(2) Needs, Capabilities and Rights

advertisement

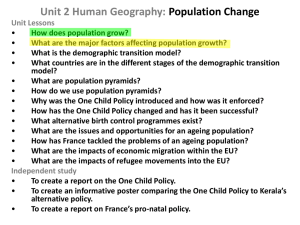

Needs, Capabilities and Rights -Looking for potential for emancipation Elisabeth Perioli Bjørnstøl Course: Human Rights and Development: Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Theory and Practices. HUMR 5701 1 Introduction There has been a shift in international development thinking from a main focus on nations and economic growth to more focus on non-economic issues and on human beings as proper referent objects of development. This shift can be seen most clearly in the introduction of the human development agenda by the UNDP in the early 1990’s. Human development has been influenced by several different approaches to development. The basic needs approach, the capability approach and most recently by views about human rights and development. While all these approaches share the view that lives of human beings ought to be the appropriate focus of development and that economic growth is not enough, they differ in their views on what else is needed in order to live a decent life. This in turn leads to different ideas about how the development process should proceed, on goals of development and ultimately thus on how success of the development process can and should be evaluated. This essay will deal with the relationship between these development approaches from the perspective of Critical Security Studies (CSS). CSS argues that since there are no objective notions of human well being and ‘the good’, the goal of theoretical enquiry into such issues must be to first make explicit the positions these notions derive from and then to seek to construct new and better possibilities by looking for unfulfilled emancipatory potential within such positions. The ultimate goal of this essay will thus be to evaluate the different approaches to development and on the basis of the emancipatory potential they promise and will argue that only an approach based on human rights can promise such potential. First the essay discusses International Relations (IR) theory to argue that Critical Security Studies is the most suitable theory for evaluating the different development approaches. Second, the essay describes the basic needs and capability approaches and then compares them in order to evaluate which approach promises most potential for emancipation. After a brief description of human rights, the essay goes on to discuss the relationship between human rights and the capability approach. The example of human rights based approaches to development is used to show how the emancipatory potential of human rights law can be transferred to the development process. 2 International Relations theory and development issues Traditional theories of IR have paid little attention to emancipatory potentials of individuals in global politics and to possibilities for constructing better future possibilities for people and the communities they live in. Understandings of how international politics work and how policy makers should act have for long been dominated by two theoretical perspectives; realism and liberalism. Both theories view global politics as concerned primarily with relations between states that must act anarchical world order without any overriding governing authority. Realism, has been, and still is, the dominant perspective in international relations and views states as the only legitimate actors in international affairs. Based on an assumption about the human nature of people being selfish, realists view states as driven by self interest and a quest for power. Trust between states is thus not possible and the only rational choice is therefore to try to accumulate military power on the expense of other states in order to enhance own security. Any cooperation is just seen as alliances of convenience, not ways of creating more security for all states. Liberalism shares some of realism’s assumptions about the anarchical nature of the world order, but argues that states are not the only actors in world politics. States must compete with other actors like international institutions and economic actors, and military threats are thus not seen as the only threats to state security. Based on an assumption of human nature as essentially good, a rational option for states according to liberalism is to participate in international cooperation among states in order to create more stable security structures. Anarchy can thus be somewhat ‘tamed’ according to proponents of liberalism. While differing in their views on possibilities for stable security, both perspectives also share many common assumptions. Both perspectives see states (and organisations in the case of liberalism) as the main referent object of international politics, not individuals. Both perspectives view military threats (in addition to economic threats in the case of liberalism) as posing the most urgent threat to the state, poverty is not considered a threat at all. Both perspectives also share foundational assumptions about the existence of a human nature, although differing although differing somewhat in their views on the content of such an alleged nature. Both theories thus also share assumptions about the ability of international actors to make rational choices, although they differ in their views on what the motivations for such choices are. (Hough, 2005, p 1-6) 3 Thomas and Wilkin argue that when realists and liberalists show interest in development it is often more a reflection of perceived threats from terrorism, migration and drug trafficking. They also argue that interests in economy often has little to do with poverty issues but much more to do with issues that are perceived as economic threats to the north like financial crisis etc. (Thomas and Wilkins, p245-246). The alternative focus, of course, would be to look at the different threats to human lives and human freedom in the South, and to look