How to Introduce Direct Quotations in Formal

advertisement

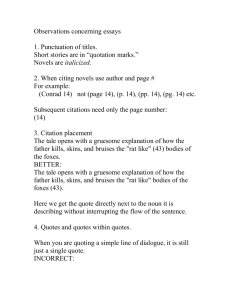

How to Introduce Direct Quotations in Formal Expository Papers When you directly quote a source in your paper, you must make the words of your quote match grammatically with your own introductory words. In other words (hee), the words of the quotation, when combined with your own words, must make sense as a single, grammatically correct sentence. Most students have trouble with this at first. Typically, students try to make quotations function as a single part of speech, or a single part of a sentence: “Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow/ Creeps in this petty pace from day to day” is the beginning of Macbeth’s last soliloquy. (subject) The last soliloquy is about “Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow/ Creeps in this petty pace from day to day,” and Macbeth speaks it sadly after learning that his wife has died. (object of a preposition???) In Macbeth’s last soliloquy, he speaks about death and “Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow” and how it comes as a result of the inevitable movement of time “creeps in this petty pace from day to day.” (abstract noun, WHAT??!!! Respectively) But quotations don’t function singularly in a sentence; they merely extend your own words in some way beneficial to your explanation. So let’s look at three models that you can use to introduce your quotations from now on. First rule of thumb: Place your quotations at the ends of your sentences. This will eliminate most problems with direct quotation. Then, learn to use the following introductions to your quotes. 1. The Elementary Method If you know of no other way to introduce a direct quotation, you merely need to remember your first reading books. You begin your quote by announcing the speaker or the writer of the quote and then placing a comma before the quotation mark and the capital letter that begins the quote. Remember? Ted said, “See Spot Run.” Sally said, “Run, Spot, Run!” Spot said, “Ruff, ruff, ruff.” Translate these simple sentences into the world of analysis you are now living in, replace the “said” of yesteryear with the SAT-esque words of the post-PSAT world you are now entering, and you have this same template for introducing your quotes: Macbeth states, “Life is but a walking shadow.” Macbeth asserts, “It is a tale told by an idiot” (Shakespeare 210). Buckley writes, “We have not seen the end of the recession yet.” One note: don’t introduce your quote in this elementary manner by implying some complicated connection to previous sentences. In other words, don’t use the following construction: Chaucer shows this when he states, “In short, he was a good man” (23). Chaucer isn’t really showing anything here. He is simply stating something, right? Stick with the simple mention of the name and one other word in this method of introducing quotes. 2. The Intermediate Method, a.k.a. The Colon Connection (YUCK!) In this second, more mature style of introducing your quotes, you present a complete sentence that logically explains the idea behind your quote. After this introductory independent clause, you place a colon, and then you finish the with a complete sentence of direct quotation that illustrates your explanation: William Buckley disagrees with the optimism of the current administration: “We have not seen the end of the recession yet” (34). Note the two complete sentences, interrupted quickly with an economical colon. Also note that your sentence of introduction explains the idea behind your quote. It does not merely reword the quote, right? William Buckley feels that the recession is not over yet: “We have not seen the end of the recession yet.” This is merely redundant and repetitive, saying the same thing over and over again ad nauseam. 3.The Adult Method You finally come to the method most professional writers use: we arrive at the fruition of life, if your life revolves around direct quotation. You introduce your quotes by including them nonchalantly in your own sentences. Were it not for the quotation marks setting off the quote, you would not be able to tell where your own words ended and the words of your quote began. Yes, the quotation marks, at last, function for their true purpose: they indicate where your words end and where the words of a source begin. Buckley feels that this weak time in the economy “will last well into 2007.” Take out the quotation marks, and the sentence makes perfect grammatical sense, although, technically, it also demonstrates plagiarism: Buckley feels that this weak time in the economy will last well into 2002. Caveats *With each of these methods of introducing quotes, you are saying something up front that helps explain the use of the quote. So it makes sense, does it not, that you couldn’t possibly quote back-to-back, one quote ending with a quote mark, and then a quote mark immediately following to signal another quote. At the very least, you would have an introduction to the second quote immediately following the end of the first quote. *When you are quoting a single word, make sure to use the adult method. Don’t quote like this: The author uses words like “grey,” “black,” and “Night” to suggest evil in the world. Instead write something like this: The author says the “night” is “grey” and that the world is “black”; these words imply evil. *When you need to cite the author of a quote, do so in proper MLA format: Shakespeare reminds us of our “disgrace with fortune and men’s eyes” (13). We must beware of the “disgrace with fortune and men’s eyes” (Shakespeare 13). Note that the citation comes immediately after the last quotation mark. If, when you master direct quotation, you decide to move into the risky and liberal world of quoting in the middle of your sentences— and remember that if you do this the terrorists will win—you still put the citation immediately after the last quotation mark. *DO not use ellipsis at the beginning or the ending of a direct quotation. Remember that ellipsis is used to indicate that you are skipping over portions of a text within your direct quotation. It’s not necessary to let your reader know that the beginning or the end of your quote is not the entire quote.