Morality, Ethics, Deontology, and the Law…

advertisement

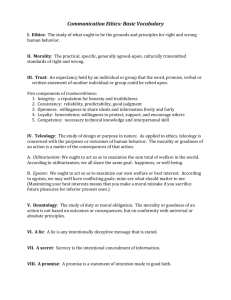

Morality, Ethics, Deontology, Law, and Enforcement: A Tentative Clarification Jacques Berleur University of Namur, Belgium International Federation for Information Processing IFIP-SIG9.2.2 Chair (Ethics of Computing) mailto:jberleur@info.fundp.ac.be When going through the literature about “ethics of computing”, we may be faced with terms that need to be specified. Is it a difference between morality and ethics? What is deontology? How are those terms related to the law? And finally how can morality, ethics, and deontology be enforced? Deontology Let us start with deontology. The definition given by the Robert & Collins dictionary is embarrassing: professional code of ethics! Moreover, the Cambridge Advanced Learner's Dictionary ignores our word, although the English Jeremy Bentham created it!1 But it has been re-imported in French, and includes an empirical study of different duties in specific professional fields.2 And even if we acknowledge that deontology is related to the profession, we must also admit that there are many words that are used. When analyzing the IFIP national societies codes, we found “code of conduct, code of ethics, guidelines, charter, code of fair information practices, code of professional conduct…3 What seems to be clearer is the recognized functions of those codes. J. Holvast mentions four of them: to make the professionals responsible, to supplement legal and political measures, to awaken the awareness of the public and to harmonize differences which can emerge between countries.4 M. Frankel enumerates five functions, two of them overlapping with the preceding ones: to help professionals to evaluate alternative courses of action and make more informed choices, to socialize the new professionals by sharing experience, knowledge and values, to monitor the profession by acting as a deterrent to unethical behaviour, to support professionals in resisting pressures from others - clients, employers, bureaucrats - and, finally, to help legislative, administrative and judicial bodies by serving as a basis for adjudicating disputes among members or between members and outsiders.5 These five functions are adapted from the eight he mentioned in a previous paper, where he had 1 2 3 4 5 Jeremy Bentham, (1748-1832), Deontology or the Science of Morality, work published in 1834, after his death. On Bentham, see also “The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy”, http://www.iep.utm.edu/b/bentham.htm#H6 André Lalande, Vocabulaire technique et critique de la Philosophie, Paris, Presses Universitaires de France, 1968. See the word “déontologie”, p. 216 Ethics of Computing: Codes, Spaces for Discussion and Law, Jacques Berleur & Klaus Brunnstein, Eds., A Handbook prepared by the IFIP Ethics Task Group, London: Chapman & Hall, 1996, 336 p., ISBN 0-41272620-3. (Available today by Springer Science & Business Media). Jan Holvast, Codes of ethics: Discussion paper, in Ethics of Computing: Codes, Spaces for Discussion and Law, Jacques Berleur & Klaus Brunnstein, op. cit., pp. 42-51. Mark S. Frankel, Professional Societies and Responsible Research Conduct, in: Responsible Science, Ensuring the Integrity of the Research Process, Vol. 2, National Academy Press, Washington, DC, 1993, pp. 26-49. 1 added some interesting features: to serve as a source of public evaluation, to enhance the profession’s reputation and the public trust, and to preserve entrenched professional biases.6 It appears clearly that there are functions that are oriented for the sake of the profession itself - the adherence to it, its identity, the assurance of competence, the way to regulate internal conflicts... But there are also functions which define the boundaries between the profession and the society: they allow the public to have a look at it, or the society to know what is happening in it; they act as an appeal for responsibility at different levels - firms, society, etc. In any case, deontology is related to a professional body, and to rules that govern it, and which come from the experience of the past as well as from the request of the present. But deontology is not only rules: it refers to values. We would suggest to qualify the used terms, code of ethics, or of conduct, by the word “professional”. Let us finally mention that the Council of Europe has tried, in the late ‘70s – early ‘80s, to elaborate a document on the ethics of data processing, but abandoned the idea preferring to suggest more legally constraining “Recommendations” in different sectors, such as police, social security, health, medicine.7 This raises the question of the link between deontology and the law. IFIP-SIG9.2.2 (Ethics of Computing) has recently published a Monograph for helping professional societies to discuss the form and the content of their deontological code.8 Ethics and morality Shall we dare to distinguish