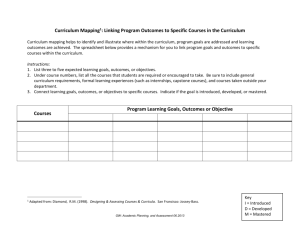

Assessment definitions

advertisement

Moving SoTL Projects Forward: Applying what you already know and do to SoTL - Methodologies and Literature Searches Alix Darden, Alix-Darden@ouhsc.edu This workshop will focus on the basics needed to begin ones’ own research and scholarship in teaching and learning. Participants will be engaged in a hands-on minds-on workshop and are encouraged to bring questions, materials and/or SOTL projects they are engaged in or are thinking about. It is assumed that participants have a question in mind or in progress. The main focus of the workshop will be on finding appropriate methodologies and relevant literature. Other topics that will be covered include human subject considerations, finding mentors and collaborators and qualitative and quantitative assessment of data. Assessment definitions Function of assessment Diagnostic Assessment – The gathering of information at the outset of a course or program of study to provide information for both the teacher and student about students’ prior understanding. Diagnostic assessment can help to maximize learning by: 1) revealing what students already know and don’t know about a subject so that the teacher can focus lessons appropriately; 2) revealing what students already know and don’t know about a subject so that the student can focus their study appropriately; 3) exposing misunderstandings and misconceptions in prior knowledge; and 4) making it clearer to students the type of understanding that the teacher values for this subject. This type of assessment, coupled with summative assessment, is used to determine the value-added of an educational experience. Formative Assessment - The gathering of information about student learning-during the progression of a course or program and usually repeatedly-to improve the learning of those students. Formative assessment supports student learning through constructive feedback by: 1) diagnosing student difficulties; 2) measuring improvement over time; and/or 3) providing information to inform students about how to improve their learning. Example: reading the first lab reports of a class to assess whether some or all students in the group need a lesson on how to make them succinct and informative. Summative Assessment - The gathering of information at the conclusion of a course, program, or undergraduate career to improve learning or to meet accountability demands. Ideally, summative assessment reflects the culmination of the scaffolding process of learning provided by formative assessment throughout the course. When used for improvement, impacts the next cohort of students taking the course or program. Examples: examining student final exams in a course to see if certain specific areas of the curriculum were understood less well than others; analyzing senior projects for the ability to integrate across disciplines. 1 Assessment targets Assessment of Individuals, Assessment of Assignments, Assessment of Courses, Assessment of Programs, Assessment of Institutions. Assessment at a point in time v. longitudinal assessment Assessment tools and techniques Qualitative Assessment - Collects data that does not lend itself to quantitative methods but rather to interpretive criteria Quantitative Assessment - Collects data that can be analyzed using quantitative methods, i.e. numbers, statistical analysis Validity – A measure of how well an assessment relates to what students are expected to have learned. A valid assessment measures what it is supposed to measure and not some peripheral features. Reliability – A measure of the constancy of scoring outcomes over time or over many evaluators. A test is considered reliable if the same answers produce the same score no matter when and how the scoring is done. Direct Assessment of Learning - Gathers evidence, based on student performance, which demonstrates the learning itself. Can be value added, related to standards, qualitative or quantitative, embedded or not, using local or external criteria. Examples: most classroom testing for grades is direct assessment (in this instance within the confines of a course), as is the evaluation of a research paper in terms of the discriminating use of sources. The latter example could assess learning accomplished within a single course or, if part of a senior requirement, could also assess cumulative learning. Indirect Assessment of Learning - Gathers reflection about the learning or secondary evidence of its existence. Example: a student survey about whether a course or program helped develop a greater sensitivity to issues of diversity. Embedded Assessment - A means of gathering information about student learning that is built into and a natural part of the teaching-learning process. Often uses for assessment purposes classroom assignments that are evaluated to assign students a grade. Can assess individual student performance or aggregate the information to provide information about the course or program; can be formative or summative, quantitative or qualitative. 