Comprehensive Assessment of Spoken Language

advertisement

Hayward, Stewart, Phillips, Norris, & Lovell

Test Review: Comprehensive Assessment of Spoken Language (CASL)

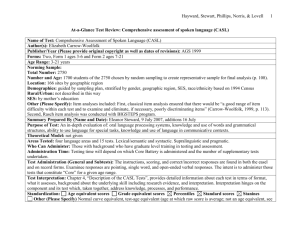

Name of Test: Comprehensive Assessment of Spoken Language (CASL)

Author(s): Elizabeth Carrow-Woolfolk

Publisher/Year: AGS 1999

Forms: two, Form 1 ages 3-6 and Form 2 ages 7-21

Age Range: 3 to 21 years

Norming Sample

Based on her theory of language, Carrow-Woolfolk explains in the acknowledgments that she began the process of developing this

test by dividing “language” into component parts of structure and processing; then further into item types which she felt would elicit

language behaviours reflecting competence and use. With draft test items, Carrow-Woolfolk conducted an initial tryout in one school

in Houston, TX. She states that this process of tryout offered information and insight into how useful (or not) the items were. Then

she expanded the pool to two school districts in a second tryout. The third tryout aimed to identify “special problem areas”.

Formal test development was initiated in 1992 when three pilot studies were conducted (1992-94). The pilot studies addressed item

selection and discrimination. These studies demonstrated that the Rhyming Words test did not show adequate increasing skill with

age increases. Additionally, two tests, Second-Order Comprehension and Non-Literal Language, were combined into one test, NonLiteral Language.

The process continued with three national tryouts (1995-1996) aimed at scoring criteria, administration time, item selection, and bias.

As a result, changes were made that included deletion of items that did not “meet the criteria for difficulty, discrimination, internal

consistency, model fit, or item bias” (Carrow-Woolfolk, 1999, p. 106).

Total Number: 2 750

Number and Age: 1700 students of the 2750 chosen by random sampling to create representative sample for final analysis p. 108

Location: 166 sites by geographic region

Demographics: guided by sampling plan, stratified by gender, geographic region, SES, race/ethnicity based on 1994 Census

Geographic: four major regions defined by US Census Bureau: Northeast, North Central, South, and West

Rural/Urban: not described in this way

SES: by mother’s education

1

Hayward, Stewart, Phillips, Norris, & Lovell

Other: Though not designated as a sample criterion, special education categories were represented in the standardization sample “in

approximately the same proportions that occur in the U.S. school population” (Carrow-Woolfolk, 1999, p. 111). Categories were:

specific learning disabilities, speech or language impairments, mental retardation, emotional disturbance, and other impairments.

Result indicated that totals are within 0.9 percentage points of the targets. As outlined in Table 7.15, percentages were compared to

U.S. population data from U.S. Dept. of Education.

The standardization process was extensive, clearly reflecting a commitment on the part of AGS to Carrow’s work. Tables in the

manual show representation by gender/age, geographic region/age, mother’s education level/age, race/age, race/mother’s education,

race/region, The resulting standardization sample was, “within 1 percentage point of the total target U.S. population percentage for

each region” (p. 108).

Coding and scoring procedures for the open-ended items were examined. Open-ended responses were analyzed when they appeared

to be idiosyncratic (p. 112).

Summary Prepared By (Name and Date): Eleanor Stewart 9 July 07 additions on 16 Jul

Test Description/Overview

The test kit consists of three easel test books, a norms book, an examiner’s manual, two record forms (Form 1 for ages 3 to 6 and

Form 2 for ages 7-21), and a nylon carrying tote. The drawings are in black and white.

The CASL is an oral language test that consists of 15 individual tests covering lexical/semantic, syntactic, supralinguistic, and

pragmatic aspects of language. Carrow-Woolfolk states that these tests examine oral language skills “that children and adolescents

need to become literate as well as to succeed in school and in the work environment” (p. 1).

The test manual is well-organized and written in an easy-to-read style that makes Carrow-Woolfolk’s theory and rationale easy to

read. A chapter is dedicated to Carrow’s Integrative Language Theory. Carrow-Woolfolk explains her theory of language

development which focuses on four components: lexical/semantic, syntactic, supralinguistic, and pragmatics around which the CASL

is framed. Carrow further details each by classifying categories as follows: lexical semantics, syntactic semantics, pragmatic

semantics, and supralinguistic semantics. She provides a rationale for the division into categories based on research (p. 11). Carrow

argues that assessment should target knowledge, processing (ie. listening comprehension and oral expression), and performance. In a

section addressing language disorder, Carrow explains that a good theory must also account for a breakdown in language. She points

2

Hayward, Stewart, Phillips, Norris, & Lovell

to the difficulties in defining the borders of language disorder as well as the difficulties attending to language difference (using an

interesting example of French Canada, p. 17).

