Meth.instr. feeding of premature

advertisement

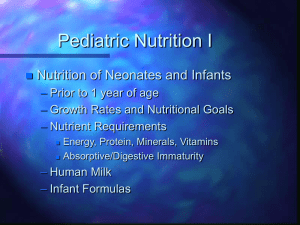

Methodical Recommendations for Students’ Self-work №__. Theme: Nutritional needs of preterm infants. Aim: To learn the peculiarities and special nutritional needs of preterm infants. Professional necessity of the theme: Prematurely born infants are of highrisk group, they have a greater than average chance of morbidity or mortality. So they need special care and medical supervising to help them to grow healthy. Nutrition is one of special and very important aspects of such care. Especially, because premature babies have immature digestive tract, which isn’t able to digest, sometimes, even breast milk. Technique of realization of practical Work 1. To know peculiarities of digestive tract of premature infants 2. To know transitional conditions of neonate period 3. To know peculiarities of physical and neurological examination of a newborn child 4. To know main rules and techniques of breast and formula feeding of infants Programme of student’s self-preparation. Gestational age, birth weight 1. First feeding of premature neonates in dependence on gestational age. Rules of feeding Time of first Volume of Type of food feeding Less than 34 weeks, less than 2 kg In 2 – 3 hours (!) after delivery 1 feeding First feeding – distilled water, second – 5 % glucose, others – breast milk* 2-4 ml Regimen of feeding 8-9 times per day More than In 2 – 3 hours 7 times 34 weeks, (!) Breast milk 5-7 ml per day more than 2 kg after delivery *breast milk can be given only in case if there is no regurgitation after intake of 5 % glucose 2. Requirements of premature infants. The energy expenditures for maintenance and the energy costs of growth are the determinants of the caloric requirements of the growing infant. The energy expenditure for growth includes both the energy value of the new tissue stores and the energy cost of the tissue synthesis. The estimated "basal" or maintenance metabolic rate of preterm infants, including an irreducible amount of physical activity, is lower in the first week after birth than later; and, in a thermoneutral environment, it is approximately 50 kcal/kg per day by 2 to 3 weeks of age. Each gram of weight gain, including the stored energy and the energy cost of synthesis, requires 5 to 6 kcal. Thus a daily weight gain of 15 gm/kg requires a caloric expenditure of approximately 75 kcal/kg above the 50 kcal/kg maintenance expenditure (See table 2.). There are individual variations among infants in activity, their ease of achievement of basal energy expenditure at ther-moneutrality, and the efficiency of their nutrient absorption. In practice, intake by the enteral route of approximately 120 kcal/kg per day enables most preterm infants to achieve satisfactory rates of growth. More calories may be given if growth is unsatisfactory at these intakes. Newborn infants who are growth retarded frequently require an increased energy intake for growth because of both higher maintenance needs and higher energy costs of new tissue synthesis. Table 2. Requirements of premature infants. Age Proteins (g/kg) Fats (g/kg) Carbohydrates (g/kg) Birth – 2 wks: 1-3 days 7 days 10-14 days 2 wks – 1 mo 2 mo After 2 mo 2-2.5 5.5 12-15 2.5-3.0 3.0-3.5 3.0-3.5 6.0 6.5 6.5 12-15 12-15 12-15 Kcal/kg 30-60 70 100-120 100-120 135-140 130 Caloric Density and Water Requirements The caloric density of both preterm and term human milk is about 67 kcal/dl at 21 days of lactation. Formulas of this caloric density have been used for feeding preterm infants. However, more concentrated milks, 81 kcal/dl (24 kcal/oz), are preferred by many when commercial infant formulas are used. The increased concentration allows feeding volumes to be smaller, an advantage when gastric capacity may be limited. The volume given when formulas of this concentration are fed at the rate of 120 kcal per kilogram per day, 150 ml per kilogram per day, provides sufficient water for most preterm infants for the excretion of protein metabolic products and electrolytes derived from the formula. However, if lower volumes of formula are given, insufficient water may be provided for renal excretion when relatively constant extrarenal losses occur. 3. Human milk and preterm infants. Preterm infants fed with their mother's milk have a more rapid rate of growth in weight, length, and head circumference, as well as a shorter time to regain birth weight, than those fed milk from the mothers of term infants. Pooled human milk from mothers of term infants does not meet all nutritional requirements of preterm infants and results in a slower rate of growth than is found with consumption of milk from mothers of preterm infants or commercial infant formulas. The low protein concentration of pooled, term human milk is probably the major cause of the poor growth; metabolic complications include hyponatremia at 4 to 5 weeks, hypoproteinemia at 8 to 12 weeks, and rickets at 4 to 5 months. Milk from mothers of preterm infants, especially