WAVETRAKING, or OUT OF NOWHERE

advertisement

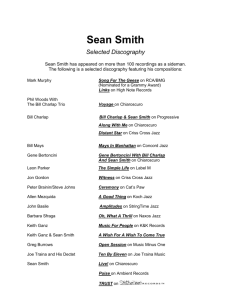

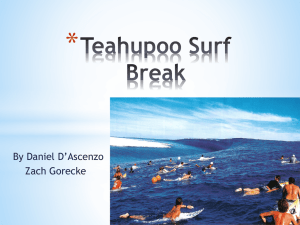

WAVETRAKING, or OUT OF NOWHERE The Surfline Story INTRODUCTION Surf forecasting is like the surfboard leash: it's an everyday part of our lives, yet it's changed our world almost beyond belief. In the past 20 years, since Surfline's 1985 debut, surfer behavior has been entirely transformed as a result of this craft -- part science and part art, part surf story and part pure data. A Surfline.com subscriber can now, if he or she chooses, log on at home and check swell predictions five days in advance, not just in the backyard, but anywhere on the planet. Forecasting changes thousands of working weeks; helps you choose which boards to take to GLand; gets you out of bed on mornings you'd otherwise have missed; keeps you tuned to ocean movements that once were utter mysteries. But what we know now as an essential part of our daily surfing lives mightn't even exist if it weren't for a young Seal Beach surfer by the name of Sean Collins, whose natural curiosity led him to ask, back in the 1970s: "Where the HELL did that last south swell come from? And how can I tell when the next one's gonna show?" THE NEW ZEALANDERS It was all about the souths, for two big reasons. The first had to do with their mythic status in southern Californian surf lore. A big, long-interval southwest groundswell, arriving seemingly sourcelessly, had everyone in awe. These swells would show up, out of nowhere, last four or five days, and sometimes go back to back, two or three in a row, stringing into weeks of waves. Rumor would connect these swells with supposed hurricanes far off Mexico, or perhaps even earthquakes, but knowledgeable surfer-meteorologists knew they must have origins deep in the Southern Hemisphere, somewhere between South America and New Zealand. In 1975 Surfer magazine did a cover story called "Monster From New Zealand", which marked the term's entry into the argot. The second reason is simpler: the souths came in summer, which meant they affected way more people's surfing lives than the winter northwests. (Southern Hemisphere swells, according to Surfline records, are more than merely a summertime frolic -- they're SoCal's most consistent surf source, running over 250 days a year.) They also happened to coincide with Sean's own personal obsession with Central Baja right-hand pointbreaks. In November 1969, while crewing his father's sailboat along this coast, he surfed Scorpion Bay during a late season south for the first time, all by himself. Sean's memory of it is ultra-vivid: "I just walked around that entire point, thinking 'Oh my God! Look at this!'" It was one of those classic surfing epiphanies, a surf session that changed the course of his life. His pursuit of information regarding the "New Zealanders" -- and his eventual understanding of the oceanography involved in a swell's 6000-mile journey from storm to coastline -- led to his first public forecast: March 25, 1985, when Surfline gave the whole of southern California a week's advance warning of an overhead south – and it landed on the button. (Sean was so sure of the swell; in fact, he had the company launch over a week early. Needless to say, Surfline's history would've been very different had this first swell not been nailed.) But none of this knowledge came easy, not in a world before the Internet or fax machines. If Sean wanted to predict the surf, he soon realized, if he wanted to Know When To Go, he'd have to figure the whole thing out for himself. TAPPING THE SOURCE Technology was the first hurdle. After all, it wasn't as if the Los Angeles evening TV news was about to start showing Southern Hemisphere atmospheric pressure charts. If you were going to find out what was happening, you needed to tap some less-than-obvious information sources. This led Sean to the Nagrafax machine. Designed for open-ocean sailors, the Nagrafax is basically a short-wave radio receiver built to convert short-wave-broadcast weather data to a print facsimile. Sean talked his Dad into buying one for their sailboat sometime in 1981, but it didn't stay onboard too long. He still keeps it under his desk at Surfline's offices, right under his computer screen. It comes in a metal casing with a hinged clip-on lid, and is accompanied by the receiving device and whatever kind of aerial you can cobble up to fit. (In Sean's case, this is a 100-foot roll of copper wire.) The Nagrafax uses aluminized paper; a spark triggered by the short-wave tone would burn the image in. On the inside of the lid is a printed schedule of satellite broadcast times, letting you know when the weather maps will be coming downstream. The Southern Hemisphere maps are due in from an obscure weather station in Christchurch, New Zealand at around 1 a.m. Southern California time, so Sean, back then before any of the surf forecast thing was publicly available or even particularly discussed, would set his alarm, get up, switch on the Nagrafax, and