Attachment and Social Competence in Adolescence

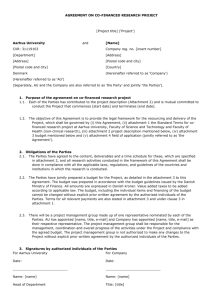

advertisement

Attachment and Adolescent Popularity 1 Attachment, Close Friendship, and Popularity in Adolescence Katherine C. Little Distinguished Majors Thesis University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA April 18, 2003 Advisor: Joseph P. Allen Second Reader: Thomas Oltmanns Running Head: ATTACHMENT AND POPULARITY Attachment and Adolescent Popularity 2 Abstract The goal of this study was to explore how adolescent attachment to parents and adolescent close friendships relate to popularity with peers. A sample of 174 target adolescents were assessed using the Adult Attachment Interview, and peers provided sociometric ratings and measures of companionship about the target adolescents. A secure attachment organization, characterized by consistent discourse about early childhood experiences with parents, was related to higher scores on measures of popularity. Preoccupied attachment, characterized by angry or diffuse discussion of early parent-child experiences, was related to lower peer rankings of popularity. Companionship with a best friend was also positively correlated with popularity, and this effect was separate from the effects of adolescent attachment organization. Results were interpreted as indicating that adolescents’ relationships with parents and close friends, and the correlates of these relationships, both contribute separately to social functioning, specifically popularity with peers. Attachment and Adolescent Popularity 3 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervising professor, Dr. Joseph Allen, for the patience, wisdom, and guidance he expressed as I worked on this project. I am also indebted to Christy McFarland for her help and insight. Martin Ho, Farah Williams, Maryfrances Porter, and the other members of the KLIFF lab were also very helpful and supportive throughout the process of this project. Finally, I would like to extend thanks to my family and friends who have been so encouraging over the course of this year. Attachment and Adolescent Popularity 4 Attachment, Close Friendship, and Popularity in Adolescence An individual’s adolescent years can be among the most turbulent experiences of his or her life. The combination of several factors, including hormonal changes, forming more intimate relationships with peers, dating, and an increase in academic and career pressures are difficult challenges that adolescents face. As teens mature, their tendency is to begin to look more to their peers as sources of support (Steinberg, 2002). However, they appear to learn the patterns of functioning in close relationships from early attachment bonds with parents (Allen & Land, 1999). This study examines how adolescents’ current states of mind with respect to attachment to their parents might influence later relationships with peers. Attachment: From Infancy to Adolescence A person’s first and most basic relationship is the attachment bond. This is a unique bond that is formed in infancy between a child and at least one specific caregiver, almost always a parent. Once an attachment relationship is formed, the infant desires to maintain contact with the attachment figure and displays affective distress when that person is unavailable (Cassidy, 1999). The attachment relationship with the parental attachment figure allows the child to explore and learn about the physical world, but when the world becomes too stressful, the infant seeks comfort from the parent as a safe haven. In this way, the parent acts as a “secure base” from which the infant can safely explore (Weinfield, Sroufe, Egeland, & Carlson, 1999; Ainsworth, 1991). Based on experiences in this relationship, the infant begins to develop an internal working model of himself, and this model is a representation of how accepted or unaccepted a child feels in the eyes of his attachment figures (Meins, 1997; Bowlby, 1973). This Attachment and Adolescent Popularity 5 model, known as an internal working model, helps the child to formulate strategies for getting his needs met by the parents. The child will use this model until it is no longer useful in the relationship, at which point the child will alter the model to fit the new circumstances. One popular procedure for examining this attachment relationship, between a child under two years of age and a specific caregiver, is the Strange Situation (see Ainsworth & Wittig (1969) for thorough coverage of this procedure). Although some research has found no positive correlation between infant attachment and later attachment (Lewis, Feiring, & Rosenthal, 2000; Weinfield, Sroufe, & Egeland, 2000), other research has found that internal working models and attachment security tend to be at least somewhat stable over time (Waters, Weinfield, & Hamilton, 2000; Hamilton, 2000; Waters, Merrick, Treboux, Crowell, & Albersheim, 2000), Thus, an infant’s early experiences with parents may have an impact on his relationships for the rest of his life. Unlike childhood, where exploration tends to be limited to the physical world, exploration in adolescence is about exploring new emotional terrain, often in the form of relationships with peers and romantic partners (Allen & Land, 1999). Thus, the nature of the attachment relationship of an adolescent with his parents evolves into a strategy for managing intense affect (Allen & Land, 1999; Kobak & Sceery, 1988), and it is hypothesized that organization of the attachment relationship in adolescence is less about interactions in the parentchild relationship, and more about how the teenager conceptualizes this relationship (Allen & Land). The Adult Attachment Interview (AAI) was developed by George, Kaplan, & Main (1985) to assess adults’ representations of their relationships with their parents, and also to validate whether parents’ representations of relationships correspond to their infants’ attachment organizations. Unlike the Strange Situation (see Ainsworth, 1969), the AAI does not measure a person’s attachment organization with respect to a particular figure. Instead, the AAI measures Attachment and Adolescent Popularity 6 an adolescent’s general state of mind with respect to attachment. A growing body of evidence supports the