Comment: I think that what Carrow is offering is more of a model than a theory. She is pulling together much of what we know about

language development and theorizing about a way to bring it all together in a working model with individual skill sets that can be

assessed though she argues for integration. Carrow’s use of the terms “content” and “form” alert us to the origins of her

theoretical perspective on language. In this, she is referring to models such as Bloom and Lahey, and to Chomsky’s theoretical work

(this last which she cites).

Purpose of Test:

Carrow-Woolfolk states that “The CASL provides an in-depth evaluation of:

1) the oral language processing systems of auditory comprehension, oral expression, and word retrieval,

2) the knowledge and use of words and grammatical structures of language,

3) the ability to use language for special tasks requiring higher level cognitive functions,

4) the knowledge and use of language in communicative contexts” (p. 1).

Further, the author states that CASL can be used to: identify language disorders, diagnose and intervene in spoken language, monitor

growth, and conduct research. In these last two, the author notes that the wide age range on which the test was standardized allows

for tracking children’s performance longitudinally. Of particular note to TELL, Carrow states, “Researchers can use the CASL to

explore the relationship between oral language processing skills and reading abilities” (p. 7).

Areas Tested: The manual provides a table (Table 1.2 on page 2) of the four language areas and 15 tests.

The four components and corresponding subtests are:

1. lexical/semantic: comprehension of basic concepts, antonyms, synonyms, sentence completion, and idiomatic language

2. syntactic: syntax construction, paragraph comprehension of syntax, grammatical morphemes, sentence comprehension of

syntax, grammaticality judgment

These first two components comprise the first level of analysis. Followed by:

3. supralinguistic: nonliteral language (figurative speech, indirect requests, sarcasm), meaning from context, inference, and

ambiguous sentences

4. pragmatic: pragmatic judgment

3

Hayward, Stewart, Phillips, Norris, & Lovell

Comments from the Buros reviewer: Meaning from context not clear as “it is claimed that all information needed to solve these

problems is provided in the sentences, which is difficult to evaluate” (Snyder & Stutman, 2003, p. 217). Also, regarding Pragmatic

Judgment, “it is difficult to evaluate these assertions. There is no discussion of what factors might lead an examinee to do well on the

Pragmatic component, yet still exhibit difficulties with {communicative intent} outside of the testing situation” (p. 218). “This

reviewer is not convinced that the Basic Concepts, Paragraph Comprehension, Synonyms, and Sentence Comprehension rely on

receptive aspects more than other tests in the battery” (p. 218).

Areas Tested:

Oral Language

Vocabulary

Listening

Lexical

Syntactic

Grammar

Narratives

Supralinguistic

Other (Please Specify)

Who can Administer: Those with background in language, education, or psychological testing who have graduate level training in

testing and assessment may administer this test. The range of potential examiners includes: neuropsychologists, school psychologists,

educational diagnosticians, speech-language pathologists, learning disability specialists, reading specialists, and resource room

teachers.

Administration Time:

Testing time will depend on which Core Battery is administered and the number of supplementary tests undertaken. Table 1.6 (p. 8)

provides administration time estimates for each test based on the standardization sample. Based on time estimates in Table 1.6,

administration time could be as short as17 minutes for three Core tests at age 3 years to 3 years, 5 months or as long as 59 minutes

for five Core tests at 8 years to 8 years, 11 months.

Comment: A useful table summarizing all the tests with ages, basal and ceiling rules, processing skill, structure category,

description, and examples is found on the AGS website.

Test Administration (General and Subtests):

Test administration is straightforward although the examiner needs to be very familiar with all the test materials and the record form.

The instructions, scoring, and correct/incorrect responses are found in both the easel and on record forms. The basal and ceiling rules

4

Hayward, Stewart, Phillips, Norris, & Lovell

5

are stated at the beginning of each test. Examinee responses are pointing, single word, and open-ended verbal responses. Not all tests

are administered to all age groups. The intent is to administer those tests that constitute “Core” for a given age range. The same test

may be Supplementary to a different age group. For example, at age 5 years to 6 years, 11 months, core tests include antonyms,

syntax construction, paragraph comprehension, and pragmatic judgment but basic concepts and sentence completion are

supplementary at this age range.

Comment: I think that a clinician needs to be very familiar with this test prior to administration as the print layout on the record

form is busy and instructions are detailed. Clinicians need to be careful to have the appropriate booklet and to observe somewhat

varying ceiling rules.

Comment: The manual states, “The basal and ceiling rules were constructed with the goal of maintaining high reliability while

minimizing testing time” (p. 119). This statement indicates to me that the author acknowledges how difficult it is to administer a test

that takes a long time to reach ceiling.