pull those maps out of the ether. Sean would take it to Baja on hurricane runs, hanging the copper wire antenna out over the cactus for better reception, and the Federales would open up the metal box and freak, thinking this was some kind of CIA mission. Other than that, Sean had his sources. The Navy had a polar satellite called GEOSAT, for instance, which took updates of the Southern Hemisphere; he had to draw maps off it by hand, and guess the winds by the look of the cloud patterns. He's held onto some of these maps, too; they look like cave drawings, with their hand sketched arrows and lines over a vague and cloudy background. "You'd get ship reports occasionally too," he says. "But it wasn't all put together. Really, you could only guess." CHROSTOWSKI BREAKS THE CODE Weather maps were fine and good. But any surfer who's tried to match map with swell will know it's a game fraught with uncertainty. For one thing, a map won't tell you the true wind-strengths involved; for another, they can't give you any clues as to the nature of any groundswells the wind might have created. For that kind of information, there was only one reliable source: the buoys. Wave buoys were up in the 1960s -- oddly enough, the US military had been into surf forecasting for decades, since the Second World War Pacific campaign, when they'd discovered that island landings depended on the swell -- but if you were a mere member of the public, there was no practical way of accessing the data. Therefore, Sean turned himself into a sort of human wave buoy. He'd sit on the roof of the family house in Surfside and fill up a spiral bound notebook with observations on the nature of the waves hitting the nearby breakwall. He'd spend an hour taking notes, then chart it all out: wave heights, intervals, the lot. In the end he had a rule of sorts – if there were more waves with a 16-second period, and there were waves with a longer period, the swell was still rising; if not, the swell was stable or dropping. In the 1980s you could get hold of the buoy info if you direct-dialed a government computer and downloaded manually, computer-to-computer -- a kind of mini-Net. But this was raw data, which made little sense to someone trying to read for approaching swells. Sean could do it on paper, transcribing the data into columns and puzzling it out, but the technique took hours, sometimes almost all day. In surfing terms, it was like trying to paddle out using only one hand. Jon Chrostowski lent the other hand. Actually, Jon gave Sean the equivalent of a jetski. Jon was a tennis buddy and computer expert who wrote him a program that broke the buoy data down to spectral detail -- in other words, you were able to view not just the wave heights but the swell intervals as well. Jon did this on an IBM XT, one of the earliest MS-DOS desktops. Sean at the time was handwriting his forecasts; he had no idea how to type. "But I did know how to read the buoys." Suddenly he could study forerunner swells -- the early part of a swell, long interval and often smaller in height than any prevalent chop or sea state action, but a certain indicator of a bigger swell on the way. Eventually the TOGA weather buoys off Peru kicked in and he was able to see a southern hemi swell on its journey across the Pacific, after it'd been created, but anywhere from four to seven days before the SoCal impact. It was a hidden source at the time, and Sean is not afraid to admit to holding some hidden sources to this day. "We combine data now with a few sources that we will not reveal," he says, almost but not quite grinning. "That would be like giving guns to the Indians." REPORTING IN "I can stand on the pier at Huntington and tell you what the surf's like from the Ranch to San Diego." Thus spake a renowned old-school surf sage, several years ago. These words in hindsight are pure fantasy. Southern California's odd positioning behind its chain of Channel Islands, coupled with a maze of offshore canyons and a broad continental shelf, means that almost any swell will look different from region to region – sometimes from beach to beach. Nobody could do it without understanding swell intervals and wave shadows at a level Sean was only just beginning to grasp. He says: "I was figuring out this puzzle that nobody knew." If you're a hardcore surfer, it's hard not to feel a tingle at the thought of this project. What a task! To become a local knowledge expert, not just on a beach or two, but on a whole coastline. Sean first twigged to the sheer power of surf information when he researched the LA County lifeguard phone-in surf condition reports, and found they were getting over a million calls a year. But the lifeguards were notorious liars – they'd say it was tiny when in fact it'd be going off, just to cover for their local buddies. This was the early 1980s, and Sean -- married, with a new baby, and painfully aware that waiting tables and taking surf photos wasn't going to make the cut -- was determined to turn his obsessive hobby into an