2 Assessment Methodologies – You need to be very clear as to your research objective – What specifically do you want to measure/evaluate? Is your assessment method a valid and reliable measurement of what you want to measure? Assessing learning Objective tests Pre/Post tests Rubrics Classroom assignments Skills competency Student Portfolios Audio taping Video taping Surveys – student self-report Types of questions Likert scale questions – rate 1-7, from best to worst. Can be statistically analyzed Open-ended questions – “code” the written answers Types of surveys satisfaction values, attitudes, expectations confidence motivation learning Assessing learning development Bloom’s taxonomy SOLO taxonomy Focus Groups/interviews Audio taping Observations Video taping Think alouds Triangulation/ Mixed-methodology 3 Bibliography On-Line Searching To find on-line SoTL resources, Google “SoTL” or “Your discipline”+SoTL ERIC – Educational Resources Information Center - Search a bibliographic database of more than 1.1 million citations on education topics going back to 1966. http://www.eric.ed.gov/ Assessment resources Georgetown University’s Visible Knowledge Project toolkit for analyzing qualitative data. http://cndls.georgetown.edu/crossroads/vkp/resources/kits/qualitativedata/index.htm NSF 2002 user-friendly Handbook for Project Evaluation http://www.nsf.gov/pubs/2002/nsf02057/start.htm Rubistar – a free tool to help a teacher make quality rubrics http://rubistar.4teachers.org/index.php Angelo, T.A. and K. P. Cross. 1993. Classroom Assessment Techniques. 2nd ed. JosseyBass, 427 pp. Paperback. Beckman, TJ and Cook DA. 2007. Developing Scholarly projects in education: a primer for medical teachers. Medical Teacher, 29:210-218. Biggs, J. B. and Collis, K.F. 1982. Evaluating the quality of learning: the SOLO taxonomy. Academic Press, New York. Bloom, B. S. 1956. Taxonomy of educational objectives, handbook I: The cognitive domain. David McKay Co. Inc., New York. Brookhart, SM. 1999.The art and Science of Classroom Assessment: The missing part of Pedagogy. ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Report (Vol 27, No. 1)Washinton DC:The George Washinton University, Graduate School of Education and Human Development. Dunn, L., Morgan, C., O’Reilly, M. and Parry, S. 2004. The student assessment handbook: new directions in traditional and online assessment. Routledge Falmer, New York. Epstein, RM. 2008. Assessment in Medical Education. N Eng J Med. 356(4):387-396. Geisler, C.A. 2003. Analyzing Streams of Language: Twelve Steps to the Systematic Coding of Text, Talk, and Other Verbal Data (Paperback) - expensive brand new, but can get used copies on line Huba, M. E., and Freed, J. E., 2000, Learner-centered assessment on college campuses shifting the focus from teaching to learning, Allyn and Bacon, Boston, MA. Krueger, R. A., and Casey, M. A., 2000, Focus groups: a practical guide for applied research, Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, Calif. Stevens, D.D. and Levi, A.J. 2005, Introduction to Rubrics: An assessment tool to save grading time, convey effective feedback, and promote student learning. Stylus Publishers, Inc., Sterling, VA. Walvoord, B. E. F., and Anderson, V. J., 1998, Effective grading a tool for learning and assessment, Jossey-Bass Publishers, San Francisco, CA. 4 Development of the Learner Baxter Margolda, MB. 1999. Creating Contexts for Learning and Self-Authorship: Constructive-Developmental Pedagogy. Vanderbilt University Press. Bransford, JD, Brown, AL and Cocking, RR, eds. 2000. How People Learn: Brain, Mind, Experience and School. National Academy Press, Washington DC. Nelson, C 1999. On The Persistence Of Unicorns: The Tradeoff Between Content And Critical Thinking Revisited. In B. A. Pescosolido and R.Aminzade, eds. The Social Worlds of Higher Education. Pine Forge Press. Application of Perry in the classroom. Perry, WG[1970] 1998. Forms of Intellectual and Ethical Development in the College Years, A Scheme. New introduction by Lee Knefelkamp. Jossey-Bass. Some classic SoTL studies R. R. Hake. 1998. Interactive-engagement vs. traditional methods: A six- thousandstudent survey of mechanics test data for introductory physics courses. American Journal of Physics 66, 64. Classic study showing the impact of active learning using the mechanics concept inventory as pre/post tests. P. U. Treisman. 