validity of the AAI as a measure of attachment in adulthood and adolescence (Kobak & Sceery, 1998; Main, Kaplan, & Cassidy, 1985). The coding system for the AAI uses four categories of attachment organization: secure/autonomous, dismissing, preoccupied, and unresolved. Securely attached adolescents are able to produce a coherent narrative of their own childhood and their parents’ behaviors toward them, even if the experience was not positive (Kobak & Sceery). Adolescents coded as dismissing with respect to attachment, give responses that tend to be contradictory or characterized by an inability to remember details from childhood. Adolescents classified as preoccupied with attachment give responses that are angry, rambling, and sometimes internally conflicting. The unresolved category of attachment is reserved for teens caught up in the feelings of loss of a parent (Meins, 1997). Attachment and Peer Relationships The adolescent’s attachment organization is expected to influence peer relationships in several ways. Generalizing from research using late childhood samples, attachment organization may impact the teen’s social expectations about whether and how well his or her needs will be met in intimate relationships, the teen’s feelings of self-worth or self-efficacy for whether he or she feels worthy of having her needs met, whether he or she can have an influence on how others interpret those needs, and how well the teen can reciprocate liking in relationships (Elicker, Englund, & Sroufe, 1992). However, these constructs have not been thoroughly examined in adolescent samples. In addition, some developmental tools that are likely to be learned from the parent-child attachment relationship may transfer to peer relationships, tools such as affect regulation, empathy, reciprocity, conflict resolution skills, self-esteem, and interpersonal Attachment and Adolescent Popularity 7 understanding (Elicker, et al., 1992). It is important to note that the attachment relationship does not transfer from the parent to the teen’s peers; attachment relationships are, by definition, specific to a certain person and are persistent throughout the life course (Ainsworth, 1989; Cassidy, 1999). One other point to note is that the focus of the current study is the adolescent’s state of mind with respect to attachment, not any individual attachment relationship. Thus, teens suffering from acute stress or threatening circumstances may discuss the problem with an intimate close friend, but will usually turn to a parental attachment figure for deep comforting and support. Popularity vs. Friendship When discussing adolescent peer relationships, it is important to make a distinction between popularity and friendship: close, intimate friendships reflect a bond between two individuals who reciprocally like one another, whereas popularity refers to how the teen functions in a peer group (Bukowski et al., 1996). Another way of conceptualizing the differences between friendship and popularity is in terms of individual qualities that make the experiences of both meaningful. Close friendships often evolve to meet specific needs, and can be evaluated by both parties. Involvement in the peer group rewards for leadership and assertiveness, gives a sense of a larger community, and is typically evaluated unilaterally, or, in other words, most individuals do not have a say in how popular they are (Bukowski et al.). Popularity is frequently measured with a sociometric nomination procedure, of which there are many varieties. In sociometric measurement, participants nominate peers as either liked or disliked (some researchers prefer to use positive nominations only). These ratings can be limited, for example, children may be asked to nominate only their 5 best- and least-liked Attachment and Adolescent Popularity 8 peers; or ratings can be unlimited, for example, a question that asks participants to rate all peers in their class that they like and all peers that they dislike. Throughout the literature, two main types of analysis have emerged. First is the single-dimensional system, which measures sociometric status by the number of positive and/or negative nominations a child receives (Coie & Dodge, 1988; Newcomb, Bukowski, & Pattee, 1993). In this system, the number of positive nominations is communicated as social acceptance, and the number of negative nominations is known as rejection (Coie, Dodge, & Coppotelli, 1982). This method has been criticized for the possibility that strictly positive or negative nomination is not sufficiently sensitive to detect relationships between popularity and other variables (Jarvinen & Nichols, 1996). The other method is a two-dimensional system, which includes measures of acceptance and rejection, but also uses different combinations of these scores to include more types of peers; specifically, controverciality or social impact, which is defined as relative notice by peers, and is the sum of acceptance and rejection scores; and neglect, which is the relative invisibility to peers, and occurs when children do not score significantly highly on acceptance or rejection (Coie & Dodge, 1988; Newcomb, et al., 1993) . One special type of nomination procedure is the roster-and-ratings scale procedure, which asks participants to rate all peers within a certain classroom or throughout the entire grade level on a Likert scale from least to most preferred. Some researchers strongly advocate the use of a roster-and-ratings scale to measure sociometric status among children, because it gives information about exactly how much each participant likes every other peer (Parker & Asher, 1993). However, this method is impractical for measuring sociometric status among large samples of adolescents, who may be in schools that are so large that they are unfamiliar with many of their peers or for whom filling out sociometric nominations for hundreds of peers would Attachment and Adolescent Popularity 9 be unnecessarily taxing. Based on the variability of sociometric procedures in the literature, it can be confusing and difficult to compare research studies that use sociometric measurement. However, it should be clear that some measures are more appropriate for certain samples than others. Measurements of friendship are