actual career. Before forecasting, reporting paid the bills. Surfline's founders Jerry Arnold, Craig Masuoka and Dave Wilk began with a surf report phone-in line that Sean was determined to make accurate. He drafted NSSA members up and down the coast, kids he'd met on Baja surf runs, to report their local areas, and made sure he trained them thoroughly. The reports gave Sean his first insights into swell interval, and how dramatically these affected the unevenly swell-shadowed SoCal coastline. To counteract wayward reporters, Sean went out and found payphones near the surf spots, then set up a schedule whereby he'd call the phones; the reporters had to answer, and he'd know for sure they'd checked the waves. Over time Surfline had a solid crew: Huntington's Rockin' Fig worked for him as well as for KROQ; there was Peter Brouillet, Janice Aragon, Eric "Bird" Huffman. "We even employed street people," he claims. "One guy who used to live on a park bench up around Venice Beach, John Hans, he was always sooo on it. He would be pissed when we called his payphone late! 'I've been up since 6:10 am!' he'd snap." The result of all this groundwork became clearer as Surfline blossomed and forecasting developed into Sean's mainstay focus. He was able to let beach users know not just that a swell was coming, but exactly when they might expect it to show on their local beach, based on the swell interval and direction that was most likely to evade island shadowing. The extent to which nobody believed any of this at first became very obvious after Sean, having spotted an approaching northwest with a lot of energy in the 20-second interval range, let a wellknown LA TV weatherman, Dr George, tell the viewers a couple of days out. Dr George got a nogo from his usual sources, who said it'd never happen, and as a result he recanted Sean's forecast the next night. The following day, boom! Long-interval-swell areas were hit by the biggest surf in ages. Sean's specialized knowledge eventually led him to split from Surfline and set up his own operation, Wave-Trak. In 1990 the two companies merged, putting the biggest share of the surfreport business in one house. The scene was set. THE CUTTING EDGE Almost by accident, what Sean was doing put him right there at the cutting edge of the sport. This was the overarching story of the 1980s and '90s: modern surfing shaking off the black-magic superstitions of its early years and engaging with tactile reality. Designers like Al Merrick, Rusty Preisendorfer, Pat Rawson and Simon Anderson compiled measurements, refined curves, and employed precise cutting machines. Brilliant yet eminently practical surfers like Kelly Slater and Laird Hamilton pushed the aquatic limits using their minds and hands as much as their souls. In this context, surf forecasting -- getting your head around the idea that surf came not out of nowhere, but out of SOMEWHERE -- was an idea whose time had come. At one level, it was a vital part of the puzzle for hundreds of thousands of surfers whose lives simply didn't allow them to spend all day everyday at the beach. On another level, it suited the increasing velocity of surfing's media/pro-surfer nexus. Photography and video was hotter than ever, its needs more refined, pro surfers' time more at a premium. Thus Surfline found itself making calls, some of them verging on epic. In July 1996, for instance, Sean saw a huge cutoff low-pressure system forming within 500 miles of Tahiti. At the time, the extraordinary waterman Mike Stewart was on the island shooting video at the as-yet-unknown Teahupo'o. "I called up Sean," said Mike later, " just to find out what was gonna happen and he said there's a HUGE one on the way. I said unreal, you know, 10 or 15 feet. He said no, you know, like Waimea big." For the next six days, guided by Sean, Mike chased the swell from Tahiti all the way to Alaska via Maalaea, the Wedge, and a central California secret spot -- a mission that remains unduplicated before or since. Mike returned from his final session near Yakutat, stunned at what he described as "the amount of energy that's out there. That's what I picked up by traveling with it -- that this thing is so incredibly powerful." This was one in a chain of Mission Forecasts harking back to late 1986, when Sean and his longtime colleague, Surfing magazine's Larry "Flame" Moore, teamed up to nail Killer's, off Todos Santos near Ensenada. It was the first photo trip to that now renowned surf zone, and the sight of Tom Curren, Dave Parmenter and Mike Parsons cascading down the massive wave faces helped ignite an equally massive resurgence in big-wave riding -- a resurgence we see today in the North Pacific every winter, as dozens of tow teams pursue surf in excess of 50 feet. It was all just preparation, though, for the really Big One: Project Neptune. For over a decade, Sean and Flame had conjectured on the chances of riding a big northwest swell on Cortes Bank, a submerged reef 100 miles offshore, outside the Channel Islands' swell block. In