deontology and ethics where many organizations use both terms alternatively? Moreover, the distinction between morality and ethics is also all but clear. Let us take as an example the translation into different languages as expressed in specialized books: Cicero used “moralis” to translate the Greek “èthikos”. The French “moral” may be translated in German by “ethish” or “moralish”, and in English by “ethical” or “moral”. It seems that from the historical point of view the word “ethics” has been applied to morality considered as well as science or as the way of directing our own behaviour.9 Let us propose some distinctions. On one side, Paul Ricoeur, inspired by Aristotle, defines ethics as “the aim of a good life with and for the other, in just institutions.”10 The major point of view in ethics is that one of living and living together. It is social, collective. It includes the means of solidarity such as culture, habits and customs, i.e. what is contingent and relative.11 On the other side, traditionally, morality (of a person, or an act, or behaviour) or moral is defined as including at least a set of principles of judgment and action which imposes itself 6 7 8 9 10 11 Mark S. Frankel, Professional Codes: Why, How and With What Impact? in: Journal of Business Ethics, Kluwer Academic Publishers, The Netherlands, 8, 1989. Council of Europe, Committee of experts on Ethics of Data Processing, Herbert Maisl, Legal Problems Connected with the Ethics of Data Processing, Study for the Council of Europe, 1979-1982. Criteria and Procedures for Developing Codes of Ethics or of Conduct. To Promote Discussion Inside the IFIP National Societies. On behalf of IFIP-SIG9.2.2: Jacques Berleur, Penny Duquenoy, Jan Holvast, Matt Jones, Kai Kimppa, Richard Sizer, and Diane Whitehouse, Laxenburg, IFIP Press 2004, ISBN 3-90188219-7, available at http://www.info.fundp.ac.be/~jbl/IFIP/cadresIFIP.html André Lalande, Vocabulaire technique et critique de la Philosophie, op. cit., see the words “éthique” and “moral”, pp. 305 and 653. Paul Ricœur, Soi-même comme un autre, Paris, Le Seuil, 1990, p. 202. Paul Beauchamp, Un éclairage biblique sur l’éthique, in ETVDES, Paris, Octobre 1977 (3874), pp. 359369. 2 upon individual conscience founded on the imperatives of ‘the good’. This view of morality may raise difficulties, since it refers to a judgment that is itself founded on the references to an objective knowledge of the moral law as perceived by reason, and to the subjective conscience of the moral norm. In our view, morality is more the domain of the norms, both theoretical and able of being universalized, of the conscience, which assure the integrity of the person. Morality is seen more on the side of the autonomy of the person, rather than in the dimension of solidarity. The reference here is not anymore Aristotle but Immanuel Kant. 12 We may be confused since there are authors who define as ethics what we just defined as morality. So, Deborah Johnson defines ethics as “theories (that) provide general rules or principles to be used in making moral decisions and, unlike our ordinary intuitions, provide a justification for those rules.”13 I found also some other way of expressing the difference between morality and ethics. Morality is a categorical imperative: we shall come back on this term originated from Immanuel Kant. Ethics is an hypothetical imperative, in the sense that action is determined by an hypothesis which leads the behaviour: if you want to achieve that goal, then take that means.14 Let us add finally that there are authors stressing the fact that morality includes the following characteristics: absolute, transcendental, timeless, universal, imperative, expressed in terms if duty; whereas ethics should be characterized as linked to the subject and his/her interiority, respectful for the other, normative but not imperative.15 For the sake of clarity, let us agree on the following orientations: Ethics is more contingent and related to cultures, it has to favour a good life with and for the others, in just institutions; action is specified by an hypothesis; ethics is by essence social and collective, but is not a minimal agreement – it includes the interiority of the subject. Morality is more on the side of principles and norms (both theoretical and ‘universalisable’); the conscience acts by duty; it is more linked to the individual. In the line of the categorical imperative of Immanuel Kant, but not anymore restricted to the individual, Jürgen Habermas has developed a theory of “morality and public spaces”, or an “ethics of discussion” (Ethikdiskurs). He stresses the necessity of creating public spaces, “spaces for discussion”. J. Habermas binds morality and the rights of the human being, morality and the law.16 Here again, we must say that there is a possible conflict of vocabulary: although Habermas is on the Kantian line, he uses the word “Ethikdiskurs”. It may be related to the genius of the language. But we think that is not only that. There are ethical (or moral?) schools and traditions which provide different answers to questions such as: ‘When is an action to be called morally right?’, ‘What is the essence of moral judgments?’, ‘What is the attitude to the freedom of moral decisions? With Deborah 12 13 14 15 16 Ibid. Deborah G. Johnson, Computer Ethics. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, Inc. 11985, 21994, 3 2001. Laurence Bounon, Les rapports entre Ethique, Morale, Déontologie, Droit et Loi, http://perso.wanadoo.fr/usp-lamirandiere/morale_lb.htm Ph. Goujon and B. Hériard Dubreuil, Technology and Ethics, A European Quest for Responsible Engineering, Peeters, Leuven, 2001 Jürgen Habermas, De l’éthique de la discussion, Paris, Cerf, 1992. [Orig.: Erlauterungen zur Diskursethik, Engl. Transl.: Justification and Application: Remarks on Discourse Ethics, Cambridge Mass.: The MIT Press, 1993]. Same author, Morale et Communication, Cerf, Paris, 1986, pp. 86-87. [Engl. Transl.: Moral Consciousness and Communicative Action, Cambridge Mass.: The MIT Press, 1990]. 3 Johnson, but also many other authors, we can distinguish three main trends in the ethical theories. The Figure 1 gives the presentation by Effy Oz.17 Figure 1: Major Ethical Theories Universalism Consequentialism Utilitarianism Relativism Deontologism Non-utilitarianism Kantianism Egoism Consequentialism refers to any type of ethical theories in which right and wrong are based on the consequences of an action. Utilitarianism is one form of consequentialism in which the basic principle is that everyone ought to act in ways that bring about the greatest amount of happiness for the greatest amount of people. Happiness is the ultimate good all creatures are seeking. This theory is strongly based on the English philosophical tradition of Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill: every action must be weighed by the consequences it has. Consequentialism is decision making oriented; utilitarianism is more rule oriented: “Tell the truth”, “Keep your promises”… The weakness of utilitarian theory is that it is ill equipped to deal with issues such as distributive justice; it does not address how benefits and burdens are distributed in a given society. Deontological theories put the emphasis on the character itself, and not on its effects. The right or wrong of an action is the intrinsic character of an action. When the principle of an action can be universalized, the action is good. Therefore, some actions are always good or wrong, no matter what the consequences are. Examples of these principles are: always tell the truth; never kill people whatever the situation may be. At the heart of deontological theories is the idea that individuals are of value and must be treated accordingly. Human beings differ from all other beings in that they have the gift of reason. This theory is strongly based upon the theories of Immanuel Kant, and especially his categorical imperative as expressed in his Grundlegungen zur Metaphysik der Sitten (1785): “I ought never to act except in such a way that I can also will that my maxim should become a universal law18.” Ethical relativism, the third theory or pseudo-theory is more negatively formulated. It denies that there are universal moral norms. Right and wrong are relative, depending on occasions, individuals and one's culture and society. In some societies, polygamy is permissible; in others it is not, and so on. Relativists also point to the fact that moral norms 17 18 Effy Oz, Ethics for the Information Age, Business and Educational Technologies, Wm. C. Brown Publishing, Dubuque, IA, 1994. There are different formulations of that categorical imperative. Immanuel KANT, Groundwork of the Metaphysic of Morals (1785), translated and analysed by H. J. Paton, New York: Harper & Row, 1964, p. 70. 4 change over time so that what is considered wrong at the one time may be considered right at another… When using the terms of ethics and morality, we must be conscious to which school and tradition we are attached. We must also be aware that the last 35 years have also introduced some mistrust if not suspicion in using terms such as morality, denouncing ‘moralism’ and those who give moral lessons and moralize! Ethics has then been preferred, but loosing the normative character of morality. As seen, ethics is social and collective. It has to see with democracy. Some authors do not hesitate to say “Democracy and ethics, in our modernity, merge into one.”19 In that sense, ethics is at risk to be defined by social or parliamentarian majority! Perhaps there is a need to root ethics in morality, making explicit the values we want to promote in ethics. Other clarifications? We are sure that there are other distinctions which are possible, the most important ones could be between professional ethics and deontology, but also considering different qualifications of ethics, such