Final Report - Partnership Africa Canada

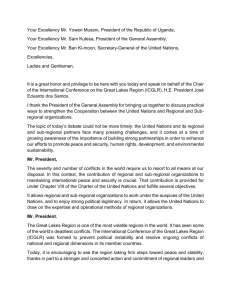

advertisement