the impact of social history on the

advertisement

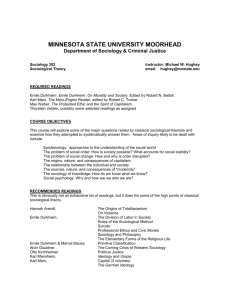

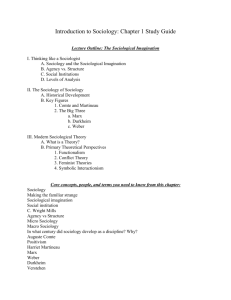

Rationale: Our proposed text will illustrate how the variety of theoretical traditions significant to American sociology emerged from, and implicitly in response to, specific historical contexts. We feel that this approach is important because both undergraduate and graduate students are offered an enormous body of theoretical information in their theory courses and elsewhere in the curriculum, but they generally have little idea about why certain theorists or topics were considered important in their day or have an abiding value to the discipline. By focusing on the historical context in which theorists lived and responded to, we believe that students will acquire a more grounded understanding of theory. Part I of the text focuses on the founding figures of sociology and highlights the social problems that they each grappled with. As is evident, American sociology emerged out of European roots, and it is those origins that concern us in this section. Chapter 1 addresses Karl Marx and the problems created by capitalism, Chapter 2 covers Emile Durkheim and the crisis of morality, Chapter 3 deals with Max Weber and rationalization, and Chapter 4 considers Georg Simmel and the tragedy of culture. Part II shifts the focus to American social theorists, examining how they both managed to absorb and transform the European theorists that influenced them. It also explores the ways that these theorists were intent on linking theory to social reform. Chapter 5 covers the Chicago School and the promotion of social reform, while Chapter 6 turns to structural functionalism and requisites for and impediments to achieving social harmony. Part III focuses on the unrest of the 1960's beginning with Chapter 7. It documents the emergence of conflict theory, treating it as a predecessor to the later widespread influence exerted by neo-Marxian theory. Chapter 8 covers neoMarxist theory and its radical critique of late capitalism, while Chapter 9 takes up the introduction of feminism into sociology with the advent of feminist theory. Part IV deals with the 1970's and 1980's, an era that witnessed the retreat of theory into itself. In that vein, Chapter 10 traces the advent of metatheory. Part V focuses on the significance of contemporary developments in social theory in an era of intellectual fragmentation, examining in particular the view that claims we have entered a new historical epoch. Chapter 11 involves the postmodern challenge to an uncertain future. Chapter 12 underscores the idea that we are entering a society predicated on difference, while Chapter 13 focuses on the future of sociological theory. There are very few texts in the social theory market that explicitly address the history of sociology as a whole. We seek to fill that void. Related to this, we also believe that this book will find a place in the market because of the rising interest in the nascent subfield of the history of sociology. This can be illustrated by the recent formation of the history of sociology section in the American Sociological Association. Competition: While there are many academic monographs dealing with aspects of the history of social theory, there are, in fact, few student texts that explicitly deal with this topic. We believe that the most significant book on the market is Alex Callinicos’ Social Theory: A Historical Introduction (New York University Press, 1999). Callinicos does a superb job of tracing the importance of social power (especially economic, ideological, and political domination) for social theorists, but he does so from a decidedly Marxist framework. Our proposed project differs in that it is more ecumenical in its approach. A second important book is Steven Seidman’s Contested Knowledge: Social Theory in the Postmodern Era, 3rd edition (Blackwell Publishing, 2003). Seidman takes a historical approach, but he does not actually write a history of sociological theory. He is highly selective in his choice of the social and intellectual forces that he chooses to examine. In addition, his concern is not to address the issues concerning the historical continuities and discontinuities that we focus on, but rather to re-center sociology so that it might achieve a public voice extending beyond the discipline. Although we also address this issue, it does not constitute the core of this book. Third, Johan Heilbron’s The Rise of Social Theory (University of Minnesota Press, 1995) is also an important work that utilizes an historical approach. Heilbron’s book employs the work of Pierre Bourdieu to address the intellectual, national, and global forces that gave birth to sociology. Our text can be distinguished from Heibron’s in that we are not concerned solely with the “birth” of sociology, which makes ours a broader endeavor. Moreover, Heilbron’s audience was not undergraduate and graduate students, and the writing style reflects that fact. Manuscript Length and Specifications: We would like to write a concise book that can serve as a stand-alone or supplemental text. Even as a stand-alone text, we