for ways of ensuring a more just world order. One such alternative focus, the Critical Security Studies theory (CSS), is considered both a “widener” and “deepener” of the security concept. Not only have proponents of CSS tried to widen the scope of the security concept to include other threats than military threats, they have also deepened their list of referent objects to include human beings and communities in order to reflect who it is that are actually experiencing feelings of insecurity. (Hough, 2004, p.8-10). Proponents of Critical Security Studies are thus concerned with all types of threats to human well being. In contrast to the orthodox theories CSS argue that these theories and their assumptions about which actors that are important, what threats are urgent and what choices that are rational are subjective and based more on the interests and ideas of policy makers and proponents of these theories than on any objective facts or truths about human nature. CSS, in contrast, can be considered a critical social constructivist theory advocating that there are no objective notions of security and human well being. All such notions derive from particular political or theoretical positions. Knowing this then, the goal must be to make explicit such positions in order to construct new and better possibilities by looking for unfulfilled potential in already existing notions and practices. (Booth 2005 10-17). Booth argues that the notion of emancipation should be an appropriate goal for international politics. Since everybody, everywhere can experience hope and has a notion of a possibility for betterment, they will therefore attempt to recognise and realise better possibilities and change over time. Emancipation is understood as the: ‘freeing of individuals and groups from physical and human constraints that stop them from doing what they would otherwise choose to do’ (Booth in Wyn Jones, 1999, p. 319), the ‘freeing of individuals and groups from structural and contingent human wrongs’ (Booth, 2005, p12). Emancipation is a practical 4 goal to construct something new out of situations that seem possible in the particular context and hence not just a critique of the existing situation. While an idea of possible betterment seems to exist everywhere there can naturally not be an ultimate truth of emancipation or how it will happen because it changes from context to context. Booth also argues that emancipation is a dynamic concept because it indicates the process of betterment, not a fixed end result. In addition to an idea about possible betterment then, emancipation also entails committed agency to construct new possibilities (Booth, 1999, p 41-46). In order to free people from physical and human constraints, both protection and empowerment is needed in the process of betterment. The basic needs approach Many have argued that in order to achieve justice it is not enough to just focus on the utility of economic growth and the advantages this might bring to people. In addition it is necessary to provide minimum resources for people to be able to function as human beings. Some philosophers, like Rawls, argue that the goal of a just society must be to promote the just distribution of primary resources, or what he calls ‘primary goods’. The ‘primary goods’ he argues, are goods that all rational individuals would require in order to carry out their lives as they plan to do. The list includes, but is not limited to, the following: liberties, opportunities, powers, wealth and income and the social basis of self respect, freedom of movement and free choice of occupation. This list could then be used as a criterion for evaluation, measuring how people are doing according to the list. (Rawls in Nussbaum pp 39-40) A ‘basic needs’ approach to development first emerged in opposition to the sole focus on modernisation after the Second World War. Organisations like the International Labour Organisation (ILO) and the World Bank developed a framework for basic needs and the focus in the 1960’s and 1970’s was on money incomes and how it could satisfy basic material needs. This period was followed by liberalisation and increased focus on economic growth and a belief that the market, competition and free trade would lead to a automatic trickle down effect on ordinary people in the 1980’s.(Desmond Mcneill: 275-279) While there is still faith in the market among many people, the large structural adjustment programmes of the IMF and World Bank in the 1980’s failed and the trend since the beginning of the 1990’s has been a refocusing on the human beings in development through the introduction of the human 5 development agenda. The first Human Development Report that came out in 1990 was drafted by Mahbub ul Haq who was a proponent of the ‘basic needs’ approach. The drafting committee consisted of adherents to both the ‘basic needs’ and capability approaches. The ‘basic needs’ approach has therefore formed an integrated part of the human development agenda from the start and many international organisations still use the concept actively in their work. (Stewart p 12-15) The focus of the ‘basic needs’ approach is on the basic minimum material needs of people and the goods and services like food, shelter, health services, education etc that people need to live a decent life. The assumption is that money income and social income give people choices to choose the kinds of basic goods and services that will lead to a decent life (Stewart p 9-12). The Capability Approach The capability approach was first advocated by economist Amartya Sen and later the philosopher Martha Nussbaum has also become a prominent advocate for the approach. In addition to a need for a provision of minimum resources in order for people to be able to function as human beings Sen has proposed that human freedoms are needed as well. Sen introduces capability and functionings as the most suitable criteria to evaluate