1992. Studying Students Studying Calculus: A Look at the Lives of Minority Mathematics Students in College. College Mathematics Journal 23: 362-72. [UC Berkely, Workshop Calculus, African-American D/F/W rate from 60 percent to 4 percent.] See also R. E. Fullilove and P. U. Treisman. 1990. Mathematics Achievement Among African American Undergraduates at the University of California, Berkeley: An Evaluation of the Mathematics Workshop Program. Journal of Negro Education 59: 46378. M. D. Sundberg and M. L. Dini. 1993. Science majors vs. nonmajors: Is there a difference? Journal of College Science Teaching Mar./Apr. 1993:299-304. [Multiple sections and instructors. Both courses taught with traditional pedagogy, but with different intensities of ‘coverage.’ “The most surprising, in fact shocking, result of our study was that the majors completing their course did not perform significantly better than the corresponding cohort of nonmajors.” [Note: Less wasn't more, without pedagogical change, but more wasn't more either—and student attitudes suffered.] J. Russell, W. D. Hendricson, and R. J. Herbert. 1984. Effects of lecture information density on medical student achievement. Journal of Medical Education 59:881-89. Three different lectures on the same subject. 90 percent of the sentences in the high-density lecture disseminated new information as did 70 percent in the medium and 50 percent in the low. Remaining time used for restating, highlighting significance, more examples, and relating the material to the student's prior experience. Students randomly distributed into the 3 groups (no significant differences in prior GPA or on knowledge base pretest). Students in low treatment learned and retained lecture information better. Here less is more. 5 Active Learning Allen, D and Tanner, K. Infusing active learning into the large-enrollment biology class: Seven strategies, from the simple to complex. Cell Biology Education. 4:262-268. 2006. http://www.lifescied.org/cgi/content/full/4/4/262 Angelo, TA, KP Cross: Classroom assessment techniques: a handbook for college teachers, 2nd edn. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 1993. Bean, JC: Engaging Ideas. The Professors Guide to Integrating Writing, Critical Thinking, and Active Learning in the Classroom. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 2001. Bess, JL: Teaching alone, teaching together transforming the structure of teams for teaching, 1st edn. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2000. Bonwell, CC and JA Eison: Active Learning: Crating Excitement in the Classroom. Washington DC, The George Washington University; 1991. Bowman, S. Preventing Death by Lecture. 2005. Bowperson Publishing Co. Glenbrook, NV. Bransford, JD, AL Brown, RR Cocking, eds: How People Learn. Brain, Mind, Experience and School. Washington DC, National Academy Press; 2000. Available free online at: http://www.nap.edu. Davis, BG: Tools for teaching, 1st edn. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 1993. Ebert-May, D, C Brewer, S Allred: Innovation in Large Lectures--Teaching for Active Learning. Bioscience 1997, 47:601-607. Fink, L. Dee: Creating Significant Learning Experiences. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2003. Ghosh, R: The Challenges of Teaching Large Numbers of Students in General Education Laboratory Classes Involving Many Graduate Student Assistants. Bioscene 1999, 25:7-11. Knight, JK and Wood, WB: Teaching more by lecturing less. Cell Biology Education. 2005. 4:298-310. http://www.lifescied.org/cgi/content/full/4/4/298 MacGregor, J: Strategies for energizing large classes from small groups to learning communities. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2000. McKeachie, WJ, G Gibbs: McKeachie's teaching tips strategies, research, and theory for college and university teachers, 10th edn. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Co; 1999. Redish, EF, JM Saul, RN Steinberg: Student Expectations in Introductory Physics. 2000. Stanley, CS, ME Porter: Engaging large classes: strategies and techniques for college faculty. Bolton, Mass.: Anker Pub. Co.; 2002. Zull, JE: The Art of Changing the Brain. Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing, 2002. 6