as ethics of responsibility, ethics of discussion, ethics of convictions, business ethics, strategic ethics, descriptive ethics, etc. We don’t think that at this stage it would help us, but we want to mention that reality for further research. The respective roles of ethics, morality, deontology, and the law The traditional mediaeval philosophy mentioned that there are four moral virtues, constituting the field of morality: prudence, justice, temperance and fortitude. The object of the law was justice, and no more. In that sense, what is just is moral, but does not exhaust the domain of morality. On the opposite, we know today’s laws may be, from some point of view, immoral, or at least, amoral. On the other hand, a morality, which would be considered only from the point of view of the individuals, would miss its collective dimension. It would lead, in the long run, to the negation of culture, which is always based on symbols, which represent systems of values. Systems of values are always dependent upon some reachable consensus, or reflect some collective way of life. More fundamentally, there is an intrinsic link between ethics, moral and the law: they aim to define the validity of social practices. The law defines this validity from the point of view of legality, i.e. according to a set of rules which are established along criteria of ‘justiciability’; on the other hand, ethics and moral define this validity from the point of view of its legitimacy, i.e. according to its conformity to extra-legal values or principles which refer to cultural traditions and/or conventions. Many authors consider that the role of professional codes, or today of self-regulation, is mainly to supplement the law, and/or to anticipate it. Herbert Maisl who was leading the group of experts of the Council of Europe stated “the rules of conduct have to reach, beyond the well structured body of computer scientists, the larger circle of computer users. We must shift from a deontology of informaticians to an objective deontology of informatics under the control of the law.20” (We underline) 19 20 J.-Yvon Thériault, Éthique et démocratie chez Habermas, in: Dialogue in Ethics, Centre for Techno-Ethics of Saint Paul University, Ottawa, Canada, vol. 2, 1994, pp. 17-29. Herbert MAISL, Conseil de l'Europe, Protection des données personnelles et déontologie, in: Journal de Réflexion sur l'Informatique, no. 31, Namur (Belgium), Août 1994. 5 We could briefly summarise the different roles of ethics and morality, of the professional codes, and of the law as in Figure 2. Figure 2: Relationships and differences between Ethics, Morality, Codes and Law Subject Object Normativity Enforcement All Convictions Principles Moral Good -> Legitimacy of social practices Quasi-nil No coercion Deontology Codes of ethics/conduct Profession Dignity of profession Behaviour in accordance with the ethical principles Specialized fields Emergence of issues Depending upon the degree of institutionalization From warning to exclusion (depending on the organization of the profession) Law, Conventions, Treaties All Common Good -> Legality of social practices Maximal Sanction Ethics and morality Enforcement “The effectiveness of the different instruments is dependent on an associated power of sanction. Such powers cannot exist in isolation because their ultimate enforcement depends broadly on two organisational attributes - (i) the power of sanction must reside in, and be administered by, a body relevant to a given professional field, such that there is a manifest result applying directly to a given individual and (ii) a third party has to ‘trigger’ the application of the power of sanction by laying a complaint against the individual to whom, in given circumstances, the code applies.”21 This statement does not require many comments. As long as procedures of enforcement, and of complaints are not quite explicit, we are at risk of having instruments, which will remain ineffective! We are convinced that many of the existing codes are unfortunately without defined procedures. The last column of Figure 2 indicates the degree of enforcement of the different kinds of instruments. A last word: we must wonder where the different instruments, codes of deontology, of ethics, of conduct are discussed and received. As stressed when discussing the functions of the codes of deontology, we mentioned that there are functions that define the borders between the profession and the society. In other words there are places for discussion, participation, and reception of the codes. The general public has the right to know which kinds of instruments the professional societies, the firms, the organisations are enacting, and how and with whom they do it. 21 Richard Sizer, Working with Information Systems - the Role of the Professional, in: Jacques Berleur and Chrisanthi Avgerou, Eds., Perspectives and Policies on ICT in Society, Springer Science and Business Media, 2005. 6