how people are fairing in the development process. Functionings, he contends, reflect what a person may value doing or being. A person’s capability is all the various combinations of functionings that are feasible for that person to achieve. Capability is a type of freedom: ‘the substantive freedom to achieve alternative functioning combinations (or, less formally put, the freedom to achieve various lifestyles)’ (Sen, 1999, p75). Another way to put this is that functionings is what a person manages to be or to do, while capabilities are the real opportunities and choices that are available to that person. Evaluating realised functions would give information about what a person does, while evaluating capabilities would give information about what a person is free to do. It is ultimately this last information that the capability approach wishes to evaluate. (Sen, 1999, p 75-76) Sen does not specify a list of capabilities because he doesn’t want to purport a biased notion of ‘the good’, but Nussbaum has put forward a list of what she calls ‘the necessary basis for pursuing their good life’ (Nussbaum, p 43). She argues that this list is not based on human 6 nature, but on a summarization of empirical findings of cross cultural inquiry. The list includes: Life; Bodily health; Bodily integrity; Senses, imagination, and thought; Emotions; Being able to form a conception of the good and to engage in critical reflection about the planning of one’s life; Affiliation in regards to friendship and to respect; Other species; Play and lastly: Control over one’s environment, both political and material. (Nussbaum, pp 44-46) Nussbaum defines capabilities as entitlements and also distinguishes between three levels/ types of capabilities: Basic capabilities, Internal capabilities and combined capabilities in order to map out different influences on the functioning of a capability. Basic capability she explains as the innate equipment of individuals that is necessary for developing internal and combined capabilities. For example the capability for practical reasoning. By internal capabilities she means that each person must have the sufficient internal conditions for exercising the function. For example the internal capability to speak freely. Combined capabilities is the internal capabilities combined with favourable external conditions for the exercise of the function. If a person is not allowed to speak freely, she would only have the internal capability to do so but not the combined capability to actually use it. (Nussbaum p49) While Sen primarily advocates the capability approach as a tool to evaluate how people are doing Nussbaum goes further. Her stated goal is that the list of capabilities should also guide public policy and figure in constitutions or play the role of a constitutional guarantee. (Nussbaum p31) As with the Basic needs approach, the capability approach has influenced the human development agenda heavily. Amartya Sen was one of the members of the first drafting group in 1990 and more and more attention has been given to the capability approach in comparison to the basic needs approach over the years The capability approach has also heavily influenced the emergence and use of the human security concept in the UN. 7 Basic needs versus capabilities The main differences between the needs based approach and the capability approach seem to be as follows: While the capability approach advocate that people should be both beneficiaries and agents of development through entitlements to development, the basic needs approach reduces people in the development process to beneficiaries of development. While the capability approach values the importance of freedoms in the development process, the basic needs approach focus mostly on resources, i.e. goods and services. While the capability approach advocates that the goal of development must be to increase people’s choices, the goal of a needs based approach will be to increase goods and services. Also rights thinkers have argued for the necessity to cover basic minimums. Henry Shue advocate what he calls basic rights; ‘social guarantees against actual and threatened deprivation of at least some basic needs’ (Shue p18) and argues that rights are basic only if the enjoyment of them are necessary for enjoying all other rights. They are the rights that nobody should be allowed to sink below. He identifies three such groups of basic rights: security rights-pertaining to physical security and subsistence rights pertaining to minimal economic security or subsistence like food, shelter, minimal healthcare etc in order to have a decent chance to live a normal life. In addition he advocates some liberties, like participation and freedom of physical movement.( Shue, 1996, p 19-82). While the basic rights approach is close to the basic needs approach in its focus on basic minimums, it also goes further in 2 important ways; by actually advocating some liberties as basic minimums and by advocating that such basic minimums should be entitlements that can be claimed and thus connected to corresponding obligations of the state. While the idea of entitlements in Shue’s approach would have some emancipatory value, such a narrow focus on basic minimums makes it unlikely that people could actually have hope of the empowerment needed to better their own situation. This is even truer for the basic needs approach. Since such basic minimum approaches are more concerned with protection than empowerment, the emancipatory possibilities seem small compared to the capability approach that goes one step further by adding concerns with a larger set of freedoms to the development agenda. Although Nussbaum refers to her list of capabilities as basic, it seems clear that this 8 list goes well beyond such basic minimums since she for example includes capabilities relating to play. Further, Sen convincingly argues that since individuals vary