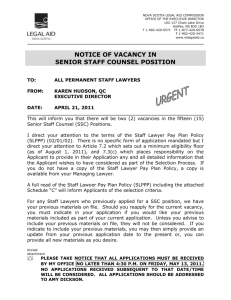

PART 1: THE NATURE OF RULES OF PROFESSIONAL CONDUCT

advertisement