early January 2001, their chance finally came. Sean was able to predict the swell, but the weather? Cortes is in mid-ocean, and any wind would ruin it … and 48 hours before The Day, it was blowing an ugly northwest. "I could see these computer models clearing up," says Sean. "It felt right to me. I gave Flame a go, but I was a nervous wreck. I was dying all night. In the morning I heard nothing from anyone, so I ended up going surfing. Then about 2pm I got a message on the answer phone from Larry, screaming: 'Dude! You nailed it! It was huge and glassy!' I remember driving home really relieved." Sixty-foot waves in mid-ocean…the surf trip that christened the century ... and at least partly because "it felt right"! Even within all the science, the data, there was still room for mystery. TO TELL OR NOT TO TELL? A lot of Sean's work has been in developing ways of saying things that all surfers -- not just a few – could clearly understand. This was critical, especially in Surfline's early days, when 976-SURF and 1-800-SURFLINE were its only source of income, and you only got one pass to explain everything to a caller. In the surf forecast game, customers are "tough… They blame you for everything, including their divorce, everything. You need to be cautious -- but you still need to be making a call." One of the big issues was calling wave heights. Here he encountered a classic piece of 1970s Surf Mysticism: from coast to coast, you couldn't tell what people meant by "three feet". In Hawaii, "three feet" was taller than your surfboard and might even snap it in half. In Florida, "three feet" meant you could stand up on your board. In California, it was somewhere in between, but might even mean different things depending on whether you lived in San Clemente, San Diego or Santa Cruz. "People didn't have a broad language for what surf looked like," says Sean. "I thought we should call surf by the face height, but some others thought we'd make it sound overhyped." They ended up with the now-standard body height measure: knee-high, waist-high, chest to shoulder high, overhead, double overhead, and so forth. In the same way, Surfline developed a certain caution in predicting a swell's arrival. Sean might be reasonably sure of something setting in on a Thursday afternoon, for instance; the forecast would say Friday, "with maybe some early signs beforehand". This kept a certain faith with the eagle-eyed surfers who checked their spots several times a day -- after all, if you were on a swell yourself, you couldn't attack the forecast for giving you a free afternoon. But in other ways, his work brought Surfline into direct conflict with surfing's old school. Telling people – strangers! anyone! – about surf on the way! To some surfers, this was heresy. "Just by the nature of what I do, some people say, 'Oh, you're selling out'," says Sean. "I'm super sensitive about some areas." Over time and through many ups and downs, Surfline developed a policy: anywhere there's a camera, any mainstream spot visible from the road, then it's open to surf reports. But in the forecasting, Surfline doesn't mention ANY spots by name. Instead, its forecasts focus on generalized regions -- North Orange County, for example, or South San Diego -- while throwing in hints that an educated surfer can follow with ease. "Deepwater spots", "spots with a good south exposure"; such terms leave at least a little of the work to the viewer or listener. "They need to pay their dues just like everybody else," says Sean, showing a bit of the old school side himself. THE NET EXPLOSION Where were you in 1985, anyway? Born yet? Unbelievably, for the first decade of Surfline's existence, there was effectively no such thing as the World Wide Web. When it came into wide public use through the early to mid-1990s, surf forecasting turned upside down. The first live camera, or "surf-cam" as they've become known to a generation of Net-savvy waveriders, was set up by Sean at Huntington Beach, for the 1996 US Open, using a closed circuit video security camera and a computer program called "Snap and Send". Every five minutes, the program would take a single frame from the camera record and upload it to whatever place you'd instructed it. In the surf-cam's case, it was to a slot in the newly minted Surfline site, and it ranks as the first live surf website update in history. (The same software was borrowed by the ASP's computer guru Mano Zuil, who used it later to do webcasts from WCT events around the globe.) In late 1996, streaming video technology arrived, and suddenly the Huntington camera was LIVE -- or all but live, with new images downloading every five seconds. You could see waves moving! For every kid who'd dreamed of being able to check the surf while you were stuck miles away at home or school or wherever … the dream was now completely real. Of course this brought its own headaches for the men behind the scenes. At Pipeline, Sean spent a week in Gerry Lopez's bathroom trying to figure out a glitch in the computer that