would assume that professors would want to assign some primary readings in order for students to become acquainted with theorists first hand. For this reason, we think it is a good idea to produce a book that is not too long. We are proposing that the final product will be a manuscript of about 500 double-spaced pages of text. This would result in a text of around 350 print pages. We would include a time line and would like to consider the possibility of using some photographs. Schedule: Given the division of labor that the authors envision, we believe that the first draft of the manuscript could be completed 18 months after the signing of a contract. Attachment A THE DEVELOPMENT OF AMERICAN SOCIAL THEORY: THINKING THROUGH THE HISTORICAL TRANSFORMATIONS OF MODERN SOCIETIES TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction: An Overview of the History of Theory Identifying the central theme of this text, the chapter depicts theoretical development as a response to the social conditions of a particular time and place. But the chapter also acknowledges that theory encompasses what George Ritzer has called the “centrally important issues that have stood the test of time,” that theory is not only relevant to specific historical moments, but that the most important theories remain relevant long after they were formulated. We will briefly introduce each of the major traditions that we are going to discuss in the text, situating them in a general historical overview in order to illustrate why these theorists concentrated on the things they did in the ways they did. Although the focus of the book is on American social theory, we begin with the European classics because they shaped subsequent developments in the United States far more profoundly than did early American sociologists such as William Graham Sumner and Lester Ward. In the subsequent sections of the book, we reveal the European imprint on American sociology. The key point of this chapter is to demonstrate that theory does have a purpose, which is to open up ways of comprehending aspects of the social world. To this end, rather than dispensing with the “old dead white guys” that were so crucial to the discipline’s development, we seek to connect their contributions to the in many ways dramatically different social world we inhabit. Part I: The Founding Figures of Sociology in the Context of Their Times Chapter 1: Karl Marx and the Problems of Capitalism Chapter 1 focuses on Marx’s preoccupation with the negative impacts of capitalism on workers in particular and on social life in general. We address the initial problems created by the Industrial Revolution (poverty, child labor, length of the work day, demographic issues, various health concerns, etc.) and how Marx’s concentration on the proletariat as both victim and as agent of change originated from a concern about these social problems. We discuss how the wage system contributed to the reification of social class and how reification relates to alienation and false consciousness, thereby perpetuating the oppression of the working class. We also illustrate how the French Revolution and its commitment to democracy informed Marx’s theory, resulting in his belief that a socialist society would be democratic. Chapter 2: Emile Durkheim and the Crisis of Moral Order Chapter 2 stresses the importance of morality as a social problem for Durkheim. We address the importance of the French Revolution and its after effects in France, and the crisis of liberalism (in the form of both conservative and radical political factions) during this period. We also discuss the impact of industrialization, the decline of laissez-faire policies, and the rise of working class movements on Durkheim’s theories. In this social context, it is not surprising that Durkheim would focus on social reform as a way of achieving once again social stability, which he depicts in terms of the progressive movement from mechanical to organic solidarity. We will emphasize the importance of dynamic density in this process as well as the role Durkheim attributes to rapid social change. As the world becomes more individualistic, and in fact a “cult of the individual” emerged, Durkheim is concerned about promoting solidarity in order to avert a pathological anomic society. In this regard, we will examine his understanding of the distinctive role that sociology could play in furthering this goal. Chapter 3: Max Weber and Rationality Chapter 3 focuses on Weber’s interest in the rise of capitalism as one of the key manifestations of the triumph of formal rationality in the West. As part of this discussion, we explore the Protestant ethic thesis, seeking to clarify what its significance was for Weber’s theory of rationalization. We trace the importance of Germany’s social climate (especially the tension existing between traditional politics and modern capitalism) to Weber’s preoccupation with this development. We focus on the important political conditions of the day, including the negative impact of the Prussian Junker class, the concurrent rise of modern industrialism, the uniqueness of this coexistence. We explore Weber’s desire for the rise of