comparatively less messy. Determining the existence of a close reciprocal friendship is often as simple as having a child or adolescent rank his or her top three “best” friends, and compare those to the rankings made by the three friends (Bukowski, et al., 1996). The quality of a reciprocal friendship is useful because it is related both to attachment and popularity. The constructs measured by typical surveys of friendship quality: emotional support, trust, companionship, self-disclosure, and sensitivity to the needs and desires of others, are naturally relevant to popularity (Parker & Asher, 1993). This study focuses on companionship in particular. Companionship in childhood or adolescent relationships is defined as the extent to which friends seek each other out to spend fun time together, both in and out of school. As adolescents begin to seek out peers over parents as a source of social interaction and enjoyment, they spend increasing amounts of time with a best friend or a group of close friends (Steinberg, 2002). In fact, Steinberg notes that over 50 percent of an adolescent’s day is spent with peers (including time at school), whereas only 15 percent is spent with parents and other adults. Spending time with friends is obviously related to popularity, in fact, it is crucial to the formation of a group’s opinion of an individual. The relationship between attachment and companionship is not as clear, and in fact, there is very little research that has either studied or found any significant relationship between the two (Lieberman, Doyle, and Markiewicz, 1999). Attachment and Adolescent Popularity 10 Why study popularity? The effects of popularity can be dramatic on a teen, a peer group, and teens’ families. To some teens and their parents, popularity can seem like a four-letter word, and to others, like a shining tiara. Research suggests it can be both: the pressure to be popular with peers can have positive and negative consequences. In early adolescence, the pressure to be viewed favorably by peers may encourage young adolescents to pay more attention to personal hygiene and appearance (Steinberg, 2002). On the flip side, concerns about popularity are also related to body satisfaction and eating disorders (Lieberman, Gauvin, Bukowski, & White, 2001). Teens in search of positive regard by their friends may experiment outside of their comfort zones, for example, by trying a new sport, club, or class; but on the other hand, popularity is correlated with teen experimentation with smoking (Alexander, Piazza, Mekos, & Valente, 2001). An adolescent’s sociometric rating in the peer group has general behavioral correlates, as well. Popularity is correlated with higher sociability, higher cognitive abilities, lower levels of aggression, lower levels of withdrawal, the ability to be assertive when necessary, and good facilitation of the goals of peers (Coie & Dodge, 1988; Newcomb, et al., 1993). Popularity clearly has many important correlates and implications for adolescent development and functioning. Research on the Relationship Between Attachment and Popularity The link between adolescent attachment to parents and peer relationships is complex. Studies of the relationship between childhood attachment and social competence help trace a progression of early peer and parent relationships and link them with relationships in Attachment and Adolescent Popularity 11 adolescence. Popularity measures in childhood are appropriate ways to measures social competence and social acceptance because the social network throughout most of childhood tends to be a large peer group, with a few close friends. This is especially true for young boys, who tend to travel in “packs,” while girls tend to pick a few close friends with whom they spend time (Denham, et al., 2001). Overall, secure children seem to be better adjusted to the intellectual, social, emotional, and behavioral demands of an early school environment than insecure children, who tend to be more rejected and less well-liked by peers (Cohn, 1990; Granot & Mayseless, 2001). More specific to insecure attachment, avoidant and disorganized attachment patterns in children are linked to higher levels of peer rejection, whereas ambivalent children tended to score in the average range on measures of peer rejection, but perceived this rejection rate to be much higher than that reported by their peers (Granot & Mayseless, 2001). There are also gender differences in the relationship between attachment security and peer relations in childhood; secure boys may be found more often in positive, socially competent playgroups; while secure girls apparently are more likely to be found in negative, less socially competent playgroups (Denham, et al., 2001). Lefreniere and Sroufe (1985) found resistantly attached girls to be robustly passive, withdrawn, submissive, and neglected around peers. In another study, insecure boys were rated as less socially competent than insecure girls (Cohn, 1990). Granot and Mayseless (2001) found that boys were significantly more often avoidant or disorganized, and that girls were more often secure; however, this is an Israeli sample and may be difficult to generalize to more Western populations. Unfortunately for the current study, the above research was conducted exclusively on childhood and preschool samples. Some research on social functioning in adolescence is consistent with the findings of childhood studies, however there are comparatively fewer studies of the relationship between Attachment and Adolescent Popularity 12 adolescent attachment and social competence or popularity with peers. In a study of first-year college students, Kobak and Sceery (1988) found a significant contrast between securely attached participants and those classified as preoccupied across self-report measures of perceived social competence. Using self-report only measures of social functioning could be problematic, because the way an adolescent functions in a peer group may be perceived differently by that adolescent and members of the peer group (Belsky & Cassidy, 1995; Bukowski et al., 1996). In a more recent study, Allen, Moore, Kuperminc, & Bell (1998) found a robust positive relationship between secure attachment (AAI) and social acceptance, as reported