greatly in their need for resources and ability to convert resources into valuable functionings a list of only resources may actually reinforce inequalities. Resources, he argues is thus not a good metric to measure who is better and worse off. (Nussbaum, 40-41) In practice, it is important to remember that the lines between the needs based approach and the capability approach may become somewhat more blurred in the implementation of the human development agenda. Nussbaum argues that; ‘the most illuminating way of thinking about the capabilities approach is that it is an account of the space within which we make comparisons between individuals and across nations as to how well we are doing’ (Nussbaum p 36). It seems difficult to ignore however that the Human Development Index (HDI) created to measure human development does not measure freedoms and uses mostly resource metrics to evaluate development. Indeed a Human Freedom Index (HFI) based on six civil and political freedoms was launched in 1991 but it was not successful and only lasted for a couple of years. While the capability approach, with a focus on both protection and empowerment, promises more potential of emancipation than the basic needs approach it thus also has some practical problems. In the next sections problems concerning the capability approach will be highlighted by comparing capabilities with human rights. Before that however, it is necessary to give a brief description of human rights. Human Rights Theories about rights of citizens have existed in western philosophy since Aristotle and has influenced many philosophers and indeed revolutions in Europe and the US. Much of the older literature on rights have made foundational claims, grounding rights in a common human nature, in a deity etc and has thus rightly been criticised as foundational. Theories about rights have also influenced ideas about human rights and the codification of those ideas into what is today known as human rights law. Since the end of the Cold War human rights law has increasingly inspired approaches to human well being in other areas than law, for example in international trade and production (fair trade and corporate social responsibility) and in development processes (the human rights based approach to development). 9 Legal codification of human rights started with the 1948 UN Declaration of Human Rights and continued in the later 1966 UN Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the 1966 UN Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR). The first represented aspirations, while the two latter are considered legally binding on states that have ratified these covenants. Later other legally binding international instruments have appeared in the UN; the conventions on racial discrimination, discrimination against women, prevention of torture, rights of children and rights of migrant workers and their families. The two covenants and these five conventions make up the core of international human rights law. In addition comes all the writing, observations and comments from different committees, commissions, independent experts etc that work with human rights in the UN. In addition the UN is continuously considering including other issues into international human rights law and various non binding declarations aimed at protecting different vulnerable groups or concerned with specific rights have been passed by the UN General Assembly, thus human rights law is not fixed; rights are in the process of being codified into law and are hotly debated in that process, new additions are likely to appear in the future and rights already codified into international law are continually reinterpreted and debated. Apart from the purely legal use of human rights, human rights are often used as moral and political tools. Human rights are invoked as protest against abuses, inequality and lack of necessary resources for physical existence regardless of whether they are codified in national law or whether they have achieved status as international law. Hence activists in China may refer to civil and political rights although their government has not yet ratified the ICCPR, or indigenous groups may talk about indigenous rights although a declaration on indigenous peoples have not been adopted by the UN General Assembly yet. The idea of human rights empowers people morally regardless of whether they are legal rights or not and this is a valuable additional meaning of human rights. Increasingly human rights law concerns have been linked to practical development approaches. In the last ten years a human rights based approach to development has emerged among development donors and in 2000 this approach was also included into the human development agenda through the 2000 Human Development Report. Before looking more 10 closely at this approach it is necessary to examine the relationship between capabilities and human rights. Capabilities versus human rights Nussbaum discusses the relationship between capabilities and human rights in an extensive way. She does not refer to a human rights based approach to development, instead she bases her discussion largely on the language of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. She argues that human rights are viewed either as legal entitlements that can be immediately justifiable in courts or as guiding non-justiciable aspirational principles that all branches of government should keep in mind as general propositions (Nussbaum p 47). She points to some important problematic issues concerning human rights like the grounding of human rights in a human nature and argues that because of such unclarity in the language of rights, the language of capabilities should be used instead. Human rights, like human development she claims, are rooted in the concept of capabilities and functionings. (Nussbaum p 26-29) She goes on to say that expressing rights in terms of capabilities