a strong nation state and a successful capitalist economy, and his often pessimistic view about whether both could be achieved in Germany—or for that matter, elsewhere. Chapter 4: Georg Simmel and the Tragedy of Culture Georg Simmel was a contemporary of Weber whose work can serve as an interesting counterpoint since they confronted the same nation at the same time, but from significantly different social locations. As a Jew in Germany, Simmel was the victim of anti-Semitism and it took a toll on his academic career. Whereas Weber was always in the centers of the intellectual power elite in Germany, Simmel was marginalized. Often seen as an essayist with a perceptive, but fragmented contribution to social theory, we will examine The Philosophy of Money, which can be seen as his magnum opus, along with some of the most suggestive of his essays, such as “The Metropolis and Mental Life” and “The Stranger.” We will indicate how his belief that contemporary society was “cold” reflected his social location, and will highlight how he came to structure his social though in terms of the tragedy of culture. Part II: The Rise of American Social Thought Chapter 5: The Chicago School and Social Reform Beginning with Chapter 5 we shift our focus from individual European theorists to various schools of American social thought and the important theorists within these traditions. We discuss the advent of sociology in America after the Civil War and the closing of the frontier, concentrating particularly on the significance of the Progressive Period and the impact of rapid social change (industrialization, urbanization, immigration, etc.). Within this milieu, sociology in the United States emerged and very quickly the Chicago School of Sociology became the dominant voice in the new profession. In this chapter, we concentrate on the contributions to theory of its key voices, W.I. Thomas and Robert Park. Not only will we indicate that they made significant contributions to theory (and not simply to developing an agenda for research), but that they were deeply involved with social reform efforts. Thus, the theoretical relevance of American pragmatism to the Chicago School as well as the impact of social reform associated in particular with Jane Addams and Hull House will be analyzed. The Chicago School’s collective contribution to social theory will be view in terms of its reformist impulses, which sought to find an alternative to both the conservatism of Social Darwinism and to the radicalism of Marxists. Chapter 6: Structural-Functionalism and the Quest for Social Harmony and Inclusion In Chapter 6 we discuss the rise of structural-functionalism as a response to the major developments of the first half of the twentieth century, including the impact of the Russian revolution, the Depression, the New Deal, the rise and fall of Fascism, World War II, and the Cold War. Within this broad framework, we depict this new theoretical tradition, particularly in the work of its major proponent, Talcott Parsons, as a sophisticated, complex, and flawed defense of liberal democracy. Parsons produced a cadre of scholars that dominated social theory for a generation. As part of our review of this important school of thought, we will look at the contributions of some of his distinguished students, particularly the work of Robert Merton. Part III. The Unrest of the 1960's and the “Coming Crisis of Sociology” Chapter 7: Conflict Theory as a Transition to Neo-Marxian Theory We trace the decline of structural-functional theories during the tumultuous times of the 1960s, when the combined impact of the civil rights movement, the anti-Vietnam war movement, and the youth counterculture produced a crisis of legitimacy. In this context, critics of structural-functionalism argued that because of its emphasis on social order, it was not up to the task of helping to make sense of patterns of change. During this period, conflict theory emerged as what was perceived to be the inherent conservatism of the Parsonian legacy. While conflict theory made little lasting theoretical contributions to sociology, it was most important for laying the groundwork for more influential NeoMarxian theories. We will discuss, in particular, the work of Lewis Coser, Ralf Dahendorf, and Randall Collins. Chapter 8: Neo-Marxian Theory and Radical Critique Chapter 8 addresses how the acceptance of Neo-Marxian theory occurred in a political climate and within the structure of an American university system that was favorable to such anti-establishment ideas. We focus specifically on pivotal social issues such as baby boomers attending college in historic numbers, and federal and state agencies allotting funds to universities in unprecedented sums. We also stress social conditions such as the activist campus environment and the tenuring of New Left scholars, thereby defining a generational reaction to the quiescence of the preceding generation. We begin with C. Wright Mills’ attempt as a non-Marxist sympathetic to Marx’s ideas to bring Marxian theory into the mainstream. The chapter will focus in particular on elements of his work concerned with threats to democracy. We then turn to