Biodiversity Conservation in Our Watersheds

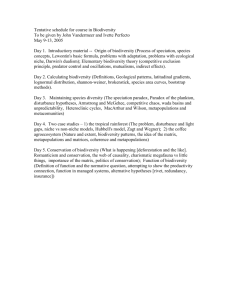

advertisement