Comment: The Buros reviewer points to scoring difficulties that may be related to the elevated level of linguistic complexity required

for “responses approach[ing]naturalistic communication that creates increasing scoring difficulty. This, however, may be

unavoidable in an instrument that seeks to assess the full range of linguistic functioning.” Also, the reviewer notes scoring difficulties

with the core vs. supplementary structure of the test in which it is sometimes onerous to look up standard scores to determine

whether to continue with supplementary testing (Snyder & Stutman, 2003, p. 220). Finally, the reviewer states that “A computer

program for scoring that could be used in tandem with the testing would also ease this difficulty” (p. 220).

Test Interpretation:

Chapter 4, “Description of the CASL Tests”, provides detailed information about each test in terms of format, what it assesses,

background about the underlying skill including research evidence, and interpretation. Interpretation hinges on the component and its

test which, taken together, address knowledge, processes, and performance.

Chapter 6, “Determination and Interpretation of Normative Score,” describes the standardized scores, the steps taken to complete

comparisons using standard scores, and provides two examples of student’s completed CASL results.

Standardization:

Age equivalent scores

Grade equivalent scores

Percentiles

Standard scores

Stanines

Other (Please Specify) Normal curve equivalent, test-age equivalent (age at which raw score is average; not an age equivalent,

Hayward, Stewart, Phillips, Norris, & Lovell

see p.90). Core Composites, Category Indexes and Processing Index Standard Scores.

Comment: Each of these obtained scores is defined and explained in the manual. I find this useful both as a review and as a way of

communicating to others what the scores mean and how to use them.

Reliability:

The manual describes in detail the extensive reliability testing that was undertaken. For each, data are provided based on sample

characteristics.

Internal consistency of items: How: Using Rasch split-half method, a Rasch ability estimate was calculated and then correlated and

reported by age group for all 15 tests. Overall, the reliabilities were high.

Also, reliabilities were reported for the Core Composite for each age band and the five Index scores, calculated using Guilford’s

formula. The Core reliabilities were in .90s and the Indexes ranged from .85 to .96.

Standard Error of Measurement (SEM)/confidence intervals: computed for 12 age groups using split-half reliabilities. Overall, SEMs

ranged from low 3.6 to high 9.0.

Test-retest: 148 randomly selected students in three age groups: 5 years to 6 years, 11 months; 8 years to 10 years, 11 months; and

14 years to 16 years, 11 months were retested. The interval was 7 to 109 days, with a “median interval” of 6 weeks. “Almost all

retesting was done by the same examiner who had administered that CASL the first time” (Carrow-Woolfolk, 1999, p. 123).

Characteristics of the sample were provided. Coefficients (corrected and uncorrected) for Core tests, Supplemental Tests, and

Indexes were presented in table form by age range with SD. Ranges: .65 (synonyms)-.95 for tests, .92-.93 for Core Composites, and

.88-.96 for Indexes.

Inter-rater: no information

Other: none

Validity

Content: Carrow’s detailed description of the constructs and the tests provides the basis for content validity. She based the tasks on

previous research and the theoretical design she developed. Item analyses included: First, classical item analysis ensured that there

would be “a good range of item difficulty within each test and to examine and eliminate, if necessary, poorly discriminating items”

6

Hayward, Stewart, Phillips, Norris, & Lovell

(p. 113). Second, Rasch item analysis was conducted with the BIGSTEPS program.

Criterion Prediction Validity: Studies compared scores from four language tests and one cognitive test: TACL-R, OWLS, PPVTIII/EVT, and K-BIT. Each correlation produced comparisons with counterbalanced samples of slightly different size and age groups.

Results indicate:

high correlations with PPVT-III on lexical/semantic and receptive index score, and the same for EVT with lexical/semantic

and expressive index score,

highest correlation with OWLS Oral Composite with a range of correlations that reflect different content and format,

correlations distinguish between language and cognitive on K-BIT, and

high correlations with receptive tasks on TACL-R.

Construct Identification Validity: The Author provides information on: developmental progression of scores, intercorrelations of

CASL tests, and “factor structure of the category and processing indexes” (Carrow-Woolfolk, 1999, p. 126).

Progression of scores across age ranges.

Intercorrelation coefficients range from .30 to .79 for 6 age groups. There are “moderate correlations among tests, low enough

to support the interpretation that each test is measuring something unique but high enough to support their combination to

produce the Core Composite and Index scores” (p. 125).