on a target adolescent by two different peers. This significant relationship remained even after controlling for age, gender, income, minority status, and parents’ marital status. There was also a trend toward a negative relationship between preoccupied attachment and social acceptance. Allen, et al. (1998) also found that a secure attachment relationship appeared to predict social acceptance. More broadly, Allen et al. suggest that the capacity of a securely attached adolescent to process attachment-related emotions and memories coherently is linked to multiple aspects of psychosocial functioning in adolescence. Therefore, there is some evidence to suggest that the attachment relationship may indeed serve as an internal working model for numerous types of social interactions throughout childhood and adolescence. Despite these findings, Lieberman, Doyle, and Markiewicz (1999) did not find a significant relationship between attachment and social acceptance in a Canadian sample of older children and early adolescents. The participants’ attachment security was measured by the Kerns Security Scale (KSS; Kerns, Klepac, & Cole (1996)), and the adolescents also each completed a measure of friendship quality about a reciprocal best friend and a measure of sociometric status. Lieberman, et al. (1999) found attachment security to be significantly correlated with friendship Attachment and Adolescent Popularity 13 quality, in that adolescents that viewed their parents as more available and reliable in times of stress also reported more positive qualities and less conflict in their close friendships. Interestingly, neither companionship nor popularity with peers was significantly related to attachment security. Lieberman, et al. reason that this lack of findings is because attachment as an organizational construct is more appropriate to compare to other intimate relationship constructs, and that popularity does not fit into this theoretical model. Another possible reason for these findings is that the KSS, unlike the AAI, is a self-report questionnaire that explicitly asks children to rate how available, reliable, and communicative they think their parents are. The AAI, in contrast, is a measure of the underlying structure of the attachment system that tries to explore peoples’ implicit feelings and thoughts about their relationship with their parents. The KSS is also specific to individual parental attachment relationships, thus it wouldn’t make sense for the measure to predict non-close relationship characteristics. Moreover, the AAI might give a more global impression of the internal working model, as compared to the KSS, and this may be more generalizable to non-intimate relationship contexts. Despite measurement differences, Lieberman, et al.’s study design suggests the need to examine the different roles that attachment and peer relationships play in broader social functioning. This study examines how two different constructs, attachment to parents and companionship with a close friend, relate to one aspect of adolescent social functioning: popularity. Hypotheses of the current study Based upon the theory and literature in the field of attachment and social relationships, three relationships between attachment security and social acceptance are proposed. First, a secure attachment will be predictive of greater popularity. Second, preoccupied attachment will Attachment and Adolescent Popularity 14 be predictive of lesser popularity. Third, the quality of companionship with a close friend will predict popularity separately from and in addition to attachment organization. In other words, we are considering an adolescent’s relationship with his or her peers separately from his or her relationship with a best friend, in order to see how each might add to our understanding of teenage popularity. Attachment and Adolescent Popularity 15 Method Participants Participants in this study are drawn from a larger longitudinal study of adolescent development and peer and parent relationships. Data collection for the current study took place in the second year of the ongoing study. In the second wave of the study, participants were 174 seventh, eighth, and ninth grade students. There were 82 males and 92 females who agreed to participate (age: M = 14.26, SD = .78). The sample was diverse racially/ethnically (61% European American and 39% African American, other minority group, or mixed), as well as with respect to socioeconomic status, with a median family income of $50,000. At each wave, adolescents nominated a single closest friend to be included in the study, as well as two other peers who were ranked by the target adolescents as their fourth closest and eighth closest friends. Close friends reported that they had known the target adolescents for a mean of 4.46 years (SD = 0.75) at the second wave. Procedure Adolescents were recruited prior to Wave 1 from the seventh and eighth grades at a public middle school in a part urban, part suburban area in the Southeastern United States. Mailings were sent to the parents of all students at the school, and were followed by contact efforts at school lunches. Adolescents who expressed interest in the study were contacted by telephone, and of those eligible, 63% agreed to participate as either a target participant or as a peer providing information about the target adolescent. All participants provided informed assent before each interview session, and parents provided active, informed consent. Interviews took place in private offices within a university academic building. Attachment and Adolescent Popularity 16 During the first year of the study, the target adolescents’ parents reported on total annual household income. At the second wave/year of data collection, spaced approximately one year apart from the first wave, adolescents completed two visits: first alone and then again with their previously named close peer. At the first visit, target adolescents listed their twelve closest friends and ranked them from closest to least close. The peer identified as number one was contacted by phone as the “close peer” to complete measures in a joint visit with the target teen at visit two. The two peers identified as the target adolescent’s fourth- and eighth-closest friends were