important Neo-Marxian theorists of the day, including Paul Baran, Paul Sweezy and Harry Braverman. We also examine the “discovery” of Critical Theory and its subsequent impact on American sociology due in large part to the fact that figures from the Frankfurt School such as Theodor Adorno, Max Horkheimer, and Herbert Marcuse lived as exiles in the U.S., permanently in the case of Marcuse, who played a role as theoretical “guru” for the New Left. Chapter 9: Feminism and Feminist Theory Although the earliest manifestations of feminist theory emerged early in the twentieth century, it really came into its own in the late 1960s. In this chapter, we trace the importance of liberal feminism, which has had the longest history and the broadest impact on American life. As illustrative of liberal feminism, we discuss the work of Jessie Bernard, Betty Friedan, Alice Rossi, and Rosabeth Moss Kanter. Liberal feminism laid the foundation for later feminist theories, which both build upon and were critical of its position, such as radical feminism (Catherine MacKinnon), psychoanalytic feminism (Nancy J. Chodorow), standpoint feminism (Donna Haraway) and multicultural feminism (Patricia Hill Collins). Part IV. Theory as Self-Conscious Enterprise: The 1970's-1980's Chapter 10: The Advent of Metatheory Chapter 9 briefly reiterates the importance of the 1960's for the development of sociological theory, moving into the dramatic changes that occurred within the field in the mid-1970's through the late 1980's. We argue that the result was a more introspective sociology. Nowhere was this more evident than in the increased focus on metatheoretical debates. We discuss the impact of Thomas Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions on the development of metatheory. We document George Ritzer’s call for a multi-paradigmatic sociology, Jeffrey Alexander’s multi-dimensional sociology, and James Coleman’s micro-macro model as efforts to reframe the sociological enterprise. Part V: A Cacophony of Competing Theories Chapter 11: The Post-Modern Challenge to an Uncertain Future While postmodernism originated as a European, philosophical project, it has had an enormous impact on American sociological theory. Chapter 11 offers two explanations for this ascent: one encompasses the field of sociology itself, while the other addresses more general societal events. Looking at sociology first, we argue that younger theorists embraced the postmodern critique primarily as a reaction to metatheory and the failure and unanticipated consequences of traditional grand narratives. Despite its promise, metatheory typically focused on texts and discourses, adding little coherence to the field of sociological theory. Instead, there appeared to be an endless, aimless, irrelevant theorizing about theories by one camp, while another camp fervently criticized these endeavors. For these younger theorists, the postmodern critique challenged the basic goals of sociology, and its power and epistemic privilege. At the societal level, we argue that openness to the postmodern critique can be traced to a variety of events that led many citizens to feel uncertain about both the future and our ability to rectify the most significant of social problems. We discuss some of the major theories of postmodernism including those of Jean Baudrilliard, Michel Foucault, and Jean Lyotard, and examine the extent to which they shaped developments in American social thought. Chapter 12: Entering a Fragmented Field By the 1980s there was no hegemonic theoretical school and few prospects that one would emerge. Instead, one heard voices of concern about the fragmentation of social theory. The reasons for this concern are obvious as one notes the proliferation of new theoretical schools that make little effort to speak to other perspectives. During this period, we have witnessed the emergence of queer theory, identity politics, standpoint theory, Afrocentric theory, and post-colonial theory. Moreover, theorists have conceptualized new stances that are intended to capture distinctive elements of contemporary society, such as Ulrich Beck’s “risk society”, Anthony Giddens’ structuration theory, Immanuel Wallerstein’s world-systems theory, and Jurgen Habermas’ theory of late capitalism. Some of these theories revel in the fragmentation of social theory, while others seeks to overcome it. We examine those forces—increasingly global in nature—working for and against fragmentation. Chapter 13: The Future of Sociological Theory Our concluding chapter reiterates the importance of various historical contexts on theory development. We make the argument that because the state of society is in constant flux, there is a need for sociologists to become social critics and public intellectuals. We argue that academic sociology must reward this activity; we must follow in the footsteps of the “masters” and re-engage ourselves in the public debate. It is also time for the field of sociological theory to acknowledge the importance that social context has on our theorizing. We argue that to better understand what social theory’s potential is in the future, we need to understand where we have been.