Factor analyses are detailed for ages 3-4, 5-6, and 7-21 years. A one factor model for ages 3-4 and 5-6 demonstrated Model

Fit Statistics. A three factor Model was used for groups in the 7-21 year range. The author summarizes the results: “There

appears to be a trend that as the examinees get older, the fit of the data to the model gets better (chi-square decreases steadily

and p increases). There also appears to be a trend that the factor correlations decrease as the examinees’ age increases. Both

of these trends are consistent with the language theory on which the CASL is based, which predicts that as children grow

older, the linguistic structure changes from general to specific. Thus a simpler and more general one-factor model fits the data

better for younger children, while a more complex and specific three-factor model fits the data better for adolescents and

young adults. For the intermediate groups (7-10 and 11-12), the hypothesized models fits the data only moderately well,

indicating that these age groups are in the transitional stage of language development” (p. 130).

Differential Item Functioning: Comment: This information has been covered by developmental progression of scores but I do not

see any other reference or statistical analysis using the term DIF.

7

Hayward, Stewart, Phillips, Norris, & Lovell

Other (Please Specify): Beginning on page 137, clinical validity with eight different clinical groups matched for gender,

race/ethnicity, SES and region was detailed with this standardization sample: speech impairment n= 50, language delay n=50,

language impairment n=42, mental retardation n=44, learning disability (reading) two separate age samples n=50 and n=30,

emotional disturbance n=31, and hearing impairment n=7.

Comment: To their credit, AGS acknowledges that the very small sample of children with hearing impairment limits interpretation

for that group. They note difficulty in obtaining a homogenous sample of hearing impaired children. However, they point out that the

finding of performance one standard deviation below the mean is consistent with other studies reporting on hearing impaired

children and published tests (Carrow-Woolfolk, 1999, p. 146). For clinicians working with children with hearing impairments, it is

disappointing to find, once again, they are left searching for means of objectively testing the skills of hearing impaired children.

Comment: The Buros reviewer states “Additional information would also be useful in supporting the internal validity of the CASL”

(Snyder & Stutman, 2003, p. 218).

Summary/Conclusions/Observations:

Although Carrow is aiming for an integrative test, I still feel that with the CASL that we are breaking down into smaller parts for

examination and then attempting to draw it all together in the end using composite profiling. This may be a function of the author’s

orientation to cognitive information processing models. In this sense, the CASL still feels like an old style test to me (in contrast to

Test of Narrative Language (TNL) or the Preschool Language Assessment Instrument-PLAI).

While I think it is commendable to address the pragmatic aspect of language, I am not sure that the particular tasks are adequate. It

is difficult to access this aspect of communication in contrived interactions.

I found the discussion of memory elucidating as I have wondered what role memory played in some of the test reviewed so far. See

also, CELF-4 for RAN and discussion of memory in relation to language.

Clinical/Diagnostic Usefulness:

The CASL is an extensive diagnostic test. For that reason, it is unlikely that clinicians would use it unless there are specific

diagnostic questions. More likely, they would select subtests that target specific skills. If only certain subtests were selected, then of

course, we would need to be careful about use of psychometrics.

8

Hayward, Stewart, Phillips, Norris, & Lovell

9

There have been few tests that address adolescent language so this test is a bonus to those who follow children from elementary to

junior high and beyond, particularly when young adults prepare for work.

Elizabeth Carrow-Woolfolk is a familiar author in speech-language pathology having developed the widely used Test of Auditory

Comprehension of Language (TACL-3). The test is often referred to as “the Carrow” and is most often used in test batteries to

quickly assess morphosyntactic language aspects. Carrow-Woolfolk is also the author of the Oral (OWLS), (CAVAT), and (CELI).

References

Bloom, L. and Lahey, M. (1978). Language development and language disorders. NY: Wiley.

Carrow-Woolfolk, E. (1999). Comprehensive assessment of spoken language (CASL). Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service.

Chomsky, N. (1980). Rules and representations. New York: Columbia University Press.

Snyder, K. A., & Stutman, G. (2003). Review of the Comprehensive Assessment of Spoken Language. In B.S. Plake, J.C. Impara, and

R.A. Spies (Eds.), The fifteenth mental measurements yearbook (pp. 216-220). Lincoln, NE: Buros Institute of Mental

Measurements.

U.S. Department of Education. (1996). Eighteenth annual report to Congress on the implementation of the individuals with disabilities

education act. Washington, DC: Author.

To cite this document:

Hayward, D. V., Stewart, G. E., Phillips, L. M., Norris, S. P., & Lovell, M. A. (2008). Test review: Comprehensive assessment of

spoken language (CASL). Language, Phonological Awareness, and Reading Test Directory (pp. 1-9). Edmonton, AB:

Canadian Centre for Research on Literacy. Retrieved [insert date] from http://www.uofaweb.ualberta.ca/elementaryed/ccrl.cfm