also contacted to come in separately and fill out measures about their own behavior and their relationship with the target adolescent. Parents, target adolescents, and peers were all paid for their participation. Transportation and childcare were provided, if necessary. Measures Attachment: The Adult Attachment Interview (AAI) and Q-set. (George, Kaplan, & Main, 1995; Kobak, Cole, Ferenz-Gillies, Fleming, & Gamble, 1993). Adolescents were administered the Adolescent Attachment Interview, a form of the Adult Attachment Interview modified for use with adolescents (Ward & Carlson, 1995). The AAI is a semi-structured interview that asks adolescents about childhood experiences, using both semantic and episodic memories. Adolescents are asked to describe their childhood relationship with their parents in the form of five adjectives (semantic memories). They are then probed to provide a specific example or memory of their parents that exemplifies each adjective (episodic memories). The individual’s responses are audio taped, transcribed, and then coded based upon overall coherence and the ability of the interviewee to integrate semantic and episodic memories. The entire interview lasts about 1 hour. Attachment and Adolescent Popularity 17 The AAI Q-set (Kobak, et al., 1993). Adolescents’ attachment status was determined by Q-sort coding the AAI (George, Kaplan & Main, 1985; Kobak et al., 1993). Interviews were classified for overall states of mind with respect to attachment. This study focused on two types of attachment organization, secure and preoccupied. Secure attachment is characterized by consistent discourse about early childhood experiences with parents, whereas preoccupied attachment is characterized by angry or diffuse discussion of early parent-child experiences (Ainsworth, 1989; Ainsworth & Bowlby, 1991; Allen & Land, 1999). Spearman-Brown splithalf reliability for secure attachment was .83 and of preoccupied attachment was .80. Companionship. The Friendship Quality Questionnaire (Parker & Asher, 1993) was designed to assess adolescents’ conceptualization of the quality of their relationships with their closest friend. The companionship and recreation subscale was used to measure the extent to which friends spend enjoyable time with one another (Parker & Asher). The target adolescent and their nominated close friend each completed the FQQ about one another. The construct measured by the companionship and recreation subscale will hereafter simply be referred to as companionship. Popularity. Adolescent popularity was measured by a sociometric nominating procedure that was completed by the target adolescents, their closest peer, and the fourth- and eighthclosest friends. Because the sample was contained in one school, it was possible for target adolescents, close peers, and other peers to be nominated multiple times to fill out questionnaires. If an adolescent filled out questionnaires about more than one peer over the course of a particular wave, he or she only completed the sociometrics procedure once. Adolescents were asked to provide positive nominations: “the ten students in your grade that you would most like to spend time with on a Saturday night,” and these nominations were explicitly Attachment and Adolescent Popularity 18 limited to within-grade peers. If an adolescent had fewer than ten peers to nominate, they were gently instructed by the interviewer to nominate as many as possible. Nominations were standardized according to the procedures set forth by Coie and Dodge (1983, 1988). Negative nominations were also collected, but were not analyzed for the purpose of this study. Results Preliminary Analyses Sample Means. Means and standard deviations of attachment, popularity, and companionship are presented in Table 1. Mean attachment scores are similar to those of a sample of adolescents with academic risk factors (Allen et al., 1998), and to a normative sample of adolescents (Kobak et al., 1993). Table 1 Means and Standard Deviations of Attachment, Social Acceptance, Companionship, and Demographic Variables Variables M SD Adolescent Attachment Security (I) .28 .42 Adolescent Attachment Preoccupation (I) -.02 .23 Adolescent Attachment Dismissing (I) .03 .42 Popularity/Social Acceptance (Combined score from A, CP, .92 1.23 OF) Companionship (A) 20.09 4.18 Companionship (CP) 19.51 4.41 Note: I – Coded from Interviews; A – Adolescent Reported; CP – Close Peer Reported; OF – Other Friend Reported Intercorrelations of Attachment Measures. Preliminary correlations were run among attachment scales to test for significant relationships within the measure (Table 2). A strong Attachment and Adolescent Popularity 19 negative correlation between secure and dismissing attachment was found (r = -.93, p < .001). Therefore, for the remainder of the analyses, only secure and preoccupied attachment scales were used, in order to avoid the redundancy implied by including the dismissing scale. Table 2 Univariate Correlations of Attachment Variables Adolescent Preoccupied Attachment -.54*** Adolescent Secure Attachment Adolescent Preoccupied Attachment Note: *** p < .001. ** p < .01. * p < .05. + p < .10. N = 144 Adolescent Dismissing Attachment -.93*** .46*** Demographic Variables. Preliminary correlations of attachment, popularity, and companionship with demographic variables tested for significant relationships therein. As seen in Table 3, significant correlations were obtained between family income and attachment scales (r = .33, p < .001 secure; r = -.36, p < .001 preoccupied), and income and popularity (r = .34, p < .001). Participant gender was also correlated with preoccupied attachment (r = .23, p < .01). Table 3 Univariate Correlations of Demographic Variables with Attachment, Popularity, and Companionship Variables Adolescent Secure Attachment Adolescent Preoccupied Attachment Companionship (Adolescent Reported) Companionship (Close Peer Reported) Popularity Gender Note: *** p <.001. ** p < .01. * p < . 