ran the Pipe surf-cam. One silver lining of all this techno-craziness was an increase in the Surfline head forecaster's computer-savvy; he actually ended up learning how to build computers as a result. This was before Surfline could afford computer experts of its very own. So where was the money? Many surfers assumed Sean was growing rich, but it was anything but the case. Through the mid-1990s, as the World Wide Web grew and grew, the company was doing a lot of business, but it wasn't translating into profit. There was almost no money coming off the Internet site, even though it was scoring almost a half million unique visitors a month, cannibalizing the 1-900 phone-line income. After all … why call for surf reports if they were available online, free? Sean was plowing a lot of time and energy into educating Web newbies in the use of this medium, but precious little was coming back. Sometimes he had to fund payroll out of his own personal pocket. All that changed in a very short time in 1999, when Internet fever descended on surfing just as it had on almost every other form of human behavior at the time. Out of nowhere they came, just like a bombing New Zealander – first B.I.G., the backers of Bluetorch, then Hardcloud.com, then Swell.com, throwing money at something they all realized was the Killer App of the 21st surfing century. Sean was bemused, and then entertained by the seemingly mad-dollar offers. Then it dawned on him they might be serious. Swell.com won the battle, and while the dot-com boom turned bust shortly afterward, the cash injection gave Surfline's Killer App a shot at the next level. Namely, LOLA. LOLA By now, surfing was filled with amateur forecasters -- keen surfers who'd gone on-line and discovered things like the US Navy worldwide swell prediction maps, and the coastal offshore wave buoy readings. No longer were they couched in the indecipherable code of the shortwave '80s. Now they were as far away as the tap of a computer mouse. Surfline needed more, and the dot-com world gave it the chance. Back in the 1980s Sean had met a guy named Bill O'Reilly, a surfer and oceanographer who was pursuing a doctorate at Scripps in San Diego. Bill did a little work for Surfline for a while, but his real task, along with gaining a Ph.D, was a computer swell-modeling program called the Coastal Data Information Program -- CDIP. The program, funded by the Army Corps of Engineers, had a lot to do with swell shadowing for Southern California, which gave Sean and Bill a keen mutual interest. They stayed in occasional touch. In the late '90s, Sean visited Scripps to hear one of Bill's doctorate dissertations, and they got to talking about how cool it would be to develop a really excellent swell model for surfers – if only they had the cash. When Swell.com came along, Sean took Swell.com's financier, Florida surfer Jeff Berg, up to San Francisco, where O'Reilly had shifted base, to talk about it. The result? LOLA, in her basic form, was launched in 2001, after almost a year's development. In essence, LOLA is a meeting place for data: all the sources Sean's found to be effective for forecasting, from Wave Watch III to the NOGAPS atmospheric charts and many more, are pulled together and reformatted. Some tweaking is done to fit the forecasters' on-the-coastline experience, and there it is, on your premium membership screen: the most powerful information tool in modern surfing. "It's like this umbrella, with all these pieces underneath," says Sean. While it runs, LOLA – like a thoroughbred racing car -- is constantly re-tuning itself; Sean plans to plug in new satellite data that will allow her to re-correct as swells hit in real time. In future, she'll only grow more accurate. TODAY, TOMORROW, AND…. So what's Surfline's current status? If one of the team was doing a daily report it might read something like: "Light winds, head high and still glassy, should keep pumping all afternoon." The company is a tight ship, with many of its original surf reporters still in place and a forecast staff steadily growing their unique craft. Sean pays tribute to the likes of Chris Borg, Kevin Noonan, George Mason, Adam Wright, Kevin Wallis, Mark Willis and Micah Sklut, and to former East Coast whiz Vic Morris. "Nobody really makes a lot of money," says Sean, "but the lifestyle's incredible." He insists that while meteorological training helps, the true key to a good forecaster is his or her sense of surf. "It's the emotional involvement that keeps you connected … if you interact with actual waves you have a feel for it that's impossible to duplicate." The future? Sean's forecast looks something like this: a continual upgrading of LOLA; expanding wireless information for cell network users; and host of new features in ’05 for the website. In the meantime, he watches for big souths, and – like the rest of us – waits for surf, waits to make the call again. "My goal in this had nothing to do with money," he says. "My goal was if there was going to be good waves, I'd know about it."