would show us better that what is involved in securing a right is usually a lot more than putting it down on paper as can be seen in for example notions such as de facto and de jure unequality (Nussbaum p 55). Analysing material rights in terms of capabilities she argues would enable us to understand a rationale for spending unequal amounts of money on the disadvantaged, or creating special procedures to assist their transition to full capability, i.e. affirmative action strategies (Nussbaum pp 57-58). Concepts of universality, indivisibility, interdependence and interrelation are often ritualised rhetoric in her view but they acquire practical significance in the context of human capabilities (Nussbaum pp 46-47). According to Nussbaum the language of rights only play four important roles in public discourse (Nussbaum p 58-60): The language of rights can serve as a reminder that all people have justified urgent claims to certain urgent basic treatment quite close to the idea about basic capabilities like in the sentence: ‘A has a right to have the basic political liberties secured to her by her government’. At the state level, when talking about rights guaranteed by the state, the language of rights has strong normative resonance because it places much emphasis on the fundamental importance and basic role of rights. 11 The language of rights has value because of the emphasis on people’s choice and autonomy. It emphasises that what one ought to think of as benchmarks are people’s autonomous choices to avail themselves of certain opportunities, not only the functionings. In the areas where there is still disagreement about the proper analysis of right talkwhere claims of utility, resources and capabilities are still being worked out-the language of rights preserves a sense of the terrain of agreement, while continued deliberation about the proper type of analysis at the more specific level is carried out. In evaluating Nussbaum’s view of the relationship between capability and rights it becomes necessary to point out a few critical issues: First it seems that she talks about human rights law in a rather narrow way without ever once referring to the two UN covenants and the five UN conventions on international human rights law or the writing, observations, comments and draft laws from different committees, commissions, independent experts etc that work with human rights in the UN. Second, viewing human rights as legal entitlements and/or non-justiciable guiding principles only in states that have ratified conventions also seem too narrow. Human rights should also be understood as moral and political tools invoked by people and organisations who experience hardships regardless of whether their governments have ratified any human rights conventions or not. The language of rights provide hope of betterment and potential for emancipation for many. Third, while there are certainly some important problematic issues concerning human rights theory like the foundational grounding in a human nature etc, this can surely be overcome within the human rights approach as well. It is certainly possible to advocate human rights and still agree with the view that there is no shared human nature or pure human essence and argue that therefore any universality of values cannot emerge from a common human nature. What then are human rights if they are not universal values? Although perhaps a bit premature, there is a case for arguing that human rights are on their way to becoming global instruments for emancipation and that that is the only way they can become universal. 12 Fourth, while the language of the capability approach does indeed explain the rationale of rights and the rationale for choosing affirmative action etc in a good way so too does the language of human rights. Where the capability approach would use the language of basic capability, internal capability and combined capabilities, human rights language will use concepts like human potential, rights and enjoyment. While the capability approach thus surely is a useful tool for talking about human rights, it is not absolutely necessary for the language of human rights, contrary to what Nussbaum seems to argue. Instead it is possible to turn the argument around and argue that the language of human rights is actually more useful to the capability approach than vice versa. For example in the capability approach there seems to be much focus on evaluative aspects and very little focus on implementation issues. How, exactly, are people supposed to achieve capability and functionings? While Nussbaum describe capabilities as entitlements and opens for the possibility of inclusion of basic capabilities in constitutions she does not, unfortunately, describe exactly how these entitlements are to be constitutionally guaranteed. In fact it is the possibility to claim rights and to hold duty bearers accountable that sets the human rights apart from capabilities and promise both the necessary protection and empowerment needed for emancipation. While Nussbaum discusses human rights in a narrow fashion, it would however also be interesting to try to compare the capability approach to the new human rights based approaches to development in order to evaluate whether the emancipatory potential of human rights can be transferred to the development field. Human Rights Based Approaches to Development A human rights based approach seems to have great potential for transforming development efforts. Unfortunately there has been no uniform international approach to human rights among development agencies so far, even though many have developed some sort of policies on human rights and development, for example the OHCHR, Unicef and Care International.1 According to Uvin, at least four levels of human rights integration can be distinguished among development agencies: At the lowest level of integration there has only been a 1 For an overview