05. N = 129 Gender .08 .23** .08 .03 -.02 Income .33*** -.36*** .04 .02 .34*** -.13 Attachment and Adolescent Popularity 20 Primary Analyses Correlations among measures of attachment, popularity, and companionship were run with income and gender partialed out. The results of these partial correlations are presented in Table 4. Table 4 Partial Correlations Among Attachment and Friendship Measures (Partialing out Gender and Income) 1 1. Adolescent Secure Attachment 2. Adolescent Preoccupied Attachment 2 -.55*** 3 4 5 .30*** .14 .14 -.20* -.07 -.09 3. Popularity .28** 4. Companionship (Self Report) .24** .64*** 5. Companionship (Close Peer Report) Note: *** p <.001. ** p < .01. * p < . 05. N = 129 After determining several significant correlations, hierarchical regression analyses were used to further examine the relationship between attachment, companionship, and popularity. In step one, adolescent gender and family income were entered as demographic variables. In each regression step two consisted of attachment organization, with analyses run separately for secure and preoccupied attachment. In step three the close friend’s report of companionship in the dyad was entered, followed by the target adolescent’s self report of companionship. Secure Attachment. Secure attachment was moderately positively correlated with popularity (r = .30, p < .001), even after partialing out income and gender (see Table 4). Attachment and Adolescent Popularity 21 However, we found no significant relationship between attachment and either close peer or selfreports of companionship. In a regression analysis, (Table 5), secure attachment added to 9 percent of the variance in popularity, over and above demographic variables (entry = .30, F = 12.62, p < .001). Table 5 Predicting Adolescent Social Acceptance from Secure Attachment and Companionship (Controlling for Demographic Factors – Gender and Income) Variables Step I. Gender Family Income (Age 13) Statistics for step I Adolescent Popularity (entry) (final) -.03 -.04 .34*** .24** Step II. Secure Attachment Step III. Companionship (Peer Report) Companionship (Self Report) Statistics for step III .30*** .27** .19* .07 .18+ .18+ R2 Total R2 .11*** .11*** .09*** .20*** .05*** .25*** Note: *** p <.001. ** p < .01. * p < . 05. + p < .10. Model N = 128 Preoccupied Attachment. As noted in Table 6, preoccupied attachment was negatively correlated with popularity (r = -.20, p < .05). Preoccupation, like security, had no significant correlation with either report of companionship. In regression analysis, preoccupied attachment added 4 percent over and above the variance in popularity explained by demographic factors (entry = -.20, F = 4.97, p < .05). Attachment and Adolescent Popularity 22 Table 6 Predicting Adolescent Social Acceptance from Preoccupied Attachment (Controlling for Demographic Factors – Gender and Income) Variables Step I. Gender Family Income (Age 13) Statistics for step I Step II. Preoccupied Attachment Step III. Companionship (Peer Report) Companionship (Self Report) Statistics for step III Adolescent Popularity/Social Preference/Acceptance (entry) (final) R2 -.03 .04 .34*** .27** -.20* -.17+ .21* .09 .19+ .19+ Total R2 .11*** .11*** .04*** .15*** .06*** .21*** Note: *** p <.001. ** p < .01. * p < . 05. + p < .10. Model N = 128 Companionship. Both the close peer’s report and the target adolescents’ report of companionship were included in the regression analyses. By doing this, we hoped to provide multiple accounts and an accurate representation of the quality of companionship in the relationship, while attempting to minimize the problems associated with relying on exclusively self-report data. Due to a strong (yet far from perfect) positive correlation between the two reporters (r = .64, p < .001), we believe that combining the two reports into a single step in the regression analyses provided the best overall model for assessing the impact of companionship on popularity. In regression analyses, peer report and adolescent self report of companionship were added (in that order) in step three of the model. In the secure attachment model, the combined addition of companionship scores explained 5 percent of the variance in popularity Attachment and Adolescent Popularity 23 over and above secure attachment organization and demographic variables (see Table 5 for beta weights). In the preoccupied attachment model, combined scores of companionship explained an additional 6 percent of the variance in popularity over and above preoccupied attachment and demographic variables (see Table 6 for beta weights). Final beta weights were included in Tables 5 and 6 in order to express the changes in beta weight that took place throughout the regression analyses. Specifically, when peer and selfreports of companionship were added to the model, the preoccupied attachment beta weight became a nonsignificant finding (see Table 6). Another surprising finding was the effective annihilation of the significance of the beta weight of the close peer’s report of companionship by the target adolescent’s self-report companionship score. Although each report contributed separately and significantly to the increase in explained variance in popularity, the target adolescent’s own perception appears to be a stronger predictor of this increase than the close friend’s. Interestingly, despite previous findings in childhood samples where gender was strongly linked to differences in attachment and social acceptance (Denham, et al., 2001; Granot & Mayseless, 2001), gender did not account for any significant percentage of the variance in popularity for either the secure or preoccupied models. Discussion The hypotheses this study examines appear to have general support from the analyses presented. Secure attachment was robustly positively correlated with popularity, even when taking gender and family income into account. Secure attachment organization also explained a significant amount of the variability in popularity, over and above that explained by demographic variables. Therefore, there is evidence to suggest that a secure attachment relationship does Attachment and Adolescent Popularity 24 contribute to an adolescent’s popularity within the peer group. This is consistent with previous research on attachment and social functioning, and may imply that, because of early parent-child interactions and subsequent states of mind regarding attachment, secure adolescents have developed relationship skills better suited to positive social interactions. In other words, securely attached