C. Coupon rate on bonds D. Current yield E. Yield to maturity F. Zero-coupon bonds G. The inverse relationship between yields and bond prices H. Why long-term bonds are riskier than shorts I. Nominal versus real interest rates J. Return versus yield to maturity What Determines the Level of Interest Rates? A. Supply and demand determine the interest rate B. Why does the interest rate fluctuate? C. Behind supply and demand D. The importance of inflationary expectations E. Cyclical and long-term trends in interest rates CHAPTER SUMMARY This chapter focuses on how to calculate rates and how to analyze the factors that influence interest rates. Because money invested now can earn interest over time, a given amount of money received now is worth more than the same amount of money received later. Compound interest (interest paid on interest previously earned) further increases the value of money now relative to money later. Understanding this concept is the key to understanding one of the fundamental calculations used in financial economics--present-discounted value or, simply, present value. The yield to maturity of a security is that rate of discount that makes the present value of the securities income stream over its entire life equal to its purchase price. Many buyers, however, do not hold securities until they mature. For these buyers, the security’s annual rate of return is often a useful yardstick. The annual rate of return on a bond is defined as the change in the bond’s price over the year it was held plus its coupon payments as a fraction of the purchase price. The price at which the bond can be sold depends inversely on the market yields at the time of the sale. The present value formula shows why there is an inverse relationship between bond prices and bond yields. For any given set of coupon and face value payments offered by a bond, a lower yield (discount rate) will raise its present value (market price) and a 8 Chapter 4 Interest Rate Measurement and Behavior 9 higher yield will reduce its present value. In general, yields and rates of return in financial markets are quoted in nominal terms, which do not account for the effect of inflation. To determine a real rate of return, one must subtract that rate of inflation from the nominal rate of return. This will indicate the change in purchasing power earned by the lender. After discussing the calculation of interest rates, the chapter turns to an explanation of how these interest rates are determined. As interest rates represent the price of credit, they are determined by the supply of and demand for credit or loanable funds. Any factor that increases the demand for, or decreases the supply of, loanable funds at given interest rates will create an excess demand and cause the equilibrium interest rates to rise. Any factor that decreases the demand for, or increases the supply of, loanable funds at given interest rates will create an excess supply and cause the equilibrium interest rate to fall. TEACHING Interest rate calculations are the initial focus. Students with only a vague understanding of interest rate mechanics will benefit greatly from this material. The inverse relationship between bond prices and yields, a legendary source of student confusion, is explained, along with the notion of capital gains and losses. The key is to emphasize the fact that once the bond is issued the payment stream is fixed; so, a yield change entails a price change in the opposite direction. Although the mechanics of interest rate calculation are fairly straightforward, students must work problems to hammer it in. Such problems can be found in the Study Guide. Next comes the basics of interest rate determination. It is especially helpful for students with a weak or distant principles of economics background, but it may confuse students who were shown only the Keynesian approach via liquidity preference. Care should be taken to emphasize that interest rates are here being viewed as the cost of credit (rather than the Keynesian view of their being the opportunity cost of holding money) and, therefore, are determined by the supply of and demand for loanable funds. It is, of course, the same interest rate viewed from a different perspective. Useful Internet sites http://bobbyorr.gsia.cmu.edu/macro/notes/Yield1.html — Offers an example of calculating yield and present value. 2. http://www.fin.gc.ca/invest/bondprice-e.html — A more practical walk-through that accounts for the real features of the bond market such as semi-annual compounding. 1. 1. DISCUSSION QUESTIONS Is the risk of capital losses irrelevant if a person plans to hold a bond until maturity? Plans sometimes change, and even if they are not a holding a bond with lower rates than newly issued bonds, this risk is not appealing either. After all, a capital loss is simply the present value of all the future losses caused by being locked into a lower interest rate bond when higher interest rate bonds become available. 2. Why would anyone buy a bond that does not make interest payments? Capital gains generated by the low purchase price relative to face value. 3. If you expect interest rates to fall, should you buy long- or short-term bonds? Long, for a greater price appreciation (capital gain). 