on development policies on human rights see Nyamu-Musembi and Cornwall, 2004, and Uvin, 2004 13 rhetorical incorporation of human rights terminology into the development discourse, while no real changes in approach has taken place. At the highest level a truly rights-based approach to development imply a holistic approach to development and social change where all agency mandates are redefined in human rights terms thereby mainstreaming human rights into all areas of development. (Uvin, 2004, p 47-50) Hansen and Sano have examined many of the new human rights-based approaches to development and conclude that at least the following principles should be included in a truly human rights based approach(Hansen and Sano p44-51 in Marks and Andreassen, 2006): The universality principle i.e. that all development programmes should have the objective of improving human rights. The indivisibility principle i.e. that the advancement of any right will depend on advancement of all other rights and no right should be pursued to the detriment of others. The accountability principle i.e. that rights holders should be transformed from passive recipients to empowered claim holders that can claim rights towards their legal duty holders and claim organisational accountability to development organisations-not only to outcomes, but also to processes of development The participation principle i.e. that people should be enabled to make decisions on issues that affect them The non-discrimination principle i.e. the demand that particular attention be given to access to public decision making by minorities or vulnerable groups. The empowerment principle i.e. to ensure freedoms and people’s capacity to claim and exercise their rights effectively In comparison to the capability approach it is possible to determine that a human rights based approach to development is much more comprehensive. This can be seen in particular in the use of the accountability principle. While the capability approach does not seem to ensure accountability at all, the human rights based approach to development goes even further than international human rights law by adding organisational accountability not only to the outcomes of development but also to the development process itself. Compared with other development approaches the human rights based approach to development seems to offer 14 better protection and more opportunities for empowerment. While there thus seems to be great emancipatory potential in the human rights based approach it is, however, important to remember that a promise of accountability is not the same as actual accountability. Without suitable mechanisms for redress nobody can be held accountable in the development process. Conclusion While the basic needs approach to development promises protection of people by aiming to provide basic minimum goods and services, the potential for emancipation is small since the basic needs approach does not also promise hopes for empowerment. The capability approach on the other hand offers hope of both protection and empowerment, but in reality it is difficult to see how such empowerment can be guaranteed without any accountability mechanisms. Human right laws, by introducing the notion of obligations, has the aim of ensuring real empowerment where people can become active agents in their own lives by holding duty bearers accountable. A new approach to development based on human rights offers better potential for protection and empowerment in development by promising an accountability principle that covers not only states, but also other development actors. It still remains to be seen whether this emancipatory potential of the human rights based approach to development will materialise! 15 Bibliography Andreassen, Bård Anders, The Human Rights and Development Nexus: From Rights Talk to Rights Practices in Banik, Dan (Ed), 2006, Poverty, Politics and Development: Interdisciplinary Perspectives, Fagbokforlaget, Bergen Booth, Ken (ed), 2005, Critical Security Studies and World Politics, Lynne Rienner, London Booth, Ken, Three Tyrannies in Dunne, Tim and Wheeler, Nicholas.J., 1999, Human Rights in Global Politics, Cambridge University Press Hough, Peter, 2005, Understanding Global Security, Routledge New York Kirkemann Hansen, Jakob, Sano, Hans-Otto, The Implications and Value Added of a Rights Based Approach in Andreassen, Bård. A., Marks, Stephen. P.(eds), 2006, Development as a Human Rigth, Legal, Political and Economic Dimensions, Harvard University Press, London McNeill, Desmond, Multilateral Institutions: A Critical Overview in Banik, Dan (ed), 2006, Poverty, Politics and Development: Interdisciplinary Perspectives, Fagbokforlaget, Bergen Nussbaum, Martha, Capabilities, Human Rights, and the Universal Declaration in Weston, Burns H. and Marks, Stephen. P., (eds) The Future of International Human Rights, Transnational Publishers, New York Nyamu-Musembi, C and Cornwall, A., 2004, ‘What is the “rights-based approach” all about? Perspectives from international development agencies’, IDS Working Paper 234, Institute for Development Studies, Sussex Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, 2004, Human Rights and Poverty Reduction: A conceptual Framework, UN Geneva and New York Sen, Amartya, 1999, Development as Freedom, Oxford University Press, Oxford Shue, Henry, 1996, Basic Rights, Subsistence, Affluence, and U.S. Foreign Policy, Second Edition, Princeton University Press, USA Stewart, Frances, 2004, Human Development as and alternative development paradigm, http://hdr.undp.org/docs/training/oxford/presentations/2004/topic_1 Thomas, Caroline and Wilkin, Peter, Still Waiting after all these Years: ‘The Third World’ on the Periphery of International Relations’. BJPIR: 2004 Vol 6, 241-258 Uvin, Peter, 2004, ‘Human Rights and Development,’ Kumarian Press Inc., USA Wyn Jones, Richard, 1999, Security, Strategy and Critical Theory, Boulder 16