Writing an Essay

advertisement

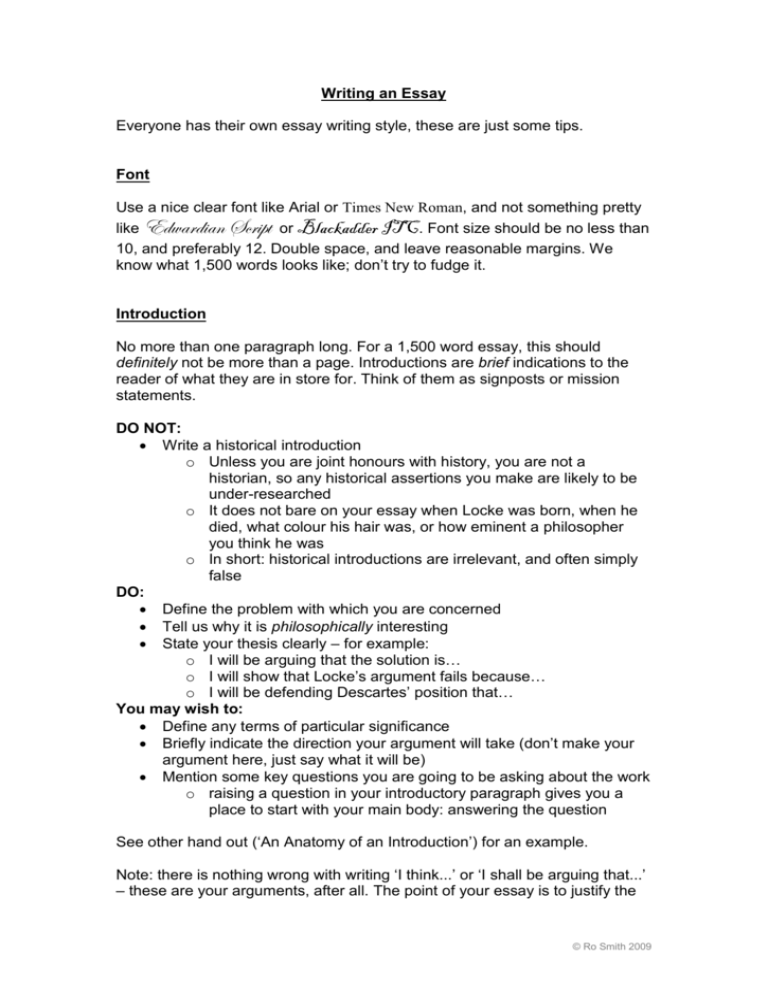

Writing an Essay Everyone has their own essay writing style, these are just some tips. Font Use a nice clear font like Arial or Times New Roman, and not something pretty like Edwardian Script or Blackadder ITC. Font size should be no less than 10, and preferably 12. Double space, and leave reasonable margins. We know what 1,500 words looks like; don’t try to fudge it. Introduction No more than one paragraph long. For a 1,500 word essay, this should definitely not be more than a page. Introductions are brief indications to the reader of what they are in store for. Think of them as signposts or mission statements. DO NOT: Write a historical introduction o Unless you are joint honours with history, you are not a historian, so any historical assertions you make are likely to be under-researched o It does not bare on your essay when Locke was born, when he died, what colour his hair was, or how eminent a philosopher you think he was o In short: historical introductions are irrelevant, and often simply false DO: Define the problem with which you are concerned Tell us why it is philosophically interesting State your thesis clearly – for example: o I will be arguing that the solution is… o I will show that Locke’s argument fails because… o I will be defending Descartes’ position that… You may wish to: Define any terms of particular significance Briefly indicate the direction your argument will take (don’t make your argument here, just say what it will be) Mention some key questions you are going to be asking about the work o raising a question in your introductory paragraph gives you a place to start with your main body: answering the question See other hand out (‘An Anatomy of an Introduction’) for an example. Note: there is nothing wrong with writing ‘I think...’ or ‘I shall be arguing that...’ – these are your arguments, after all. The point of your essay is to justify the © Ro Smith 2009 claims of your introduction. Main Body: Outline one argument in response to the problem o E.g. Locke’s argument for the existence of God Analyse and critique o What are the premises? o What is the conclusion? o Does the conclusion follow on from the premises? o Are all the premises true? o Are there any hidden premises/assumptions that are needed to make the conclusion follow form the premises? o Even if the premises are true, and the conclusion follows from them, does the argument prove what the philosopher told us they set out to do? Demonstrate an understanding of the dialectic: discussion structured by argument and counter-argument. You can do this by: o Giving a counter-argument or counter-example offered by another philosopher you have read, or o Thinking of your own counter-example, then o Thinking about how the philosopher might respond Could you reply to that? If so, is there anything else he might say in response? Demonstrating the dialectic helps you to explore the issue thoroughly from all angles. This will refine your critical abilities (you may discover that your criticisms weren’t as good as you thought they were, or that there is a better criticism you didn’t see at first) and allow you to demonstrate a more thorough knowledge and understanding of the text The process of the dialectic should lead you naturally to your conclusion, which should be whichever position comes out on top. If you find that the argumentative process seems to lead to a conclusion you find unappetising, you should either: a) step back and think a bit more about what it is that seems wrong to you; or b) change your position If you can’t do either of these things, then your conclusion will not be supported by your argument Conclusion: Briefly summarise the main reasons (which you will have argued for) in support of your conclusion, and make sure you state clearly exactly what that conclusion is. Your conclusion, like your introduction, should be no more than one paragraph long, and should not contain any further argument. Include a word count at the bottom of your final page. © Ro Smith 2009 A Note on Referencing: Two main ways of referencing Harvard style/in-text referencing Footnotes In our department, we favour in-text referencing: Name (date: page number), or (Name date: page number) E.g. Descartes (2006: 8) writes that: ‘Eggs are nice’ Or: It has been argued that: ‘Eggs are nice’ (Descartes 2006: 8) Or: Descartes (2006: 8) gives an argument for the niceness of eggs, which runs as follows… These are brief references that direct the reader to your bibliography. Bibliography entries should look like this: Author Surname, Author Forename or Initials1 (date of publication), ‘Title of Chapter/Article’ (page numbers of chapter/article), Title of Book, name(s) of any editors and/or translators followed by (trans.), (ed.), or (eds) as appropriate, Place of Publication: Publisher E.g. Kant, I. (1978), ‘Introduction: I. Of the Difference Between Pure and Empirical Knowledge’ (pp. 25-26), Critique of Pure Reason, J. M . D. Micklejohn (trans.), New York: Dutton The name should be as it appears on the cover/title page of the book – if you know Kant’s first name was Immanuel, but the title page says ‘I. Kant’ then list it in your bibliography as: ‘Kant, I.’ not ‘Kant, Immanuel’. Note also that footnotes can be used to provide useful bits of information that are extraneous to your main argument. However, these should be included in your word count, and should be used sparingly. 1 © Ro Smith 2009