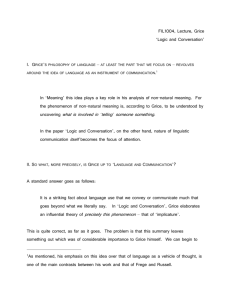

Grice paper Final Draft - Edinburgh Research Archive

advertisement