4. Interest rates were much higher in the late 1970s than the mid 1990s. Was credit more expensive back then? Yes, but not as much as it appears when you compare nominal interest rates. To get a true measure of the difference in the cost of credit, one must compare real interest rates (i.e., interest rates adjusted for inflation rates). 10 Ritter/Silber/Udell Money, Banking, and Financial Markets, Eleventh Edition 5. What would happen to the equilibrium level of interest rates if: A. borrowing for home building increased? B. a new highway program gets underway? C. foreign creditors lose confidence in the United States? D. the Fed raises reserve requirements? In all cases, interest rates rise ceteris paribus. ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS IN TEXT 1. The yield to maturity is higher because it takes account of the capital gain. The capital gain arises because the value at maturity (face value) exceeds the value (price) at purchase. 2. Zero-coupon bonds sell for less because they make no interest payments. The investor’s return is simply the difference between the price she paid and the price she gets for selling it or holding it to maturity (the face value). 3. Yes and no: bond prices and interest rates are inversely related due to the mathematics of the present value equation. However, the present value equation is the result of economic reasoning. If market interest rates rise relative to the interest rate on a bond I wish to sell, I will have to lower my bond’s price to raise its interest rate to a rate that is competitive with the rate on newly issued bonds. 4. The real interest rate reflects the gain in purchasing power with which savers are rewarded. It is a return that adjusts for the depreciation (or appreciation) of the purchasing power of a dollar that results from inflation (or deflation). 5. Falling interest rates mean capital gains for fixed-rate assets, larger gains for longer-maturity assets. 6. See the first two figures in the chapter. 7. The demand for loanable funds can cause the equilibrium interest rate to rise if business, government, or household borrowing increases. Increased profit expectations, increased government deficits, or expectations of higher consumer incomes will also raise interest rates, as well as reduction in the supply of loanable funds. 8. An increase in inflationary expectations shifts the demand for loanable funds to the right, as borrowers perceive a reduction in real rates, and the supply of loanable funds to the left, as lenders want to be compensated for inflation. 9. Interest rates tend to rise during cyclical expansions and fall during recessions, although this may be superimposed on a longer-term upward or downward trend in rates. The tendency for rates to rise during expansions results from the tendency of the demand for loanable funds to increase more than supply during such periods. 10. This is too broad a statement. There are many kinds of stock, many kinds of bonds, many kinds of risk, and many asset-holding strategies. 1. ESSAY QUESTIONS Assume a saver deposits $500 for two years in a bank account that pays 10 percent interest. What is the simple interest over two years? What would it be if the account were compounded annually? Why the difference? Simple interest is $ 100; with annual compounding it is $105 because interest is paid the second year on the first year’s interest. 2. Define the coupon rate on bonds. Is it a meaningful measure of the return on the bond? Is there a more accurate measure? The coupon rate is the bond’s coupon payment/face price. It is only an accurate measure of return if the bond’s price is very close to its face value. Yield to maturity is much more acceptable because it captures the capital gain or loss. Return also provides a more accurate measure. 3. “Returns were much higher in the 1970s than in the early-1990s because the interest rates were much higher.” True or false? Chapter 4 Interest Rate Measurement and Behavior 11 Though true for nominal returns, the statement is false, because it does not take into account the much higher inflation rates of the 1970s relative to the early-1990s. The real rates were actually quite similar in the two periods. 4. Using the loanable funds market diagram, demonstrate the effects of the following: A. a decrease in the saving rate; B. an increase in business investment spending; C. a reduction in the federal deficit; D. a rise in inflationary expectations. A. supply shifts left and the equilibrium rate rises; B. demand shifts right and the equilibrium rate rises; C. demand shifts left and the equilibrium rate falls; D. demand shifts right while supply shifts left and the equilibrium rate rises. 5. Explain the role of inflationary expectations, economic contraction and Fedral Reserve Policy in producing the record low interest rates observed at the end of 2002 and the begininng of 2003. Low inflationary expectations and economic contraction produced an inward shift of the demand curve for loanable funds. At the same time, Fed policy and low inflationary expectations worked to shift the suplly curve for loanable funds outward. Together these forces produced an excess supply of loanable funds and pressure for interest rates to fall.