adolescents may be better equipped to learn the art of graceful social exchange. The second hypothesis, that adolescents who are preoccupied with attachment tend to be less popular with peers, is also supported by this study’s findings. Adolescents with preoccupied attachment strategies were less likely to be popular with their peers, and this result was found over and above the relationship of gender and income with popularity. Previous research has found that preoccupied children are not only less popular with their peers, they are also explicitly rejected by peers (Granot & Mayseless, 2001). More importantly in terms of attachment organization, preoccupied children expect even higher levels of rejection than they actually receive. Therefore, preoccupied adolescents, whose normal developmental progression (like most adolescents) is to seek more autonomy from parents and more interactions with peers, may be caught up in worries over acceptance by parents, and to this is added the additional stress of the struggle for acceptance by peers. These teens may spend so much effort racing around, mentally evaluating relationships, that they do not allow themselves a chance to “breathe.” It is no wonder that these teens, who have the potential to be constantly stressed about relationships, are less popular with their peers. The third hypothesis, that companionship is related to popularity separately and additively to attachment organization, is also supported. Higher quality of companionship (for both peer and target adolescent reports) was found to be associated with adolescent popularity with peers, and the combined companionship scores also explained a small percentage of the Attachment and Adolescent Popularity 25 variance in popularity in addition that explained by both secure and preoccupied attachment. This speaks to Lieberman et al.’s (1999) assertion that attachment ought only be related to other intimate relationship constructs. Based upon the results of this study, an alternative to this conclusion is that both an adolescent’s state of mind with respect to attachment and the quality of companionship with close friends can influence popularity in separate ways. This hypothesis is made stronger by the finding that neither secure nor preoccupied attachment was correlated with reports of companionship, so we may speculate that these two constructs are influencing popularity in meaningfully different ways. Potential reasons for this finding are discussed below. In the preoccupied model, beta weights of preoccupation declined from a significant finding at entry into the model to nonsignificant finding after companionship was entered. What we propose this means is that, for preoccupied adolescents, having a close friend with whom they spend a great deal of time may serve several purposes. First, spending time with one close friend might be a distracting factor; thus helping prevent a preoccupied adolescent from being alone and worried about what his friends, parents, and other peers think about him. Second, simply having a close friend who is potentially understanding might provide a preoccupied teen with a safe “breathing space” from which to more calmly evaluate relationships. Third, having a close friend with whom one spends a large portion of time may provide more opportunities for comfortable interactions with additional peers. We should note that time spent with a close friend is not necessarily quality time, and that future research should assess preoccupied teens’ interactions with their close friends. Knowing the close friend’s attachment status would also be useful, for example, in order to explore whether preoccupied teens who have secure close friends are more popular and/or socially Attachment and Adolescent Popularity 26 accepted than preoccupied teens with insecurely attached close friends. Future research could also examine additional specific aspects of social functioning that may be related to both attachment organization and adolescent popularity. Constructs such as affect regulation, self esteem, and conflict resolution skills may serve to better explain how attachment and companionship jointly and separately contribute to popularity. Some limitations of this study are tied into the measurement of sociometric status. Because the sample of sociometrics reporters was not randomly selected, it may not be representative of the entire school’s popularity structure. Additionally, because it was particularly difficult to contact adolescents’ peers of the lowest income brackets, results may be biased to a sample of higher socioeconomic status. Limitations tied to attachment measurement include the use of the Q-sort procedure, which does not allow for the identification of the insecure/unresolved category of attachment organization. This is not highly problematic or invalidating to the results of this study, but including this category in future research could help to provide a more detailed examination of attachment states of mind and their relationship to various aspects of adolescent social functioning. In conclusion, the researchers of the current study set out in an attempt to better understand how adolescents function socially, in the context of both parental and peer relationships. There is no suggestion that certain attachment states of mind or qualities of companionship cause an adolescent to be more or less popular. Popularity may be influencing the quality of an adolescent’s companionship with a close friend in ways we have not explored, and it is possible, though theoretically unlikely, that popularity may have some effect on an adolescent’s state of mind with respect to attachment. The findings of this study are relatively Attachment and Adolescent Popularity 27 simple; however, they are exciting in the sense that future researchers can use them as steppingstones to more in-depth and applied studies of adolescent development. Attachment and Adolescent Popularity 28 References Ainsworth, M. D. S. (1989). Attachments beyond infancy. American Psychologist, 44(4), 709716. Ainsworth, M. D. & Bowlby, J. (1991). An ethological approach to personality development. American Psychologist, 46(4), 333-341. Ainsworth, M. D. & Wittig, B. A. (1969). Attachment and exploratory behavior of one year olds in a strange situation. In B. M. Foss (Ed.), Determinants of Infant Behaviour, 4. London: Methuen; New York: Barnes and Noble. Allen, J. P & Land, D. (1999). Attachment in adolescence. In J. Cassidy & P. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of Attachment: Theory, Research, and Clinical Applications (pp. 319-335). New York, NY: The Guilford Press. Allen, J. P., Moore, C., Kuperminc, G., & Bell, K. (1998). Attachment and adolescent psychosocial functioning. Child Development, 69(5), 1406-1419. Alexander, C., Piazza, M., Mekos, D., & Valente, T. (2001). Peers, schools, and adolescent cigarette smoking. Journal of Adolescent Health, 29, 22-30. Bukowski, W. M., Pizzamiglio, M. T., Newcomb, A. F., & Hoza, B. (1996). Popularity as an affordance for friendship: The link between group and dyadic experience. Social Development, 5(2), 190-202. Bowlby, J. (1973). Attachment and Loss: Vol. 2 – Separation. London: Hogarth Press. Cassidy, J. (1999). The nature of the child’s ties. In J. Cassidy & P. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of Attachment: Theory, Research, and Clinical Applications (pp. 3-20). New York, NY: The Guilford Press. Attachment and Adolescent Popularity 29 Cohn, D. A. (1990) Child-mother attachment of six-year-olds and social competence at school. Child Development, 61(1), 152-162. Coie, J. D., & Dodge, K. A. (1983). Continuities and changes in children’s social status: A fiveyear longitudinal study. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 29, 261-281. Coie, J. D., & Dodge, K. A. (1988). Multiple sources of data on social behavior and social status in school: A cross-age comparison. Child Development, 59, 815-829. Coie, J. D., Dodge, K. A., & Coppotelli, H. (1982). Dimensions and types of social status: A cross-age perspective. Developmental Psychology, 18, 557-571. Denham, S., Mason, T., Caverly, S., Schmidt, M., Hackney, R., Caswell, C., & DeMulder, E. (2001). Preschoolers at play: Co-socializers of emotional and social competence. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 25(4), 290-301. Elicker, J., Englund, M., & Sroufe, L. A. (1992). Predicting peer competence and peer relationships in childhood from early parent-child relationships. In R. D. Parke & G. W. Ladd (Eds.), Family-Peer Relationships: Modes of Linkage (pp. 77-106). New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. George, C., Kaplan, N., & Main, M. (1985). The Attachment Interview for Adults. Unpublished manuscript, University of California, Berkeley. Granot, D. & Mayseless, O. (2001). Attachment security and adjustment to school in middle childhood. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 25(6), 530-541. Hamilton, (2000) Jarvinen, D. W., & Nichols, J. G. (1996). Adolescents’ social goals, beliefs about the causes of social success, and satisfaction in peer relations. Developmental Psychology, 32(3), 435 441. Attachment and Adolescent Popularity 30 Kerns, K. A., Klepac, L., & Cole, A. K. (1996). Peer relationships and preadolescents’ perceptions of security in the mother-child relationship. Developmental Psychology, 32, 457-466. Kobak, R. R., Cole, H. E., Ferenz-Gillies, R., Fleming, W., Gamble, W. (1993). Attachment and emotion regulation during mother-teen problem solving: a control theory analysis. Child Development, 64(1), 231-245. Kobak, R. R. & Sceery, A. (1988). Attachment in late adolescence: Working models, affect regulation, and representations of self and others. Child Development, 59, 135-146. Lefreniere, P. J., & Sroufe, L. A. (1985). Profiles of peer competence in preschool: Interrelations between measures, influence of social ecology, and relation to attachment history. Developmental Psychology, 21(1), 56-69. Lewis, M., Fiering, C., & Rosenthal S., (2000). Attachment over time. Child Development, 71(3), 707-720. Lieberman, M., Doyle, A., Markiewicz, D. (1999). Developmental patterns in security of attachment to mother and father in late childhood and early adolescence: Associations with peer relations. Child Development, 70(1), 203-213. Lieberman, M., Gauvin, L., Bukowski, W. M., & White, D. R. (2001). Interpersonal influence and disordered eating behaviors in adolescent girls: The role of peer modeling, social reinforcement, and body-related teasing. Eating Behaviors, 2(3), 215-236. Main, M., Kaplan, N., & Cassidy, J. (1985). Security in infancy, childhood, and adulthood: A move to the level of representation. In I. Bretherton & E. Waters (Eds.), Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 50 (Serial No. 209, pp. 66-104). Attachment and Adolescent Popularity 31 Meins, E. (1997). Security of Attachment and the Social Development of Cognition. Staffordshire, UK: Psychology Press. Newcomb, A. F., Bukowski, W. M., & Pattee, L. (1993). Children’s peer relations: A meta analytic review of popular, rejected, neglected, controversial, and average sociometric status. Psychological Bulletin, 113(1), 99-128. Parker, J. G. & Asher, S. R. (1993). Friendship and friendship quality in middle childhood: Links with peer group acceptance and feelings of loneliness and social dissatisfaction. Developmental Psychology, 29(4), 611-621. Steinberg, L. (2002). Adolescence. Boston: McGraw Hill. Ward, M. J. & Carlson, E. A. (1995). Associations among adult attachment representations, maternal sensitivity, and infant-mother attachment in a sample of adolescent mothers. Child Development, 66, 69-79. Waters, E., Merrick, S., Treboux, D., Crowell, J., & Albersheim, L. (2000). Attachment security in infancy and early adulthood: A twenty-year longitudinal study. Child Development 71(3), 684-689. Waters, E., Weinfield, N., & Hamilton, C. E. (2000). The stability of attachment security from infancy to adolescence and early adulthood: General discussion. Child Development, 71(3), 703-706. Weinfield, N., Sroufe, L. A., Egeland, B., & Carlson, E.A. (1999). Attachment from infancy to early adulthood in a high-risk sample: Continuity, discontinuity, and their correlates. Child Development, 71(3), 695-702. Attachment and Adolescent Popularity 32 Weinfield, N., Sroufe, L. A., & Egeland, B. (2000) Attachment from infancy to early adulthood in a high-risk sample: Continuity, discontinuity, and their correlates. Hild Development, 71(3), 695-702.