during the first 2 weeks after delivery, contains more calories; higher concentrations of fat, protein, and sodium; but slightly lower concentrations of lactose, calcium, and phosphorus than milk from mothers of term infants. These differences in composition may be mainly a result of the lower daily volume of milk produced by the mothers of preterm compared to mothers of term infants. The higher fat content leads to the higher caloric density of preterm milk, which may be advantageous for the small infant with limited gastric capacity. The higher protein content of preterm milk is sufficient to meet the fetal growth requirement for nitrogen when the milk is consumed at 180 to 200 ml per kilogram per day. 4. Commercial Formulas for Preterm Infants Many results of studies on nutrient, electrolyte, mineral, and vitamin needs and tolerances of preterm infants, which were discussed earlier in this chapter, have been applied to the development of formulas specifically designed to meet the needs of small preterm infants. The common features of these commercial infant formulas are the use of whey-predominant proteins, carbohydrate mixtures of lactose and glucose polymers, and fat mixtures containing combinations of MCT and relatively unsaturated long-chain triglycerides. The formulas differ in content of sodium, calcium, phosphorus, vitamins, and minerals. Each of the special formulas has been shown to be associated with adequate growth and metabolic stability. PreHIPP PreNAN 5.Methods of Enteral Feeding The method of enteral feeding chosen for each infant should be based on gestational age, birth weight, clinical state, and experience of nursing personnel. Coordination of sucking, swallowing, and respiration appears at approximately 32 to 34 weeks' gestation. Preterm infants of this gestational age who are alert and vigorous may be fed by nipple. Infants who are less mature, are weak, or are critically ill will require alternate modes of feeding by vein or tube to avoid the risk of aspiration and to conserve energy. Gastric feeding of boluses of milk can lead to disturbances of respiratory function in infants with respiratory problems; thus, in some infants, continuous transpyloric feedings by nasal or oral tubes have become popular. Clinical results of this feeding mode have been excellent in many nurseries, but there have been some criticisms that bypassing the stomach and duodenum by ajejunal tube may cause inefficient utilization of the nutrients in the formula. Continuous gastric feedings may be tolerated by many small infants better than bolus gastric feedings, and they are satisfactory if gastric emptying is not limiting in the infant. Bolus feedings into the stomach via gavage tube or by nipple, every 2 to 3 hours, is the goal after the preterm infant shows a clearing of the respiratory distress and gastric emptying is not a problem. Whatever the mode of feeding, the formula volume should be advanced slowly - over at least 10 to 14 days in infants who weigh less than 1,000 gm and 6 to 8 days in infants who weigh more than 1,500 gm. 6. Parenteral Nutrition Parenteral administration of glucose, fat, and amino acids is frequently an essential part of the nutritional care of preterm infants, particularly those who weigh less than 1,500 gm. The high incidence of respiratory problems, limited gastric capacity, and intestinal hypomotility in small preterm infants dictates the need to advance the volume of enteral feedings slowly. The availability of parenteral nutrition components enables the supplementation of the slowly enlarging enteral feedings so the total daily intake by both routes meets the infant's nutrition needs. When required, full nutrition requirements can be met for considerable periods by the parenteral route alone. References 1. Committee on Nutrition: Nutritional needs of low-birth-weight infants. PEDIATRICS, 60:519, 1977. 2. Ziegler, E.E., Biga, R.L., and Fomon, S.J.: Nutritional requirements of the premature infant. In Suskind, R.M., ed.: Textbook of Pediatric Nutrition. New York: Raven Press, pp. 29-39, Textbook of Pediatric Nutrition. New York: Raven Press, pp. 29-39, 1981. 3. Reichman, B., Chessex, P., Putet, G., Verellen, G., Smith, J.M., Heim, T., and Swyer, P.R.: Diet, fat accretion, and growth in premature infants. New Engl. J. Med., 305:1495, 1981. 4. Gordon, H.H., Levine, S.Z., and McNamara, H.: Feeding of premature infants. A comparison of human and cow's milk. Amer. J. Dis. Child., 73:442, 1947. 5. Gaull, G.E., Rassin, D.K., Raiha, N.C.R., and Heinonen, K.: Milk protein quantity and quality in low-birth-weight infants. III. Effects on sulfur ammo acids in plasma and urine. J. Pediat, 90:348, 1977. 6. Raiha, N.C.R., Heinonen, K., Rassin, D.K., and Gaull, G.E.: Milk protein quantity and quality of low-birthweight infants. I. Metabolic responses and effects on growth. PEDIATRICS, 57:659, 1976. 7. Fomon, S.J., Ziegler, E.E., and Vazquez, H.D.: Human milk and the small premature infant. Amer. J. Dis. Child. 131:463, 1977.